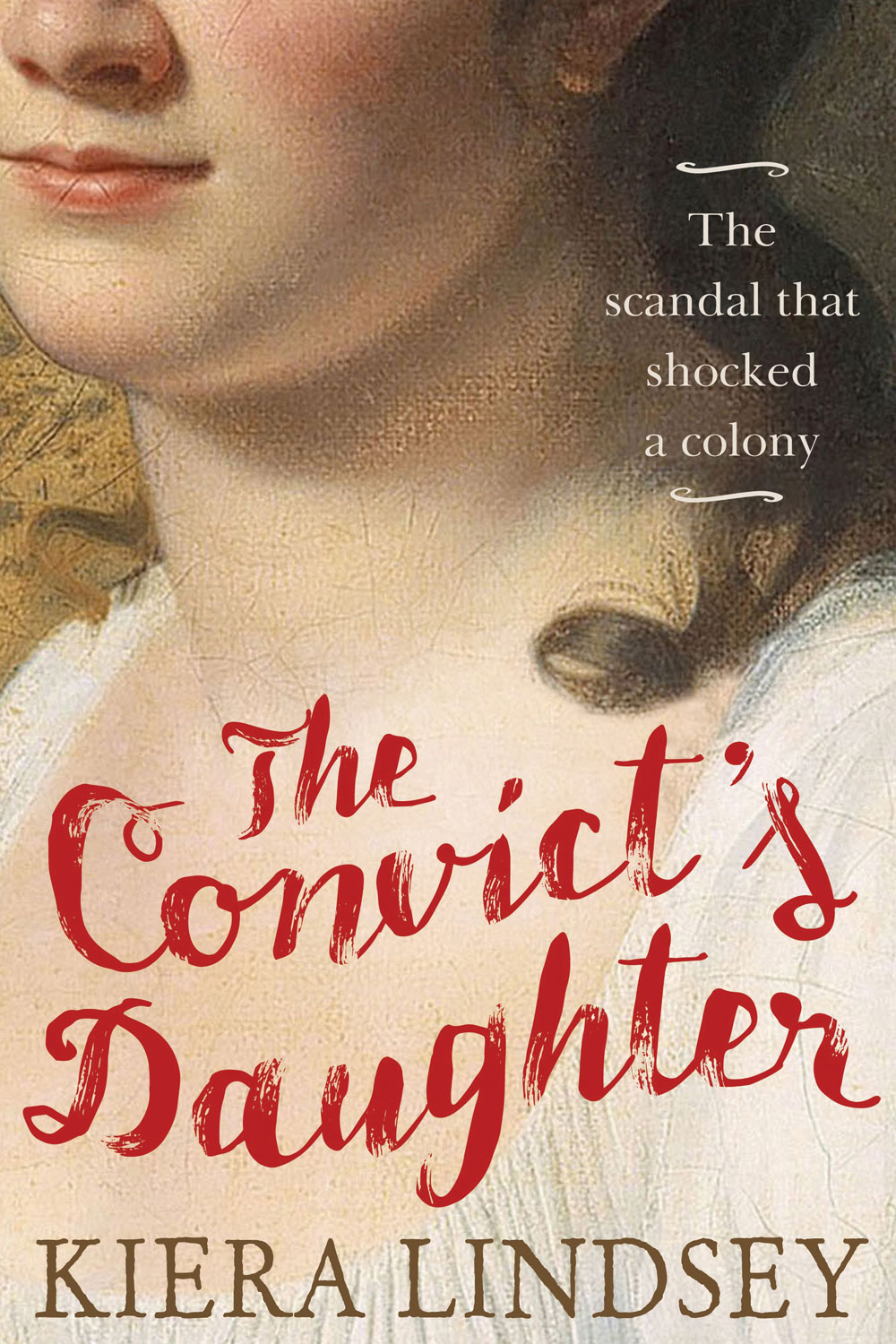

Book extract: The Convict’s Daughter

Adelaide writer Kiera Lindsey’s historic tale ‘The Convict’s Daughter’ was inspired by her discovery of a newspaper clipping about a feisty relative who ran away from her family’s Sydney hotel in 1848 to elope with a “gentleman settler”.

A slice of Sydney life in the 1800s: George Street, Sydney, by Alfred Tischbauer, 1883 / Wikipedia Commons

Lindsey, a lecturer in Australian history at UniSA, delved further into the archives to unravel the full story of Mary Ann Gill (her great-great-great aunt), whose romantic misadventures led to what has been described as Australia’s most scandalous abduction trial of the era.

The case was covered extensively by newspapers of the day, which lapped up salacious details, including the fact that the teenager stopped briefly in the parlour of a “house of ill repute” on her way to meet up with suitor James Butler Kinchela, and that her angry father chased them on horseback and shot at Kinchela at the racecourse.

This extract begins with Mary Ann slipping out of her bedroom to meet up with Kinchela, who had promised to marry her.

***

With both hands gripped around the drainpipe that travelled down the back of her father’s hotel, and well out of sight of the main thoroughfare, Mary Ann stopped and cast another glance back at her bedroom window. She was contemplating climbing back inside and staying there. Actually, she wanted to step inside and find herself back in her York Street bedroom at the Donnybrook, the one she had shared with William and Isabella when she was still a child. Just days ago, the smell of her younger siblings had annoyed her, but now the sound of William’s uneven breathing and Isabella’s soft inhale made her long for her childhood.

But instead Mary Ann fossicked about in the dark and when she found a small niche in the brickwork for her boot to grip onto she eased herself off the ledge and put her whole weight onto the drainpipe. She made a horrible job of edging herself down it and halfway through she caught her calf on a bit of nail that was jutting out. A few clumsy minutes later it was done. A tear of blood trickled towards her boot. She knelt and dabbed at it with the inside of her petticoat and, for a second, an image of the Hanley girl flashed to her mind, legs bound and floating in the pool of seawater.

It was about nine o’clock on a Saturday night and the street around the hotel was unsettled from the windy mess of the day before. It was growing darker. She would need to walk quickly if she was to get to Somerville in time. Her father had friends all along Pitt Street and up on George Street, but she and Kinchela had agreed that she would stop for a few minutes in the front parlour at Mrs Kelly’s, off Castlereagh Street, so a note could be passed on to James at the Adelphi. Then she would head behind the police station, of all places, to the coach yard where Somerville would be waiting.

Down this end of town, Pitt Street was so wide that her only hope of not being seen by the shop owners and hotel men who knew her father was to hide herself within a crowd. But for some reason—other than a few stray dogs—the street felt curiously empty. Mary Ann pushed on until she arrived at the Vic Theatre where a cluster of Cabbagers were mingling about the front gates, clearly intent upon mischief. She knew well enough to keep her head down. One boy called out, but before the group could get organised she was off, too fast for them to bother. After another wretched ten minutes or so she knocked on the appointed door and a buxom woman, older than her mother, appeared, her hair piled high above a face that was both tough and flabby. ‘Miss Gill,’ she nodded, offering the girl’s name as a statement rather than a question before ushering her inside.

Mrs Kelly’s place was not pleasant. Mary Ann could see that, even from the front room. She had no business in a place like this and if her father ever found out she had been there he would be right to belt her. Some sort of smoke hung low and heavy in the corridor. She shuddered as she sat down. The plush and lush of it. It was like nothing she had ever seen before. Low and dark with muffled laughter elsewhere— but inside the room—heavy quiet.

After what seemed an eon, a girl, younger than Mary Ann, with loose plaits and a stiff walk, came in and asked for the note. Mary Ann had not thought to write anything in advance so she requested some paper and ink. This elicited an expression of irritation from the girl, which Mary Ann assumed had its origins in Mrs Kelly. But eventually the paper was presented, the note written and sent on to the Adelphi. Then she waited, trying not to look at, to even be in, this place. Why had James sent her here? What was he thinking? Surely this was not fit for a gentleman’s wife, she thought as something began to stir inside Mary Ann’s stomach. Already this was not the sort of adventure she and her school friends would have recounted to one another from the stories they read in books.

It was a relief when she finally left Mrs Kelly’s, even if it did mean heading back out into the night. Another downpour had made the street wet and it was also much darker than when she had arrived at the house, but Mary Ann was glad to be free. Mrs Kelly’s girl had given her a drink. Something brown and sweet in an etched glass that was meant to keep her warm and steady her. After a few sips Mary Ann felt lighter in her step and somehow also dazzled. To keep herself steady she trailed her fingertips along the rough brickwork of a low wall that ran along part of George Street, before turning into Bathurst Street. She had to walk a strip that was known to be particularly rough. There was a broken cart parked on one corner where someone could be hiding so she made sure to take the other side of the street. Mary Ann knew her way around town from running errands, but everything looked different in the dark, especially when she was stepping beyond her father like this. She turned her head to look into one of the tumbledown shops and was startled by a brace of rabbit carcasses hanging from a window hook. Again she imagined the Hanley girl. The same age on the day of her wedding as Mary Ann and then a week later, dead.

Once more Mary Ann thought of turning back, but then the grey orb of the police station appeared through the night clouds, its weather- cock spinning in soft arcs with the wind. She shoved her doubts down and made her way into the coach yard. ‘Well then,’ said a corpulent man when he saw her standing beneath the entrance to the coach yard, ‘there you are.’ The man had been working on his letters while waiting for the girl. He wanted to get Kinchela’s job done so he could get off the wet night road and back to his slate.

‘You are Mr Somerville?’ Mary Ann heard herself asking, and when she received confirmation of this she moved further into the yard.

‘And you know where you are to take me?’ she followed. Somerville replied by hauling his great hulk from the chair and pointing out into the dark. ‘I’ll fix up the horses and we can be on our way.’ She refused his offer of a seat and instead stood counting the revolutions of the weathercock while she waited. Once, twice, three times it spun in the wet night air and then to her surprise it was not Somerville who spoke next, but James Butler.

Mary Ann turned in surprise. They were meant to arrive at Parramatta by different drivers. So why was he here? Wasn’t this bad luck? She could hardly breathe let alone speak, so she found herself nodding in response to whatever he said. ‘Yes,’ she agreed, ‘Webb’s Inn, the Sportsman’s Arms, out along the Parramatta road. Yes,’ she agreed again, thinking he must be planning to stop en route before they arrived at their final destination for the ceremony. ‘Ask to speak to a man named Healy and tell him about your father.’ She nodded, blood surging through her head. ‘I’ll be there within the hour,’ Kinchela reassured her as Somerville opened the door and beckoned her into a poorly lit and rather damp carriage.

Then Kinchela slapped the coach with the palm of his hand and stepped back. ‘We are just an hour or so behind,’ he said lightly. ‘All will be well.’ With that he closed the door and the vehicle lurched forward on its wheels as Mary Ann began her journey off and up and out along the open street towards the Sportsman’s Arms.

Extract from The Convict’s Daughter, by Kiera Lindsey, published by Allen & Unwin, $32.99. Republished with permission.