Diary of a Publisher: What is truth?

There’s been a revival of interest in George Orwell’s 1984 in the past few years, and a recent reading of the novel has seen it get under the skin of publisher Michael Bollen.

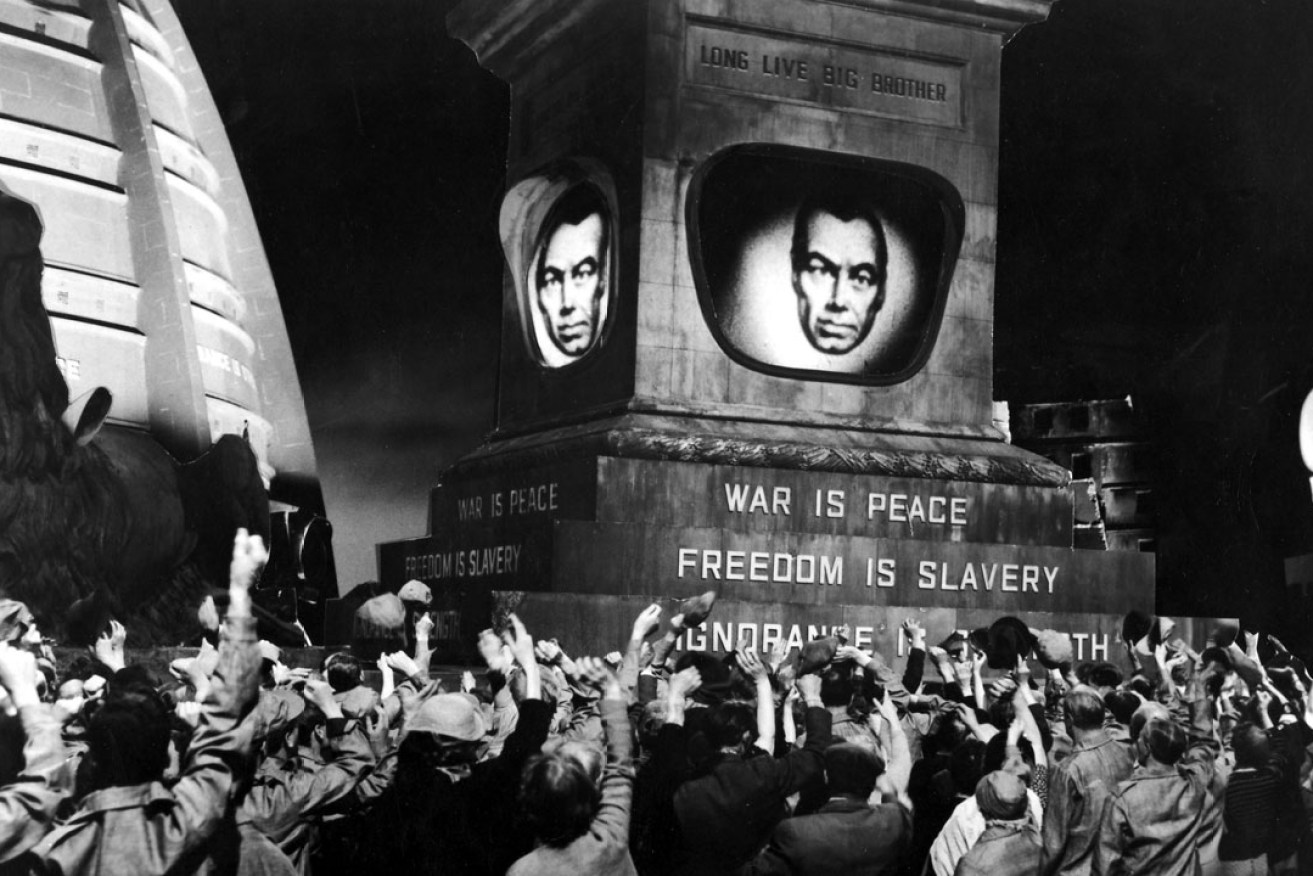

Big Brother is watching: A scene from the 1956 film adaptation of 1984. Photo: Mary Evans Picture Library

I’ve just finished reading George Orwell’s 1984, which was lying in the pile by my bed. I supposed I’d read it before – would say I have if asked – but I didn’t recognise much of it. Fitting, I guess, since a major theme is the elimination of history and memory, and their replacement, in today’s phrase, by “alternative facts”.

What is truth?, as Johnny Cash sang.

As books can, this one has got under my skin. You know how you start seeing your day through the prism of a story you’ve heard, or how a word you’ve encountered becomes suddenly part of everyday talk, or a person starts bobbing up everywhere after you’ve first met?

My daily life is publishing books, a regular monthly list of them. And so I start pondering our new releases through 1984 glasses.

From the title of Jon Jureidini’s and Leemon McHenry’s The Illusion of Evidence-Based Medicine, you might think this is a kind of anti-empirical-science tract. Quite the contrary. The authors come out blasting at the start:

From the title of Jon Jureidini’s and Leemon McHenry’s The Illusion of Evidence-Based Medicine, you might think this is a kind of anti-empirical-science tract. Quite the contrary. The authors come out blasting at the start:

“Doctors and patients are misled by claims that appear to be grounded in the authority of science, but in realityare little more than marketing. Instead of treating real diseases with essential medicines, pharmaceutical companies persuade doctors to prescribe drugs for conditions in which the harm/benefit analysis does not favour the treatment. Even in the case of potentially life-saving drugs, the true harms and benefits that emerge during scientific testing or subsequently are often concealed by those who have a financial interest in the outcome.

“In this book, we expose the corruption of medicine by the pharmaceutical industry. At stake is the integrity of one of the greatest achievements of modern science –evidence-based medicine.”

The phrase “Big Pharma”, of course, is a play on Orwell’s “Big Brother”. It’s telling that in Charlie Archbold’s fast-paced, dystopian novel for young (and old) adults, Indigo Owl:

The phrase “Big Pharma”, of course, is a play on Orwell’s “Big Brother”. It’s telling that in Charlie Archbold’s fast-paced, dystopian novel for young (and old) adults, Indigo Owl:

“As Earth was bleached and destroyed by climate change, only private corporations could afford to colonise space. Our planet, Galbraith, is named after what was once the biggest pharmaceutical enterprise on Earth.”

On Galbraith, the executives control citizens’ fertility by a compulsory sterilisation vaccination, Earth having been ravaged by population explosion. But what are the costs? Our young cadets discover a planet-wide conspiracy in this provocative adventure of the future drawn from the present and the past.

Emma Ashmere’s short stories in Dreams They Forgot take place very much on our earthly planet. But as the title suggests, and our cover line states, these are “stories of illusion, deception and quiet rebellion”, with Ashmere’s fiction working to explore and restore hidden layers of history.

In “The Historic Present”, a woman researching inspects today’s boxes of historical documents she’s ordered. The last box is:

In “The Historic Present”, a woman researching inspects today’s boxes of historical documents she’s ordered. The last box is:

“Newspaper clippings: Do not leave your dead on the hospital steps. And a minute book of the Hospital Auxiliary: It has been brought to the attention of … without visible means of support … cholera … three unidentified females found frozen to death … They were mistaken for heaps of rags.

“She blinks as she hurries down the State Library steps – hoping, fearing – she’ll find men in top hats and women in crinolines tiptoeing through the horses’ dust. By the time she’s threaded her way to the corner of Swanston and Lonsdale streets, she tells herself she’s already forgotten them.

“Why then, three heaps of rags huddled at her feet?”

Kirsten Coelho and Sera Waters, 2011, The Silence Surging Softly Backwards. Photo: Grant Hancock

Looking at ceramic artist Kirsten Coelho’s still and perfect vessels, they seem both of now and of other times.

“One outcome of a close acquaintance with Coelho’s remarkable practice (and its referents),” writes Wendy Walker in Kirsten Coelho, “is an enhanced attentiveness to the latent beauty to be found in forms not merely overlooked, but arbitrarily discarded. An especially shapely nineteenth-century salad-dressing bottle – discovered at her local Port Adelaide market – is recognisable as the prototype for the sinuous form of an elegant bottle . . .”.

I’m taken with an image from a 2011 collaborative installation by Coehlo and craft artist Sera Waters, The Silent Surging Softly Backwards. As Walker relates, this was a work where fiction, history and visual art meet, with the installation inspired by Katharine Susannah Prichard’s Australian Gothic story The Curse (1932) and a scene from the 2005 Australian film The Proposition. “This glimpse of (delusional) cosy domesticity represents a moment of calm ruptured by the unleashing of terrible violence.”

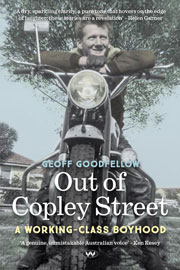

Invincible poet Geoff Goodfellow has re-created himself as a writer of prose memoir in Out of Copley Street: A Working-Class Boyhood. With a poet’s ear, he never wastes a word. His yarns have “a dry sparkling clarity”, Helen Garner writes, “a pure tone that hovers on the edge of laughter”.

Invincible poet Geoff Goodfellow has re-created himself as a writer of prose memoir in Out of Copley Street: A Working-Class Boyhood. With a poet’s ear, he never wastes a word. His yarns have “a dry sparkling clarity”, Helen Garner writes, “a pure tone that hovers on the edge of laughter”.

Many years ago, Goodfellow showed me a version of his first short piece, then (if memory serves, which seems unlikely) called “Persistence pays dividends”, now the cheerier “Bluey gets a start”. Difficult not to smile along as Geoff, aged “nearly five and a half”, works his job as assistant to Lenny the milkie:

“After another five houses, we turned right into Watson Avenue, having finished the round. Lenny looked over and asked if I’d like to take the reins. I jumped at the chance and stood erect on the platform of the milk cart, looking out and over the backside of the harnessed horse. I clutched the fat encrusted leather in my little pink hands and felt like a winner again. I gave the reins a light slap, enough to fasten the pace without hurting the horse, and then turned to Lenny, urging him to yodel. He’d done it a couple of times before and I loved the unusual sounds he could make. I’d heard others yodel on the wireless but Lenny was the only person I knew who could do it in real life. He didn’t disappoint me either and kept it up until we’d almost turned into Copley Street.”

Makes me want to yodel, but I’m not sure how. Will practise in the park, not the office.

I am just old enough to remember the clip-clop of the milkman’s cart passing by our suburban home, running out to look. Or was it the baker’s cart? Maybe the milkie was gone by then, at least in his horse-drawn iteration.

I know for sure, however, our family somehow scored a baker’s cart when the horses disappeared. It was covered, enclosed like a van, and we’d play in and on top of it. Across the fence we could snatch ripe sweet locquats, which I always want to spell locusts, from the neighbour’s tree. Their stones, good for throwing at those folk stuck on the ground, were smooth and so shiny you could, in imagination at least, see your reflection in them.

That seems real to me.

Michael Bollen is director at Adelaide-based independent publishing house Wakefield Press. He writes a regular column for InDaily.

Read SALIFE’s recent interview with Geoff Goodfellow here, and an extract from Emma Ashmere’s Dreams They Forgot here.