The monument man

How did a mostly unknown public garden in Adelaide’s eastern suburbs become a memorial to JFK? Simon Royal unravels the extraordinary story of the driven man behind the project and his painful past.

Then Prime Minister Julia Gillard holds the hand of John Hennessey during an official reception at Kirribilli House in Sydney in 2013. Photo: Tracey Nearmy / AAP

Tucked away in a corner of Adelaide’s eastern suburbs there’s a small, unassuming park. For commuters on the daily rush to work, it’s not much more than a quick green comma, punctuating the lines of homes and businesses flashing by. That’s a shame because the park, which is actually a memorial garden, honours one of the 20th century’s most significant figures: US President John F Kennedy.

Sadder still is the fact that despite the gravity of Kennedy’s name, the garden’s story has all but slipped away.

It’s a memorial that’s forgotten the memory of itself, along with the 26-year-old Irish house painter, and the Czechoslovakian refugee, who built it.

Like everyone else of his generation, John Michael Patrick Hennessey no doubt remembered exactly where he was, and what he was doing, when he heard the news John Fitzgerald Kennedy had been assassinated.

The Advertiser headlined Kennedy’s death as “The Shot Heard Around The World”, borrowing Ralph Waldo Emerson’s phrase heralding the birth of America’s democracy – the first revolutionary shots at Concord and Lexington.

In Australia, the gunfire from Texas echoed through a modest bluestone cottage in Main Street, Eastwood – John Hennessey’s home. Both Irish, both Catholic, and both bearing names as long as the alphabet, it’s no wonder Hennessey was drawn to Kennedy. Millions of people experienced JFK’s death as a matter of personal grief, but unlike most of those millions, John Hennessey wanted to give a tangible expression to how he felt.

Two years after the assassination, in November 1965, the Burnside and Norwood Review began a regular series of reports on the house painter’s progress.

“John Hennessey tells of his Rose Garden Plan,” the paper announced, before informing readers, “work on the building of the garden will officially start tomorrow. The United States Ambassador to Australia (Mr Edward Clark) will unveil a commemorative plaque and turn the first sod.”

Burnside Council donated the land, situated on the corner of Gurrs and Magill roads in Beulah Park. The Hollostone company of Pooraka donated the bricks used in the ornamental wall. By the time the project was completed, something like £1500 – more than $40,000 in today’s money – had been raised. The most charming detail, though, from that innocent era to our email-scam-weary time, is that one article even included John Hennessey’s home address. That was so the public could post donations directly to him.

“Who’d have thought in their wildest dreams that this whole thing would have snow-balled the way it has,” Hennessey told the Review. “I’m amazed at all the help and encouragement people are giving me. It’s quite obvious the people of South Australia wanted something like this.”

The story offered a small glimpse into John Hennessey’s personal life. He told the unnamed reporter that he’d been born in Belfast, moved to Western Australia first off, and had lived in Adelaide for the past four years.

“I could well imagine, if I did not have that break I most probably would be sweeping the streets of London today, ” Hennessey said.

That one line of copy tells a whole story of the ’60s – boatload after boatload of European immigrants coming to Australia, on the promise of a better life. There’s yet another echo, too, but this time a sweet one of JFK’s words from when he visited the Kennedy ancestral home in June 1963. Gesturing to a nearby fertiliser factory, the President told an adoring Irish crowd that if his great grandfather hadn’t set out across the Atlantic, he’d just as likely be working there. In a whispered aside to an aide, Kennedy added, “yeah, shovelling shit!”.

John Hennessey was quite particular about what he wanted in the garden. Roses, naturally, featured. Two dozen John F Kennedy commemorative rose bushes were ordered. But the house painter was more preoccupied with what style of hardware should grace the place.

“A bronze statue, while new, is nice, and is admired by all, but after a little while it seems to grow cold and less conspicuous,” Hennessey said, obviously wanting to avoid a public convenience for pigeons. A beaten copper plaque of Kennedy’s likeness was eventually chosen. Beneath it, another plaque carries the famous phrase from JFK’s inaugural address: “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.”

We don’t know how the sculptor, Voitre Marek, was chosen for the project. We don’t know when or how Marek and Hennessey first met, or how they felt about working together. But according to Elle Freak, associate curator of Australian painting and sculpture at the Art Gallery of SA, we do know that Czechoslovakian-born Marek was the perfect pick for the job.

“When I look at the plaque I think it’s in keeping with what Voitre is known for – being very thoughtful and sensitive,” Freak says, raising an eyebrow at the layer of ugly brown paint now covering the copper Kennedy. “I can see why Voitre would have been attracted to this commission… you can see from the inscription he’s brought his Catholic faith into the work.”

Elle Freak at the memorial in Beulah Park. Photo: Simon Royal

Freak says Voitre, and his younger brother, a painter named Dušan, came to Australia in 1948, fleeing the communist takeover of their homeland.

Before that catastrophe, the Mareks had been immersed in the whirl of Prague’s intellectual life, particularly the surrealist art movement. Voitre Marek loved surrealism because he felt it “turned the artist inside out, so that which was hidden, becomes visible”.

Freak has uncovered examples of Voitre’s sculptures in every state and territory. “He was hugely prolific… he created them for schools and churches, doing everything from crucifixes to candlesticks,” she says. “ Both Voitre and Dušan were part of this post-war influx of migrants and refugees who fuelled a wave of innovation in Australian art.”

Last year, Freak realised her long-held ambition to stage a major retrospective of the Mareks’ work, helping rescue the brothers from growing obscurity. But the art curator is also well aware that recognition is fickle with its favours.

“I’ve walked past this park multiple times without really realising that Voitre’s work was here,” she says. “I didn’t know the significance of the garden, but that’s so often the case with public sculpture… we don’t always open our eyes to what’s in front of us.”

Detail of the memorial plaque. Photo: Simon Royal

Eric Kontos is the editor of The South West Voice, an online paper he describes proudly as a “good, old-fashioned local rag”. Kontos was just starting his career as a journalist when he met a short man with a long name, who was just starting his career in local government. It was the early 1980s, 15 or so years after the completion of the Kennedy rose garden. John Michael Patrick Hennessey had moved on from Main Street, Parkside, to Sydney’s western suburbs.

“He [Hennessey] had just got on the Campbelltown City council here in Sydney, when I came across him,” Kontos recalls.

“He was obviously a bit of a character who stood out… he had different opinions. He even looked different – he was a little man. But he was very interesting, and you just knew he had a lot of stories to tell… I’ve known him ever since then.”

Over the next three decades, John Hennessey did his best to ensure he was part of a steady flow of community stories – the lifeblood of local papers. More often than not, Kontos found himself telling those stories. The journalist remembers Hennessey turning up to council chambers wearing a set of koala ears, as the fate of a local koala colony was being hotly debated.

“The mayor asked him to remove them and John said, ‘no’. He made it clear that he was on the side of the koalas.”

Kontos says Hennessey and the mayor, a man by the name of Les Patterson, “fought like cat and dog”, but later became the best of friends.

Another thing that stood out to Kontos was Hennessey’s interest in creating public memorials. Australia’s worst public transport accident, the Granville train disaster, happened in the Campbelltown Council district.

Eighty-four people were crushed to death on the morning of January 18, 1977, after their commuter train derailed, bringing a bridge crashing down on top of it. Hennessey was instrumental in building a garden in memory of the victims of that terrible event. When Nelson Mandela died in 2013, Hennessey helped organise a remembrance service for the great man.

However, not all of his ideas for public memorials met with support. Kontos says elaborate dreams harboured for one monument were shattered.

“He [Hennessey] wanted to build a glass statue of a local legend here, Fred Fisher, after whom we have a festival every year. Fisher was murdered over a property dispute.”

If a glass statute seems a little eccentric, it should be noted the legend isn’t so much about Fisher, as it is his ghost. Apparently, the apparition appeared to travellers in the 1820s, pointing a finger at both its hastily buried remains and the killer. Presumably glass, as opposed to bronze, would have given a suitably spectral effect to the plans floating around in Hennessey’s head. Kontos notes, with a touch of regret, that council voted down the proposal because of the cost.

“I think John was a bit of a visionary,” Kontos says. “You know a statue like that puts a little suburb on the outskirts of Sydney on the map… people would come to see it.”

John Hennessey at the memorial he founded near Granville train station in Sydney in 2002 – the 25th anniversary of the Granville train disaster. Photo: Laura Friezer / AAP

Ordinary people going about their day on a train. A president martyred in the midday sun. An imprisoned freedom fighter who forgave his jailers. John Hennessey threw himself equally into the preservation of their respective memories. But why do it?

Eric Kontos knew the man as well as any person: he knew Hennessey loved being in the media – a “media junkie”. Like the rest of Campbelltown, Kontos could plainly see Hennessey was devoted to his community, eventually becoming deputy lord mayor, and scoring an Order of Australia for his efforts.

Kontos even knew some details of John Hennessey’s terrible childhood. But there are things the journalist wasn’t aware of: Hennessey’s championing the Adelaide Kennedy garden, for example, was news to him. And despite all the stories written, Kontos says he’s still not really sure what drove Hennessey to remember the triumphs and tragedies of others.

“I don’t want to pretend I’m a psychologist,” he says. “I don’t know, maybe he needed to show he was worthy, but I’ll leave it at that, because we’re journos, mate.”

No one would build statues honouring John Hennessey’s memories. Indeed, some people fought to ensure they were kept out of the public gaze completely. But as the years went on, and the former house painter turned local councillor discovered more of his past, he became determined there’d be no forgetting what happened to him.

In 2014, Hennessey recounted details of his childhood at a place called Boys Town, which was run by the Christian Brothers in Bindoon, Western Australia. Hennessey’s audience was the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses into Child Sexual Abuse.

When he was 11 years old, John Hennessey was taken from his English orphanage and put on a boat to Australia. At the time, he believed his mother was dead, and that he’d been institutionalised because she’d scored an unholy trinity: Irish, Catholic, and unwed. As they headed down to the wharves, all the children from the orphanage were told that in Australia they’d be able to pick fresh oranges from trees, and ride kangaroos to school.

“We landed at Fremantle. I now know this was in November 1947,” Hennessey told the Commission.“ It was a stinking hot day. We all had white Pommy skins and were wearing our suits. There was a band to greet us. I remember feeling a sense of great excitement.”

That was the last day in a long while when John Hennessey would feel excited about his new Australian life.

It’s difficult to single out a most shocking event from the litany of betrayal and abuse that children like him suffered at Boys Town. Perhaps it was that first year they spent sleeping on a verandah open to the elements, or the beatings, rapes, sexual, and physical assaults? Or maybe it’s the everyday little cruelties, such as constant hunger from meals of Dickensian inadequacy? At breakfast, the Christian Brothers had bacon, eggs and coffee, while the children ate thin porridge and stale bread.

Not even John Hennessey’s name was left unmolested – he told the commission it was changed by the brothers. His mother had christened him Michael Patrick Hennessey. In the end, of course, there was no single most shocking event – just the fact that a little boy, after spending five years in that place, saw his treatment as his birthright.

“I believe the Brothers felt we were children of the Devil,” Hennessey said. “We were not children of God. Because we were born out of wedlock. We were not normal children.”

With help from the Migrant Children’s Trust, he pieced together a more complete picture of his early life – one that included the mother he’d been told was dead. He got to know her about six years before she died – they spent some precious time together at last.

There were other lies, too. Though conceived in Ireland, Hennessey wasn’t born in Belfast: he’d been born in Bristol. Completing that circle of deceit, Hennessey’s mother, Mary May, was told her infant boy had died at birth. Also hidden in the shadows was a great big extended Irish family. In 2014, about two years before his death, John Hennessey got to meet that family.

A happy photo was snapped in Dublin of a family having dinner together (above). Everyone has their arms linked and is smiling for the camera.

Hennessey’s third cousin, writer and broadcaster, Deirdre Mulrooney, told InReview that although John Hennessey was described as short, his presence made him seem large.

“We are very touched by our connection to him, what he’d achieved, and what he went through,” Mulrooney says. “But really, that evening he was more interested in listening to us than doing the talking himself. The one phrase I remember John Hennessey repeating about us over and over again that evening was, ‘flesh and blood’. It meant so much to him to finally connect with people who were his own flesh and blood.

“He was obviously proud of his Irish roots – no matter how dark and tangled they were… organising the rose garden in memory of JFK. It’s very moving.”

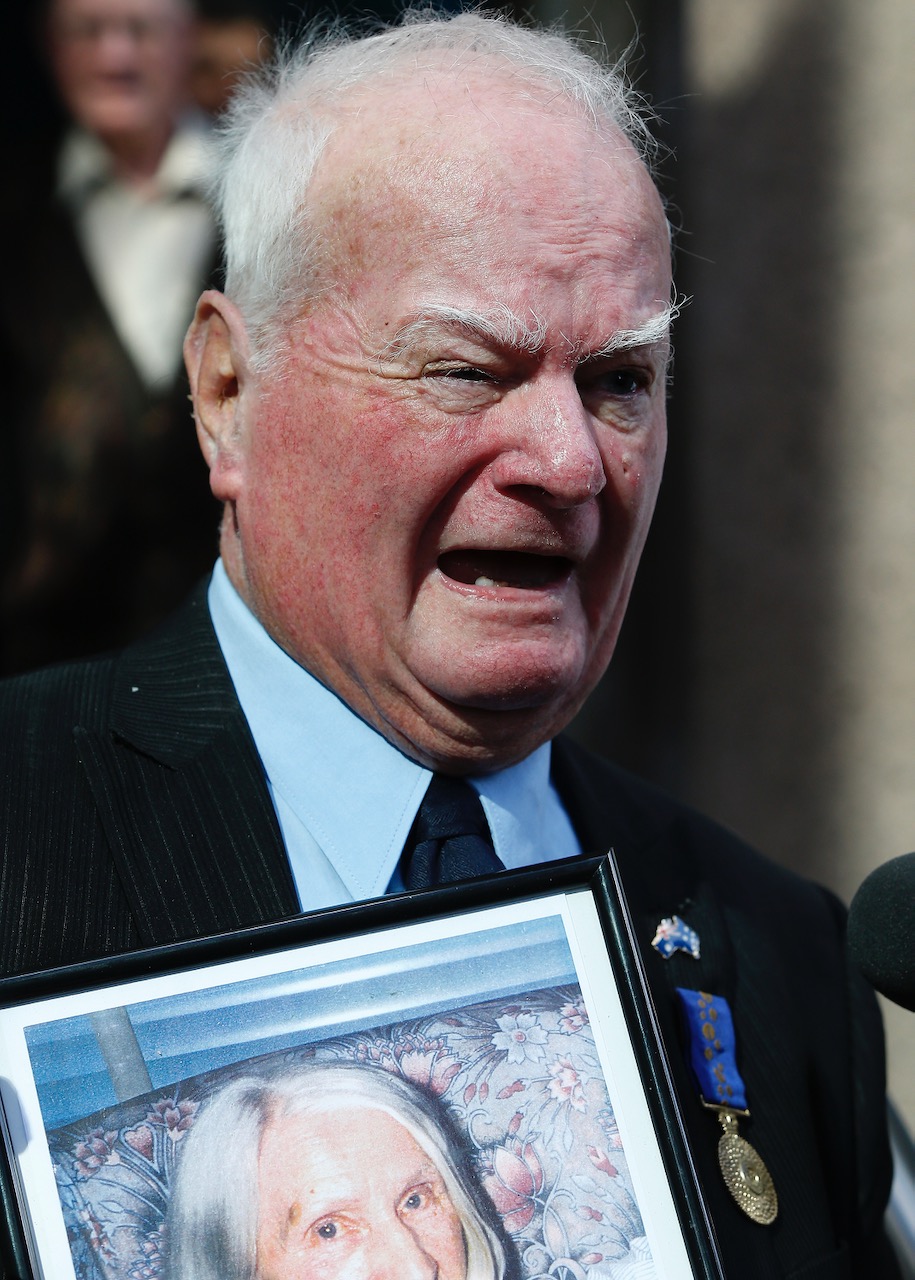

An emotional John Hennessey speaks to the media after giving evidence at the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse in Perth in 2014. He’s holding a portrait of his mother. Photo: Theron Kirkman / AAP

Like Eric Kontos, the Kennedy garden came as news to Deirdre Mulrooney. She’d not seen the Burnside and Norwood Review before. As she read the 1965 story for the first time, Mulrooney was reminded of how heavily the past weighed upon John Hennessey.

“I’m struck by his presentation of himself as being born in Belfast, and having lost all of his family in World War II,” she says. “That is so poignant, considering the terrible truth we now know, that he felt he had to hide.”

John Hennessey never married. He told the Royal Commission: “I have basically lived my life alone. I have never had a committed relationship… I lock my doors and keep people out.”

That is both the awful legacy, and life-long dilemma, that Bindoon gifted Hennessey: he was unwilling, or unable, to risk closeness, but at the same time feared what “locked doors” inevitably bring with them – a life destined to be forgotten. When Kontos wrote his last Hennessey story in June 2016, he gave it the title, “Vale John Hennessey, Campbelltown Icon”.

“They played the bagpipes and everything, and I thought to myself, ‘he was a good fella, he was a good human being,’” Kontos recalls. “That was pretty much my thought when I left that funeral… a good human being.”

It turns out the old journo, loath to play amateur analyst about his friend’s motivations for memorialising others, is closer to the truth than he reckoned – John Hennessey did indeed want to feel worthy, and he wanted to be remembered.

With the help of a surrealist artist, Hennessey started to tell the world about himself through a small garden in Adelaide.

John Hennessey finished his story with these words to the Royal Commission: “I have picked myself up out of the gutter and I have tried to serve society. I did not want to be a nobody.”