Dickensian twists and the war on whistleblowers

Contrasting sessions exploring the ingenuity and audacity of Dickens and Australia’s treatment of high-profile whistleblowers were among highlights on day three of Adelaide Writers’ Week.

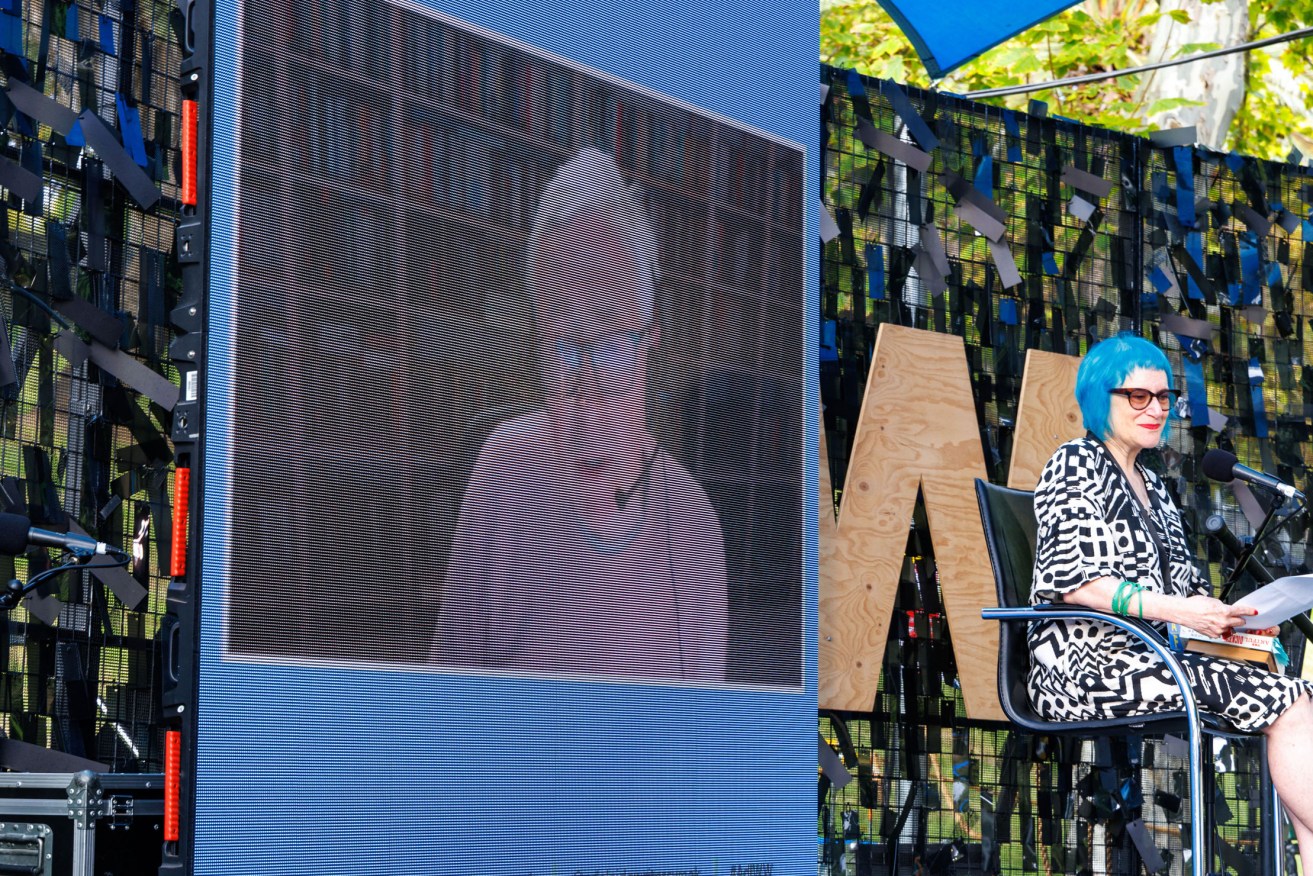

Novelist Linda Jaivin chairs The Art of Dickens session with John Mullan, who appeared at Writers' Week via video link from the UK. Photo: Tony Lewis / InReview

A session of pure literary fun opened Monday at Writers’ Week, despite Charles Dickens expert John Mullan initially missing from a UK video link, leaving novelist Linda Jaivin flying solo on the main stage at the Pioneer Women’s Memorial Garden.

Jaivin, a China expert who is also a Dickens fan, held the floor before Mullan appeared, converting her research into an impromptu chat about Dickens and Mullan’s book, The Artful Dickens, whose chapters include one on the use of smell as a plot device and another on characters who drowned.

“Dickens is hilarious, Dickens is such high comedy, even when he’s writing tragedy, and he pulls it off,” Jaivin said.

An apologetic Mullan, once present, said Dickens was condescended to in his lifetime by critics. They would acknowledge that yes, of course he was very funny, or agree that he was popular and sold a lot of books, but his cleverness was missed then – and also sometimes now. Barely anyone noticed that Bleak House seamlessly interleaved chapters that switched between the past and the present tense, and between first and third person, while building a vast story.

“Nobody had ever done anything like this in novels before; it’s the kind of thing you might do nowadays if you wanted to get onto the Booker Prize longlist, to show how ingenious you are,” Mullan said. “It’s almost as if some of his experiments were so unusual, they were invisible.”

The strong moral thread in Dickens’ novels tended to remain embodied in characters who represented a certain trait, like the unctuous Uriah Heep or miserly Ebenezer Scrooge, rather than being incorporated into stories which had a moral point. Unlike Thackery or George Eliot, Dickens, who was a famously bad husband and father, did not set out to preach.

“He is not a writer that one goes to, to find out wisdom about how one should live one’s life,” Mullan said. “I think he tells us about the monsters in our own head, in a way. He is not a wise and didactic writer at all.”

He was also a writer unafraid of cliché or coincidence, and almost relished creating absurd connections, just to make a point. Mullan gave the example of David Copperfield, who visits a model prison with a reputation for rehabilitation, only to be presented with the familiar fraudster Uriah Heep, the “oleaginous hypocrite” who was now the prison’s model penitent.

“There is one kind of reader of this who says, ‘Oh, this is impossible. How can this happen?’ but the Dickens reader doesn’t say that, the Dickens reader goes, ‘Of course!’,” Mullan said.

“It’s not just the connections that he makes but the audacity with which he uses the things which novelists are told they shouldn’t do. The sins of bad writing he turns into creative devices.”

———–

War on Whistleblowers chair Andrew Fowler with Bernard Collaery and David McBride. Photo: Tony Lewis

You don’t become a whistleblower if you want success, you become a whistleblower because you are so angry you have no choice. Former army lawyer and soldier David McBride, recently re-admitted to law practice in New South Wales, told a supportive afternoon audience this was why he felt compelled to provide the ABC with evidence about alleged war crimes by Australian troops in Afghanistan. As a consequence, he was charged under the Defence Act, lost his house and for a time his career.

“I wanted to stand up and be counted, that’s all,” said McBride, who did two tours in Afghanistan and loved his job as an army lawyer. “Obviously it comes with a cost… but at the end of the day, you don’t work for the government, you don’t work for the pay rise; you work for the principle. I worked for the idea of Australia, not the government of Australia.”

With detailed allegations of Afghanistan war crimes now being aired almost daily without consequence in the defamation trial brought by Australian VC holder Ben Roberts-Smith, McBride accused the Federal Government of not really caring about the law, only wielding it to put enemies in jail.

“It’s not applied consistently,” McBride said. “And if it’s not applied consistency, it’s not a law, it’s a government weapon.”

On the stage with McBride at the War on Whistleblowers session was Bernard Collaery, former Northern Territory attorney-general and legal adviser to Timor-Leste who was charged over his alleged role in revealing Australia spied on the East Timorese delegation during 2004 negotiations over a seabed oil and gas treaty.

When Collaery brought action under international law against the Australian Government, arguing the bugging nullified the oil and gas treaty, he was raided by ASIO. He is still being prosecuted.

The case has become so absurd the Government is fighting to try him in secret so it will not have to admit the spying took place.

“They want to put me to trial over something that they want to publicly deny, and are publicly denying,” Collaery said. “They want a secret trial because to try me, they have to admit what was done.”

Australian human rights lawyer and former Rhodes Scholar Jennifer Robinson, speaking from London where she defends WikiLeaks’ Julian Assange, said she did not want to live in a democracy where good men like McBride and Collaery were on trial for doing what was right and in the public interest.

“I don’t want to live in a democracy where a lawyer who is doing his job is prosecuted – that is a terrifying precedent,” Robinson said.

She said Assange was targeted so heavily by the US after releasing intelligence leaks (which included a video of US military shooting Iraqi civilians from a helicopter) because “information is power”. The US was still fighting to jail Assange more than a decade later in order to deter anyone else from publishing the truth, she said.

“A journalist and editor with information was suddenly seen as the most powerful man in the world, or the most dangerous man in the world, and why? Because he was offering us the truth,” Robinson said. “The truth about war crimes, the truth about human rights abuses.”

Robinson said assurances from the US that Assange, a clear suicide risk, would be safe in a US prison were not accepted.

“It is not a full assurance and it is not worth the paper it is written on, in my view,” she said.

Audiences on day three of Adelaide Writers’ Week in the Pioneer Women’s Memorial Garden. Photo: Tony Lewis

Adelaide Writers’ Week continues in the Pioneer Women’s Memorial Garden until Thursday. InReview will be reporting from Writers’ Week each day. Click here to read coverage of other sessions.