An incredible story of survival in Fierce Country

How could an ill-prepared American stay alive for 43 nights in the Australian desert with only tea brewed from gum leaves, native berries and murky water to survive on? Adelaide author Stephen Orr recounts Robert Bogucki’s strange tale in his new book of ‘true stories from Australia’s unsettled heart’.

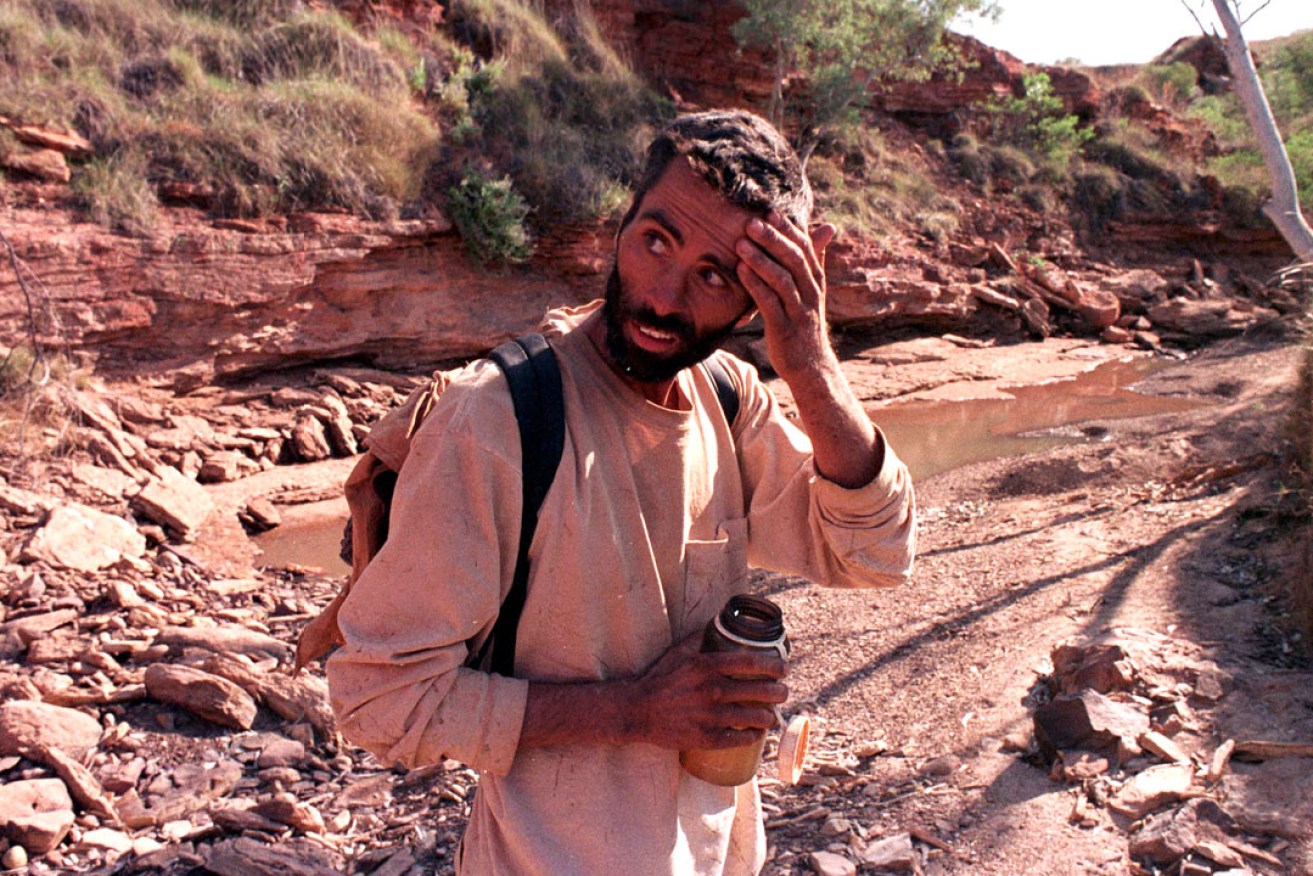

Robert Bogucki near the water hole where he was found. Photo: Robert Duncan / AAP

The Fierce Country transports readers to what are described as the “open spaces and isolated places” outside our cities. Its 19 true stories – which date from 1830 to today – are all said to have had an impact on the Australian psyche, and include mysteries, disappearances, mistreatment and murder.

This extract, from Chapter 16, tells of an American fireman who set out on an ill-advised outback adventure that led to a huge land and sea search – and even a rescue mission from the US led by a cigar-smoking, larger-than-life character known as “Gunslinger”.

After six weeks wandering alone in WA’s Great Sandy Desert with no supplies, how could he possibly still be alive?

Robert Bogucki

1999

43 nights in the desert – Riding around Australia – Sandfire Roadhouse – Wandering the desert – Ray and Betty become worried – Gunslinger arrives – Murray Gavey succumbs to the heat – Bogucki is found! – ‘scratched the itch’ – Robert Duncan has his own wait – Evan Muncie and the man dressed in white

When he was a troubled 15-year-old, Alaskan Robert Bogucki decided one day he would, like Jesus, head into the wild – to test his faith, to explore his relationship with God. It would be another 18 years before Bogucki got the chance to experience his 40 days and 40 nights in the desert (in his case, 43); to have his questions answered. And when it was all over, the searches concluded, the newspaper articles written, he said, ‘It’s still going through my mind the things I’ve seen and experienced. I feel satisfied that I stretched that edge, whatever it was that sent me out there in the first place. The only feeling I have right now is a feeling of confidence that God will take care of me.’

In 1999, 33-year-old Bogucki took time off from his job as a fireman in Fairbanks, Alaska, to ride a bike around Australia. Somewhere along the way, as he travelled from Perth up the west coast along the Great Northern Highway, he saw a map showing Australia’s second biggest desert, the Great Sandy Desert, an area of nearly 300,000 square kilometres, surrounded by the Pilbara and southern Kimberley regions, and the Gibson and Tanami deserts. With its nine-month summer, feral camels and endless spinifex grass, this seemed just the place to lose yourself, for better X CHAPTER 16 Robert Bogucki 1999 169 Robert Bogucki or worse. At last, he knew the time had arrived. Throwing aside all common sense, he decided where his bicycle journey would take him next.

After a long, hot ride, Bogucki arrived at the Sandfire Roadhouse, 1910 kilometres north of Perth. He avoided telling anyone about his plans. Later he explained he’d decided to ride across the Great Sandy Desert to Fitzroy Crossing, a small town approximately 500 kilometres from the roadhouse. After his rescue he said, ‘I wanted to spend a while on my own with nobody else around, to make peace with God.’

Bogucki set off on his odyssey on 11 July 1999. He didn’t have enough food or water for the long journey through one of Australia’s harshest landscapes. Common sense must have told him he had almost no chance of completing his trek. Daytime temperatures in the desert are some of the hottest in Australia and there are few permanent water sources. Apart from goannas, kangaroos, bilbies and marsupial moles (not that Bogucki had the skills to catch them) there was nothing to eat. Later, police would be at a loss to understand his actions. Superintendent Steve Roast, from the Broome police, summed up most people’s views of the American. ‘We have to face the facts. Mr Bogucki went out there alone. It was an extremely irresponsible thing for him to do.’

Bogucki’s parents, Ray and Betty, received a postcard at their Miami home from their son on 20 July and assumed all was well. But it wasn’t. By then Bogucki had been wandering the desert for nine days. He later admitted he had run out of food a few days into his trek and had survived by eating small native plants. Then, on 26 July, tourists found his camping gear and bike abandoned several kilometres along the east–west aligned Pegasus Track, a ‘line’, or mining survey track, put down by Pegasus Metals, leading into the Great Sandy Desert.

The next day, 27 July, a land and air search for the missing trekker got underway. Police planes, four-wheel drives and Aboriginal trackers tried to ascertain his position. A combination of soft sand and dense scrub made it difficult for searchers to 170 The Fierce Country follow his tracks. The operation continued for 12 days, at which time police, believing he’d either hitched a ride out of the area or perished, called off the search.

Ray and Betty Bogucki refused to accept their son was lost. They believed Robert had the skills and will to stay alive. They also thought he might be attempting to avoid discovery as part of his ‘quest’. They contacted the 1st Special Response Group (1SRG), a privately run emergency search and rescue organisation based at Moffett Field, California, and asked for help. 1SRG – its motto ‘Anytime, Anywhere’ – usually responded only to requests from ‘government agencies or recognised humanitarian, disaster relief, or search and rescue organisations’. But, after talking to Ray and Betty Bogucki, 1SRG realised it could help.

Within days of the request 1SRG was on its way to Australia. Over the coming few weeks this distinctly American organisation would irritate police, locals and searchers with its gung-ho methods and attitudes.

The group, led by cigar-smoking, larger-than-life figure Garrison St Clair (‘Gunslinger’), consisted of eight searchers and three dogs. Upon their arrival local police weren’t interested in helping. They were suspicious of these ‘cowboys’ who were unfamiliar with the desert. The last problem they needed was another eight missing persons, and another desert search. Likewise, car-hire firms in Broome wouldn’t rent the Americans a vehicle – several four-wheel drives had been damaged in the earlier search. Eventually the ever-determined St Clair managed to hire a tourist coach from a Broome hotel. Police concerns regarding ‘Gunslinger’ seemed vindicated when 1SRG bogged their vehicle just outside Broome and the local State Emergency Service was called to free them.

Also, by now, police were suspicious that Bogucki was deliberately evading them, either to test his survival skills, or because he had a US publishing deal in mind.

Bogucki had been in the desert for well over three weeks. Most 171 Robert Bogucki locals believed there was no chance he could still be alive. But he was, walking 15 to 30 kilometres per day, eating fruits and flowers from native bushes, drinking muddy water from creeks. This wasn’t the hottest time of year, but it was still punishing.

History suggested this was the case. Charles Wells and George Jones of the Calvert Expedition had perished close by just over a hundred years earlier, and lost jackaroos Simon Amos and James Annetts had suffered a similar fate only 12 years before. This country demanded respect and caution. Bogucki, the apparently level-headed fireman, had showed neither. Deep down, most believed this ‘new age Yank’ had it coming.

The warnings had been there. Murray Gavey had been working at Kununurra in the East Kimberley region of Western Australia. In 2004 Gavey attempted to cross the Great Sandy and Gibson deserts on a motorbike, setting out from Kununurra and heading south to the Aboriginal community of Yagga Yagga (400 kilometres south of Halls Creek) where he stopped for fuel. Once there, locals tried to dissuade him from continuing his journey, seeing how he was low on petrol – Yagga Yagga only stocked diesel – and the track he was travelling was rough and overgrown, avoided even by locals.

Like Bogucki, Gavey was determined. He left Yagga Yagga on 29 September with limited fuel and water supplies, heading for the small community of Kirwirkulla, 300 kilometres south. When, several days later, he failed to arrive, his wife reported him missing. A large land and air search commenced. Gavey’s body was eventually found inside his tent at a makeshift campsite. He had no fuel or water, and he’d been riding on a flat tyre for some time. A police spokesman said, ‘It’s pretty inhospitable out there – a lot of sand dunes, some of them 150 foot high, and very easy to get lost because of the number of little side tracks.’

‘Gunslinger’ St Clair eventually persuaded Western Australian police to help 1SRG in their search. The group set up a base camp on the edge of the Edgar Range, a series of hills and gorges 172 The Fierce Country approximately 200 kilometres south-east of Broome. St Clair believed this area, west of Geegully Creek, a tributary of the Fitzroy River, was the country Bogucki would have had to cross on his way to Fitzroy Crossing.

1SRG picked up from where the Aboriginal trackers had left off. They used a combination of searchers, dogs, and trackers in helicopters to accelerate their search, but three days later they had found nothing. Then, with the Americans on the verge of giving up and heading home, a media helicopter sighted some of Bogucki’s belongings abandoned on a blue tarpaulin. Along with a T-shirt, boxer shorts, empty water bottle, sunscreen, tent and Bible, searchers found a notebook containing confused, rambling thoughts. Broome police said, ‘They’re the thoughts of a bloke obviously in isolation. It goes all over the place.’

The following day, Monday 23 August 1999, after 43 days in the desert, and following 28 days of searching, Bogucki was found alive wandering gorges in the Edgar Range. A Perth Channel Nine news crew in a chartered helicopter made the discovery. In all, Bogucki had travelled 400 kilometres from the Sandfire Roadhouse. Although he was confused and disoriented, he was in good health. In an interview close to the creek in which he was found, Bogucki appeared surprised, but coherent. Watching the footage today it appears the Alaskan wasn’t truly aware how close he’d come to death.

The following day, Monday 23 August 1999, after 43 days in the desert, and following 28 days of searching, Bogucki was found alive wandering gorges in the Edgar Range. A Perth Channel Nine news crew in a chartered helicopter made the discovery. In all, Bogucki had travelled 400 kilometres from the Sandfire Roadhouse. Although he was confused and disoriented, he was in good health. In an interview close to the creek in which he was found, Bogucki appeared surprised, but coherent. Watching the footage today it appears the Alaskan wasn’t truly aware how close he’d come to death.

On hearing the news of Bogucki’s discovery, St Clair said, ‘I think he wanted to be found. He said he thought he was in trouble several days ago, so he lightened his load.’

Bogucki was flown to Broome, and admitted to the Broome Hospital, where medical staff said they couldn’t believe how good he looked. He’d lost 20 kg and had severe sunburn and blistering, but his only real injuries were scratches on his feet and back.

Bogucki told hospital staff he had ‘scratched the itch’ that had led him into the desert. He said, ‘I just wanted to spend a while on my own, just nobody else around, just make peace with God I guess.’ He promised never to repeat his odyssey, but police weren’t 173 Robert Bogucki happy, having invested large amounts of time and money in the search. Eventually, though, they declined to press charges.

When asked if he’d found ‘enlightenment’ Bogucki replied, ‘Before I started out I really didn’t know what I was looking for. I really felt alone, not desperate but just without hope at some point.’ From his hospital bed, he explained that, ‘I feel bad that a lot of people came looking for me, that there was so much spent in time and effort, and I really appreciate it …’

Western Australian Premier Richard Court wasn’t so understanding, insisting Bogucki pay for part of the search. ‘What he did was quite reckless. To set out on something, knowing that there would be a significant risk, not properly informing authorities as to what and how you were going to do …’

Which is the key to understanding Bogucki’s actions. Did he really have no idea what he was in for as he rode away from the Sandfire Roadhouse? Did he think God would lead him through the desert? Did he have a death wish or, as some asked afterwards, did he have a few roos loose in the top paddock?

Premier Court had made up his own mind. ‘I certainly hope that he and his family are prepared to pay for a significant part of the search, and I certainly wouldn’t like to see someone profiting from that sort of experience without making sure the bills were paid here.’

In the years since Bogucki’s odyssey the rumoured book has never appeared. Perhaps we need to take Bogucki at his word, and try to understand that this was just an ‘itch’ that needed scratching. Nonetheless, the scale of the American’s irresponsibility was breathtaking: the time wasted, the police resources tied up, the cost and efforts of State Emergency Service volunteers, not to mention Ray and Betty Bogucki, worried sick about their son.

But perhaps Bogucki’s disappearance was a re-affirmation, a reminder to all of us that life is precious. As the fireman later said, ‘There’s just been an amazing outpouring of concern, and I’m sorry that people had to go to so much trouble.’

Bogucki’s is one of the great survival stories. He stayed alive 174 The Fierce Country for six weeks on nothing more than tea brewed from gum leaves, native berries and murky water. Still, there are even more amazing survival stories.

On Tuesday 12 January 2010 a 7.0 magnitude earthquake hit the small Caribbean country of Haiti, with its epicentre approximately 25 kilometres west of the capital, Port-au-Prince. Hundreds of thousands of homes and businesses were destroyed and somewhere between 92,000 and 300,000 people killed, making this the sixth deadliest earthquake ever recorded.

On 7 February, 28 days after the quake, a 28-year-old man, Evan Muncie, was pulled from the rubble of an apartment building two weeks after authorities had called off the search for survivors, and 11 days after the last survivor had been rescued. Although he had lost 14 kilograms no one could believe he had survived so long without water. Muncie, later dubbed the ‘miracle of Haiti’, now holds the record for longest survival without an obvious water source.

When asked how he’d managed to survive, Muncie explained that he’d been given water by ‘a man dressed in white’.

Perhaps Bogucki, as he set off from the roadhouse, knew something we don’t.

This is an extract from The Fierce Country, by Stephen Orr, published this month by Wakefield Press. © Stephen Orr, 2018