Artist makes the microscopic monumental

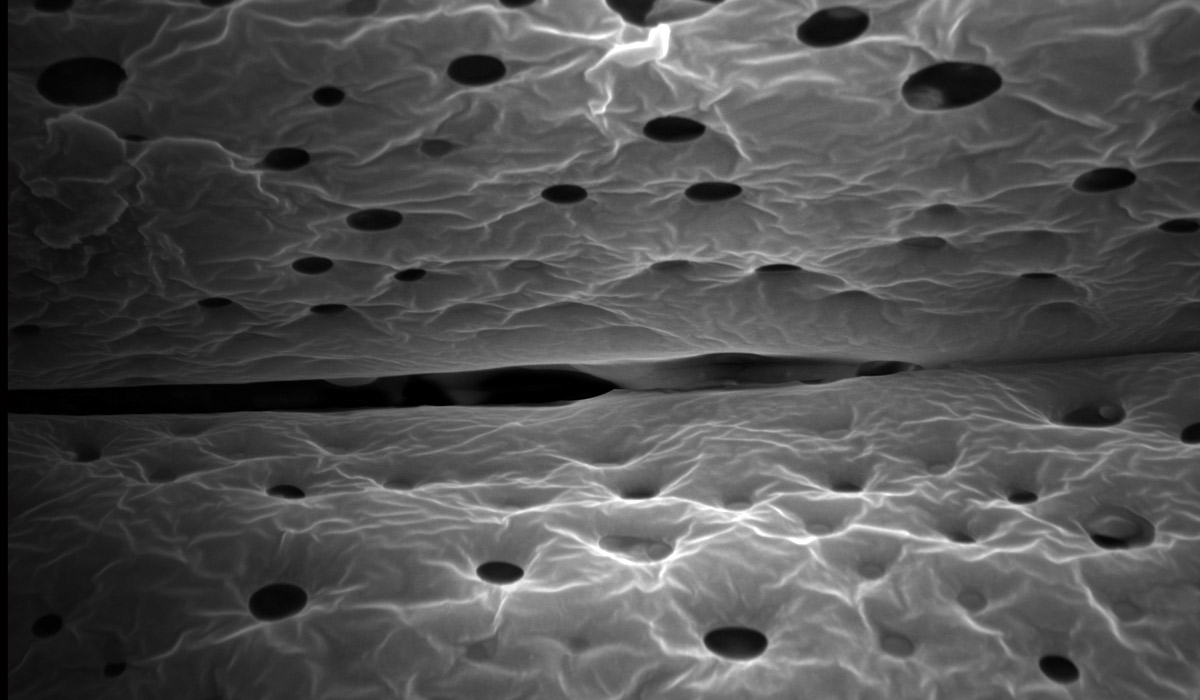

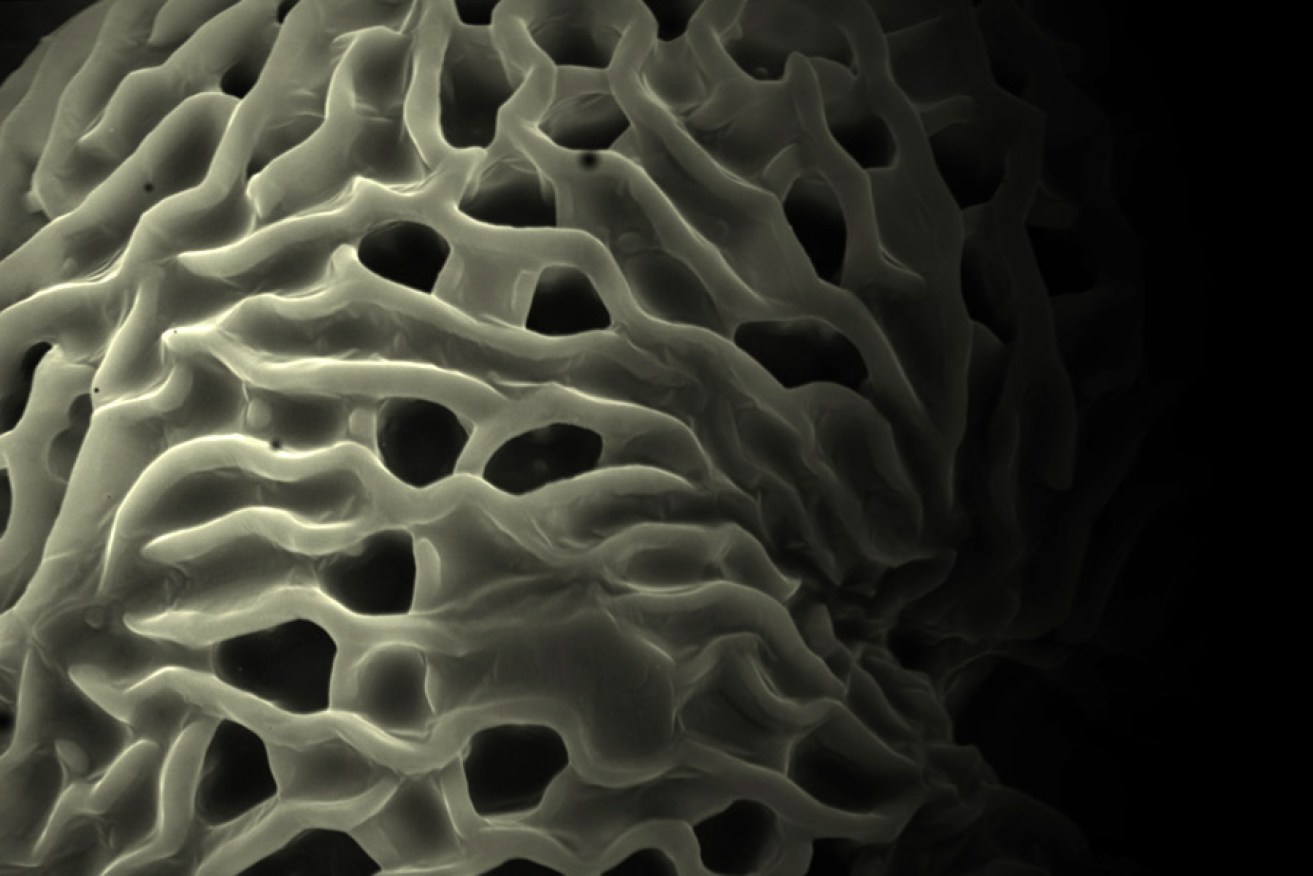

One of the microscopic images Jessica Lloyd-Jones will be projecting onto the Adelaide Festival Centre.

“I sometimes need to undertake a bit of research and reading before it sparks a creative idea. Science can be a very artistic medium, especially in different types of imaging processes,” Lloyd-Jones says.

Blinc, a city-wide exhibition for the Adelaide Festival, will see the city engulfed in lights and projections. Eerie faces will appear and disappear in clouds of smoke, a three-dimensional elephant will stomp through crowds in a bar and clouds of bees will swarm above the city.

UK-based artist Jessica Lloyd-Jones is bringing another world to life as part of Blinc. She’s marrying science and art as part of her public display Small World, draping the two in a heavy cloak of dark science-fiction – she’ll be making the microscopic into something monumental.

“It will reveal the invisible microscopic world of Adelaide, transporting viewers into another realm – somewhere they’ve never been before,” Lloyd-Jones says.

She has been working with the University of Adelaide’s Microscopy Centre to image an array of tiny objects found around the city and its surrounds. Audiences will see pollen, insects, minerals and fossils – usually minuscule objects, this time projected massively and forebodingly on the side of the Adelaide Festival Centre.

“The geometric shape of the Festival building is almost like a microscopic form in itself – faceted like the crystal structure of some kind of a rock or mineral,” Lloyd-Jones says.

The final result, the images she animates and brings to life using video software, is a visual wonder that takes viewers on a journey through its microscopic landscapes.

“The microscopy team can use the SEM (scanning electron microscope) machine to image specimens at different levels of magnifications – from observing the whole form to getting really close up, right into the patterning and texture. This has enabled us to create zoom effects within the artwork, and that has enabled us to play with the idea of worlds within worlds,” she says.

These textures will run like a kaleidoscope over the Festival building, some magnified over a million times as they split and fragment over its surface.

“This is when it will have a truly powerful visual impact. Pattern and repetition is consistently present in nature and we would like to celebrate that.”

The specimens that the Microscopy Centre has imaged for Lloyd-Jones are often invisible to the naked human eye. Alien patterns and textures cover these hidden objects, inspiring Lloyd-Jones to take a sci-fi creative approach to the project.

“I’m interested in the boundary between what is science-fiction and what is science fact. It’s a very fine and blurred boundary that also changes with time – what was science-fiction in the past is the reality of today. Take touch screens, for example.”

Small World will be accompanied by sound. Lloyd-Jones is working with Ant Dickinson, a collaborator on a similar projection project she put together in the UK.

“We’re opting for a very different sound approach this year – more dark and synthesised to obtain an eerie sci-fi mood with deep rumbles and drones, as if an earthquake is about to strike. He wanted to communicate the idea of something micro being monumental and colossal,” she explains.

Lloyd-Jones has been working with the open access facility at the University of Adelaide that has a raft of technology for imaging very small things. They work with researchers in nanotechnology, chemical engineering, medicine, plant science, geology, as well as companies, government, and artists.

“I like to find creative ways to interpret science and provide a different perspective of the world in which we live”

Students from other universities are free to train on and use the microscopes for their projects, too. It’s an open pool of resources for those with the need for high-resolution imaging.

“It crosses all faculties and schools. We work with researchers from diverse areas of science and engineering,” says Angus Netting, director of Adelaide Microscopy, the Centre for Advanced Microscopy and Microanalysis.

Netting is an industrial chemist by trade, and the centre’s staff are not strictly academic – they come from various fields of practical science.

“Some of the microscopes we have are as cheap as $100,000. The new microscope that’s being commissioned in the centre in March is worth $3.5 million,” Netting says of their atomic resolution transmission microscope.

The centre is being partly torn apart and put back together again to make room for the new microscope, but it’s a still a spectacle. The staff are busy in various labs – some devices sit on desks, others take up whole rooms. Some rooms are darkened, and the lights and lasers from microscopes play against the fluorescent images they’re capturing.

“Her (Lloyd-Jones’) big issue is that the images needed to be very high resolution,” Netting says. “We’ve gone back and recorded new images so she’s able to project them and expand them out. I think she’s someone who’s passionate about the link between arts and science.”

Netting is, too – and he thinks that art is a great unifier when it comes to communicating science. He recalls talking with a plumber working on the centre refit who was fascinated by the image of a gecko’s paw, covered in hundreds of fibres.

“He was also looking at lenses. One of the colour images in the tea room is a drosophila, a fruit fly. One of its eyes looks like the side of the SAHMRI building – hundreds of lenses that look fantastic when they’re coloured.”

Lloyd-Jones finds that science is hugely inspirational for her artistic endeavours.

“I need to undertake a bit of research and lots of reading before it sparks a creative idea. Science can be a very artistic medium, especially in different types of imaging processes,” Lloyd-Jones says.

Netting notes that the first Europeans to visit Australia created art in their scientific endeavours – he points to the work of Joseph Banks, a botanist who drew pictures of the native plants and birds he encountered to take back to England.

“We look at those images today and we say they’re beautiful, they’re artistic. Before they had digital cameras, biologists would look down an optical microscope and draw what they saw. They didn’t have photographic plates, so you relied on their perception of what they saw,” Netting says.

Lloyd-Jones adds: “Ultimately, science is there to find answers and fulfils an important practical role in people’s lives – however, I like to find creative ways to interpret science and provide a different perspective of the world in which we live.”

A taste of what’s in store at Adelaide Festival’s Blinc.

When the lights turn on for Small World next month, Netting and his team will be among the first ones there.

“We all wandered down North Terrace and saw the projections that went up on the buildings a couple of years ago,” he says, referencing Northern Lights, a predecessor to this year’s Blinc.

“I had visitors from Austria and took them down. They were really impressed. It’s quite a European thing.”

Lloyd-Jones hopes that, like her other artistic works, Small World will open people’s eyes.

“I hope it will make people think a bit differently about the world around them and consider that our world is not just what we see and hear, but that it has other dimensions, both in the microscopic and outer space,” she says.

“It provides a whole new perspective and way of discovering the area. It’s beauty and wonder on a different scale.”

This article was first published on The Lead.

The Adelaide Festival, including Blinc, opens on February 27 and runs until March 15.