Design ‘misconstrued as decoration’

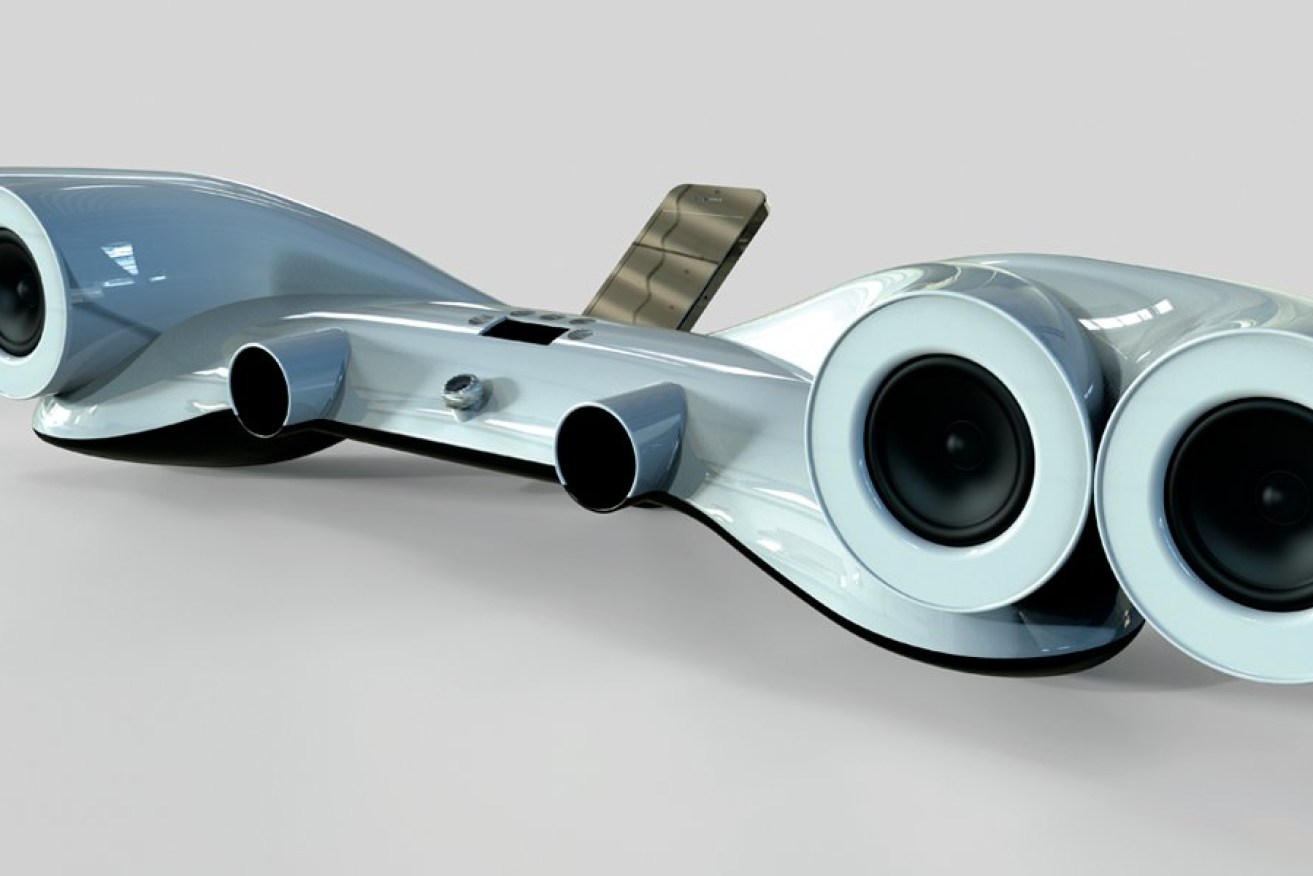

Luigi Colani iPod Dock. Photo: Andrew McIntyre

Paola Antonelli, a senior curator and director of research and development at New York’sMuseum of Modern Art (MoMA), caused a minor art world storm when she added videogames to the official collection of one of world’s top art museums.

As well as acquiring Tetris and Pac-Man for the MoMA collection, Italian-born Antonelli has included the @ symbol and the Google map pin drop symbol as examples of iconic design.

In her view, design is as much about interaction and behaviour as it is about artefacts.

In this edited Q+A with Professor Anthony Burke, Head of the School of Architecture at the University of Technology Sydney, Antonelli explains why design is much more than just pretty objects and Scandinavian furniture.

Anthony Burke: Why is design so special to you?

Paola Antonelli: I studied architecture but it was not my mission.

[Design is] one of the highest expressions of human creativity. I always say that designers almost take a Hippocratic oath. An artist can choose whether to be responsible towards other human beings or not, but instead a designer has to be, by definition.

Without designers, life would not happen because any kind of scientific or technological innovation gets filtered by design and becomes part of our life. Without designers, we couldn’t use microwaves, we couldn’t use the internet, we couldn’t use so many innovations.

Burke: But most people think design is nice furniture from Scandinavia.

Antonelli: They think about it as an embellishment. I mean, it kills me. My job is to make people understand that it is so much more.

Burke: Design has had a bit of a renaissance, almost; it’s come back into people’s lives in a broad way. Why do you think that has happened recently?

Antonelli: In the United States, where I have been living for the past 20 years, design has been kind of neglected or misconstrued as decoration or as an embellishment for a really long time.

Lately, it’s been reconsidered and I have to say, it’s mostly because of [the late Apple CEO] Steve Jobs. The funny thing is that that’s a blessing and a curse at the same time. It’s a blessing because Apple indeed did a lot to elevate the threshold of popular acceptance of design quality so people have started demanding more.

Apple set the bar higher. It’s a curse because this kind of perfection that Jobs was advocating is not easy to achieve and should not be the paragon for design.

Also, it concentrates the attention again on objects; [whereas] it’s so important to make people understand that interfaces, the ATM machine, and the interface of your phone, visualisation design, that they’re such important parts of our time.

Burke: Normally we think of design within the creative arts and architecture but I think business now is interested, economists are talking about design, research and development departments of big companies now have design thinking units. Why is that?

Antonelli: Design thinking is not design. Design thinking is to design what the scientific method is to science. It’s the steps without the knowledge and the years of training. And design thinking is a real danger because many companies think they’re doing design and they’re not.

So it’s become a real consultant’s playground, and a way for many companies to abdicate their responsibilities towards design. It’s really a big problem.

If you only deal with the process without any education beforehand, you’re discounting the idea of design, [saying it is] something you don’t have to go to school to learn.

It’s impossible to define what is design. You know, it’s like trying to define what art is. It’s everything that we make, if you wish. And some of it is good, and some of it is bad.

Burke: You have spoken in the past about interaction design. Can you tell us about that?

Antonelli: Interaction design is the design of the behaviour between a person and a machine. I always use the ATM machine as an example, because some ATM machines are disasters and some of them are good. But you can feel the care and the work that goes into the design of the interface.

I decided to start acquiring videogames for the Museum of Modern Art because they really focus on this idea of interaction design and on behaviours. So they almost are pure because there is no function. In some cases, they can be educational, but in most cases it’s just about exciting a certain kind of behaviour in you that is about letting go.

Burke: What else are you working on at the moment?

Antonelli: For the collection, we have been acquiring videogames and certain crucial icons. Two years ago we acquired the @ sign, and about a month ago, we acquired the Google pin, you know from the Google maps. And we’re acquiring more and more typefaces and fonts.

I’m also working on a curatorial experiment online that is called Design And Violence that explores the contemporary manifestations of violence in society by looking at objects that have an ambiguous relationship with it.

For instance, there are the green bullets that are developed by the US Army that are lead-free bullets. So they will still kill you, but they will not harm the environment.

So what we do is we take these objects and we have experts that have written about violence, like cognitive scientists. They write about these objects, then we post it online and have a conversation happening with the public.

One of the goals [of our research and development] is to really make sure that museums make sense in the future. Especially museums like MoMA that are completely private. We don’t receive any money from the government so we have to be self-sustaining; we have to keep ourselves relevant.

Burke: With this turn to interaction design and those more electronic forms of design, what happens to the more traditional forms of design like Scandinavian furniture?

Antonelli: You really are touching a sore spot. It’s almost as though I’m talking about a lover, but furniture ceased to satisfy me a long time ago. I probably see one or two pieces of furniture a year that I am flabbergasted by. I don’t think it has only to do with me being jaded, although I don’t discount that.

I think we have become a little wary about objects. We demand more from objects. We are also conscious of the fact that there’s too much stuff on Earth, so it better be really worthwhile. I think it is healthy because the fewer objects the better, in a way.

There’s also a whole universe in the fifth dimension online that is for designers to explore. We know the Second Life platform didn’t really succeed; it was too clunky and difficult.

But I am pretty sure that, in the future, we will have more and more virtual environments that will also have their own objects. Designers can work on those. This will also be an economy. There’s going to be this whole life we have online that is tied to the physical world but is also autonomous.

Burke: What’s your current favourite piece of design?

Antonelli: Well, there’s a new variation of the handicapped sign, the wheelchair sign, that I love that we just acquired into the collection.

The old one had the static person in the wheelchair waiting to be pushed. The new one, it’s almost like the Paralympics, they are jolted forward, they don’t need anybody, it’s going. I like that. It made me excited.

I think it’s our job as curators to present great checklists of fabulous objects.

When we can have them physically or digitally and preserve them, it behoves us to do so. In the case of the @ sign, it’s in the ether but it’s still part of my job to indicate it as an example of great design. So we just put it on the wall.

We chose American Typewriter as the font because that’s the font that Ray Tomlinson used in 1971 when he was working for the agency that was commissioned by the US government to design email.

He found the symbol that was used by accountants that had existed since the Middle Ages. He did some research, he understood that this symbol meant “in relationship with”. He adopted it to collapse all the lines of code that connected the person to the machine, in the email address.

Artefacts in the digital realm are alive. You can’t put them in a cage.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.