Fractured memories: Quentin’s remarkable story

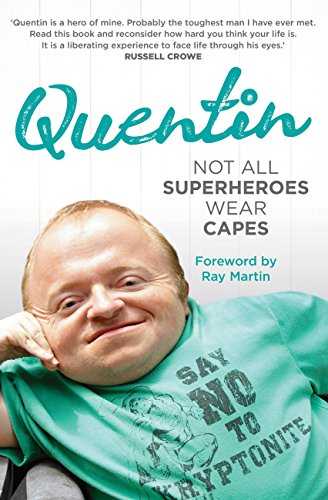

Not All Superheroes Wear Capes – Quentin Kenihan’s story of growing up with a rare bone disorder and being thrust into the public eye – is not “inspirational porn”.

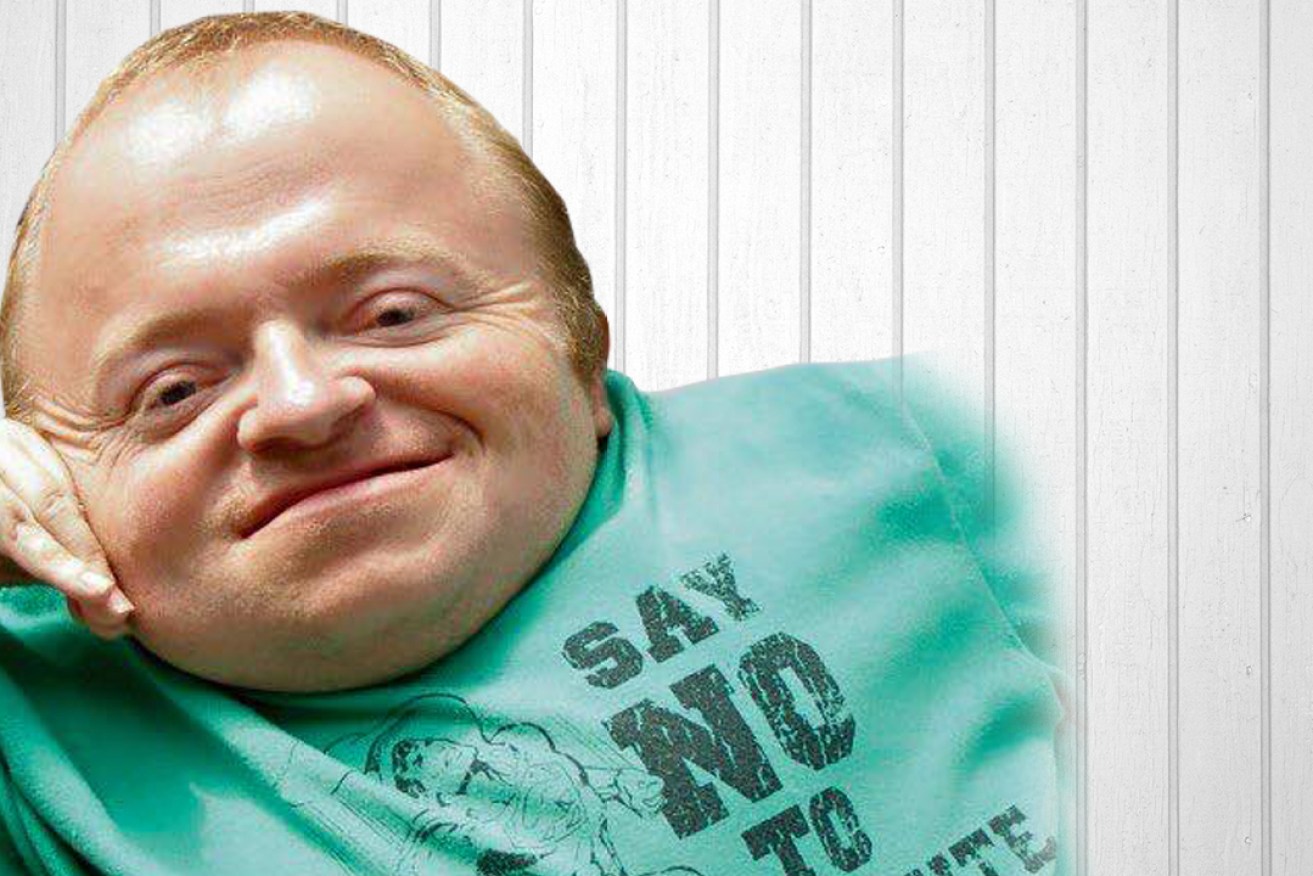

That’s Kenihan’s phrase, and one perhaps that could be said to have been the role he unwittingly played from the age of seven when he became a poster boy for disability. Who could resist his against-the-odds pluckiness and his cute little feller never-say-die irascible wit that stared down his condition – Osteogenesis imperfecta – that means his bones easily and constantly break?

But since then, Kenihan, now 41, has ridden a bumpy ride of institutionalism, hospitalisation, parental estrangement and drug addiction.

He has come out the other end, and in the last few years has staged a one-man show at the Adelaide Fringe Festival, acted in George Miller’s Mad Max Fury Road and now has his own radio interview program.

So what’s not inspirational porn about that?

Kenihan, who describes himself as a disability activist, says the last thing he wanted his disarmingly honest book Not All Superheroes Wear Capes (Hachette Australia) to be was “inspirational” in the cloyingly self-conscious way some stories about overcoming biological and medical difficulties can be.

“Back in 2005 I sent a draft to a publisher and it came back with 27 pages of notes that said this is too full of angst and doesn’t have enough celebrity stories,” Kenihan says.

He shelved the book but after the success of his stage show Quentin: I’m 40. Now What? he took the advice of comedian and writer Tim Ferguson (who worked on the stage show with him) to revisit his story with another publisher.

“I told this publisher that I didn’t want it to be full of celebrity stories and some sort of inspirational porn. I wanted people to understand the bullshit in my life as well as the good bits – that’s what makes up a life.”

And the result is a disarmingly honest and surprisingly affecting book that in many ways is as much about fame itself as about fame because of a disability.

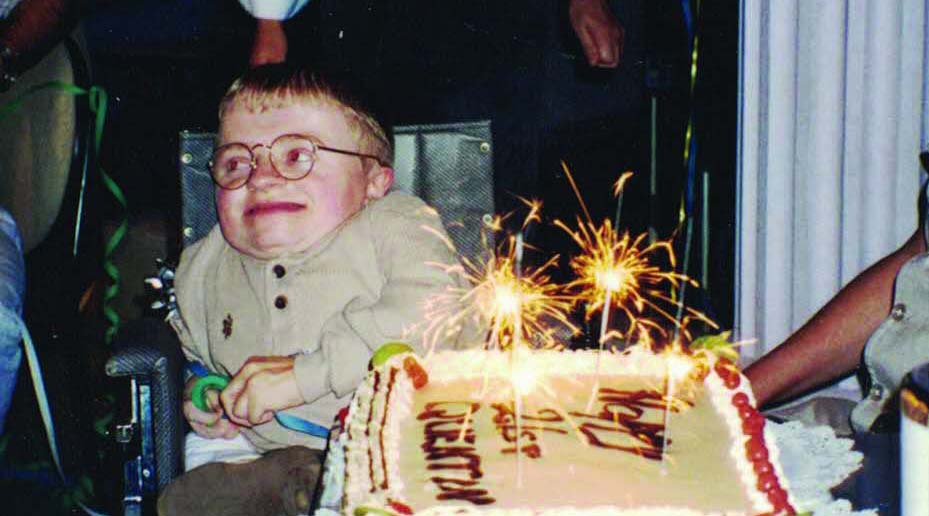

Quentin Kenihan at his 21st birthday party.

Its opening chapters describe his early childhood memories of parents, siblings, attending a regular school and the attendant difficulties for all of them in dealing with his condition. But from age seven after a “Make a Wish” exposure led to a Mike Willesee documentary that made him famous – or a “commodity”, as he describes it – there was increasing pressure on his parents’ relationship with each other and with him.

The book is heartbreaking and brutally honest when he describes his first night in full-time institutional care and when visits from his parents become fewer and fewer.

Usually if your child suffered a broken arm, you’d rush to the hospital to be with him, to comfort him, to take care of him and then to take him home to recover. That’s not what happened with me. My mother and father decided that I’d be okay by myself. After all, it wasn’t like I hadn’t broken an arm before. If anything went wrong, they figured the doctors and nurses would be there to look after me. I was stunned. It was the first time that I had been to hospital in years and my parents didn’t bother to show up. How could I think anything other than that they didn’t care about me anymore.

Where’s a pair of ruby slippers when you need them?

That was it. I hated them. I hated them with a passion after that. Everything I had ever thought about them had been a lie; all the good they’d done in my earlier years had been thrown out the window. They didn’t come the next day or the day after.

I was taken back to Regency Park Centre and didn’t see my parents for a full two weeks. When I did, my father rocked up one Friday night to pick me up and he was obviously drunk and reeked of alcohol. The house parents decided that he was too inebriated to drive and they wouldn’t let him take me with him. Dad got angry and said they couldn’t stop him, as he was my father. The house parents threatened to call the police and that was it. Dad went home without me.

I didn’t mind. I didn’t want anything to do with Mum and Dad. It seemed to me that all they cared about were their careers. Mum was a respected travel writer and was jetsetting all over the world. Dad was a lead writer and columnist for the Advertiser and he was busy too. Sia and Myles got to stay home with Dad or they stayed with relatives if Mum and Dad were ever away at the same time. I was stuck in Regency Park. I didn’t want to talk to my parents on the phone, I didn’t want any part of their lives. Not anymore.

He says he’s reconciled with his mother (his father is now dead) and she read the manuscript before its publication.

“My relationship with my mum is better than ever. I love my mum. She’s not the person she was then. She doesn’t drink anymore or sit in an office. She’s spending time trying to do stuff for her family now,” he says.

The book does contain some celebrity stories (including pages of photographs of Kenihan with an eclectic line-up – Prince Albert of Monaco, Jewel Kilcher, Jimmy Barnes, Julia Gillard, Angelina Jolie, his good friend and mentor Russell Crowe and, of course, Mike Willesee).

The stories of Willesee, in particular, are honest and not always flattering. They are revealing of the strange relationship between journalist and subject and their odd and intermittent relationship that has continued over decades.

The first interview was harmless but during the second one Mike asked where my friends went when they died, what I thought would happen if I died and how important it was for me to succeed whilst in America. What the …?

If you watch the footage you’ll think I answered the questions in a cute, charismatic, childish way but as an adult looking back at his childhood self I think that the questions Mike asked were highly inappropriate. To this day, I think, ‘How dare he!’ Why would you ask a seven-year-old boy, going through the biggest struggle of his life, aware of friends dying around him, about mortality, God, death and what heaven is like? Wouldn’t it have been better to let the child be a child and allow him to go through these struggles privately, with parental support and without having to focus on these dark thoughts? I am sure I thought about death and dying at the time but I didn’t want to confront these fears on camera. It still makes me angry and I guess I am angry with my parents, too, for allowing me to be in that situation, even though it was with good intentions.

Whilst all this filming was going on, I was back with Wally Motloch getting fitted into a new set of leg braces and a brand new walking frame. I would also go to see the physiotherapist, Barbara, once a day for an hour and a half and she would exercise my legs, core muscles and balance so that my small body was fit enough to take its first steps. To say my time, energy and patience were stretched was an understatement.

It wasn’t just the questions or the shadowing that were the problem with being part of the documentary. At one point, Aviva thought it would be a great idea for me to be filmed listening to the motivational tapes that my father recorded and sent over for me whilst I was in the bath. I was not comfortable with this at all. I didn’t want strangers like Aviva, Brian and Mike seeing me naked. Not to mention the thought of my penis appearing on camera for all of Australia to see. They assured me and my mum that my penis would not be filmed.

Aviva also thought it would be a great idea to get footage of my mum and me riding on a cable car in San Francisco. During part of the filming, Brian slipped over and his leg went under the cable car. Mum kept a hold of me with one hand and reached out and grabbed Brian with the other so he wasn’t crushed to death. He ended up with a large gash to his leg and it was all pretty traumatic.

The final interview between Mike and me will always be the most memorable because instead of treating me as an adult he finally came down to my level and made the interview fun for a kid. He started off by saying, ‘I’ve interviewed about eight prime ministers and you’re harder than all of them put together.’ He turned it into a game. If I gave a good answer I’d get a point, if I gave a bad answer I would lose a point. If I got five points we would go to the toy store and I could pick whatever I wanted.

Where do you go when you die?

Finally, he understood. Mike got the interview he wanted and I got a Han Solo Star Wars Blaster. Oh yeah!

“Before it was published I told him that I was going to give him a few hits in the book and he said, ‘Yeah, well I can handle that’.”

“Before it was published I told him that I was going to give him a few hits in the book and he said, ‘Yeah, well I can handle that’.”

The book also addresses the pressures of dealing with the bouts of public attention that could be literally crippling – fans would shake his hand not realising they were breaking his fingers in the process.

Kenihan says the book was liberating to write.

“I wanted people to understand what was going through my head in certain situations. I’m told I can be arrogant, brash and dismissive but I wanted them to understand why.”

Not All Superheroes Wear Capes, by Quentin Kenihan, is published by Hachette Australia. It will be officially launched by Premier Jay Weatherill at Dymocks Adelaide on October 5.

This article was first published on The Daily Review.