Grenache, Gippsland and the Patritti connection

Whitey thanks the Italians that his first ever glug was the G-drop.

Saved by the Italian community: Bernard Smart and his son Wayne in their 1921 Grenache at the top of the Onkaparinga Gorge. Photo: Philip White

It came as a certain relief to confirm today that Grenache was the first wine I tasted. I’d long been suspicious that those dregs of vino famiglia I’d pinched as a toddler were Grenache but it was too far back to track.

Which led to living content that my first confirmed glug of the G-drop was from a Hardy’s flagon in the bushes of the carpark out the back of the Crafers pub when I was a high school kid. But this very morning I discovered it had indeed occurred at those previous tastings 10 years earlier, at our Italian neighbours’ place in Victoria.

We lived in the Strzelecki Ranges in Gippsland. The Bagnara family, sharefarmers from the mountains north of Venice, lived through the pines, just across the sandy Old Leongatha Road.

Giacomo “Jack” Moscato, patron of many immigrant Veneti families, and Attilio “Artie” Bagnara had built a boccé court beneath Artie’s backyard cypress trees. When I was a little kid I’d lie in my bed with the window open, listening to the clack of balls and ka-chink of beer glasses well into nights decorated with all the excited exotica of a romantic language I never knew, applied by laughing, tiddly people to a game of bowls anyone could play.

That joy was much more alluring than the Exclusive Brethren who’d gather for worship in our big room, with their

” … hymns exhaled through trembling wattles;

pious old throats filled with the Holy spit

and sanctimonious halitosis.”

It was a great relief to discover Federico Fellini 20 years later. His movies confirmed to me how exotic and romantic and foreign all that Italian stuff really was to a little blue-eyed Brethren kid in the hills at the bottom of Australia. It wasn’t a dream after all. I had good cause for my infant jealousy and wonderment. I lived like the boy in Amarcord.

While the men were in the cowsheds and the women busy in the kitchens making breakfasts, I’d wander across the track in the mornings after big boccé nights, just to try the odd cigarette butt, leftover beer, or homemade red wine. I was a connoisseur by the age of seven.

Us Whites lived in a very white house where we ate even whiter food: porridge and vienna slice; lettuce and radishes; boiled cauliflower and cabbage; corned beef. White tea. No alcohol, prawns or pork.

Instead of holding an uncle still twitchy from the war, the Bagnaras’ verandah sleepout was hung with home-cured meats; their shelves stacked with pickled jardinière and olives. They always had cheese with a lot more character than the stuff at our joint, but then Artie had grown up making cheese in Italy.

Fiorina taught me to hold the little wooden grinder between my legs to grind the morning coffee: I had never inhaled anything so good. Until Artie would add a few drops of his plum grappa to the tiny ones she’d serve him. That smelled even better.

From the way I watched others regard it, Jack Moscato usually seemed to have the best vino. He drove a Simca Vedette, with the steering wheel rubbing a stain into the shirt that stretched over his fat belly. He’d nevertheless manage to tuck a half-gallon flagon there in the vicinity of the thighs in case of being interrupted by sudden thirst.

The Vedette had the 2351cc flathead Aquillon V8 with the double-barrel Zenith, and when he opened the bonnet more men gathered to perve and share his flagon than I recall showing up to watch the Sputnik sail silently across one speckled night.

The Panozzos drove a Citroen DS, which was much more Sputnik as far as aliens went. I’ll never forget first seeing that spaceship float up the village street. Mum was as shocked as me. I instantly loved it more than my previous beau, the faux Americano Vedette, which used all its wings and chrome to look bigger than it was.

At the same time, in the northern suburbs of Adelaide, Giovanni “John” Amadio still grew bush vine Grenache and Mataro on Montacute Road. He owned the brand name Dry Table Wine and through and after World War II sold most of his product in barrel to the Australian government, which served it to the Italian prisoners of war we’d locked up in the gulags along the Murray.

They were our enemies at war, yet Australia gave them wine with their meals: a far cry from the way we ignore international law to punish honest refugees fleeing from the undeclared wars we’ve waged ever since.

Just as John Amadio went to the Riverland for the Shiraz he’d add to his suburban Grenache and Mataro, I’d always romantically imagined the Strzelecki Veneti crossed the Australian Alps to find Grenache on their northern side, in Rutherglen, and the King and Ovens Valleys, where other Italians grew grapes and tobacco.

Rae and Drew Noon in their old Grenache vineyard on the Willunga Escarpment piedmont. Photo: Philip White

Then Drew Noon told how the old blokes at Langhorne Creek recall sending Grenache bunches in boxes to the Melbourne market where Italians would buy them for backyard winemaking, so I thought maybe some of that found may have found its way east to the mountains …

My dear Kangarilla neighbour Bernard Smart, who I regard as the senior Godfather/Protector of McLaren Vale Grenache, recalls sending his grapes in banana boxes to the markets of Sydney for the same purpose.

Premier Don Dunstan loved living among the Italians in Norwood. He’d joke about his suburb being easy to find in the summer: all one had to do was look for the cloud of gourmand vinegar flies. Best palates on Earth, he reckoned.

Only when I moved south did I learn where many of those grapes had grown.

Bernard’s two upland Grenache vineyards survived due to his appreciation of the Italian community’s love of Grenache family wine. Once port was out of fashion, those of English or German backgrounds were disdainful of the variety they had planted everywhere to make that embarrassing plonk. It had been their invention. Now they didn’t want to know.

Apart from bits and pieces of dry Grenache finding its way anonymously into blends with Mataro and Shiraz in things like that Hardy’s flagon, or back before cubism struck, even d’Arry’s Red Stripe, Grenache was rarely seen to be a particularly good grape for premium table wine.

So prices fell and vast spreads of old pre-phylloxera bush vines were bulldozed and burnt, all the way along the Ranges from the Cape to Clare. It was horrible.

Fortunately, Bernard Smart hung on. Having grown up working his forebears’ old bush vine Grenache on the ridge between Baker’s Gully and the Onkaparinga Gorge, Bernard was not about to rip out the results of two or three generations of very hard toil. His kin began planting those vines in 1921. He had also to protect the big High Sands bush vine patch he planted on the next sandy ridge a few kays away in 1946.

Remembering the Italian demand for bulk Grenache grapes in Sydney, he’d simply sell his fruit to Adelaide Italians who’d come and pick it themselves into boxes, car boots and trailers. Back to the ‘burbs into the scrubbed laundry trough; through the home-made basket press and into that barrel on the back verandah she’d-a-go.

It wasn’t much money, but it kept those vines alive for another 25 years: just until the Grenache revival saw prices back up where they belonged. While I’ll tell Bernard’s story a bit further into this Grenache series, it was him relating his Italian tale yesterday that led me to recollect that vino famiglia beneath the sighing cypress a lifetime ago.

So after 55 or so vintages I tracked down Ittilio and Fiorina’s surviving son, Aldo, and phoned him in Gippsland.

Man, can we talk!

After scanning half-a-century’s gossip, I enquired where his community would have found the grapes for that home-made ’50s vino famiglia?

“It wasn’t home-made,” he said. “Every now and then we’d write to Giuseppe Patritti in Adelaide and he’d send a barrel by train from Adelaide through Melbourne and on to our local railway station at Yarragon. The station master would write to us and brother Flavio and I would pick it up with the tractor and trailer and haul it back up the hill.

“We’d have a big community get-together – like we did when somebody would buy a pig for smallgoods – and bottle it in rinsed beer bottles. Somebody even found little corks for them. There were no wine bottles.

“Nobody else in the district knew anything about wine or wine culture. We had the devil of a job convincing our non-Italian neighbours we never drank the whole 40 gallons in the one sitting!”

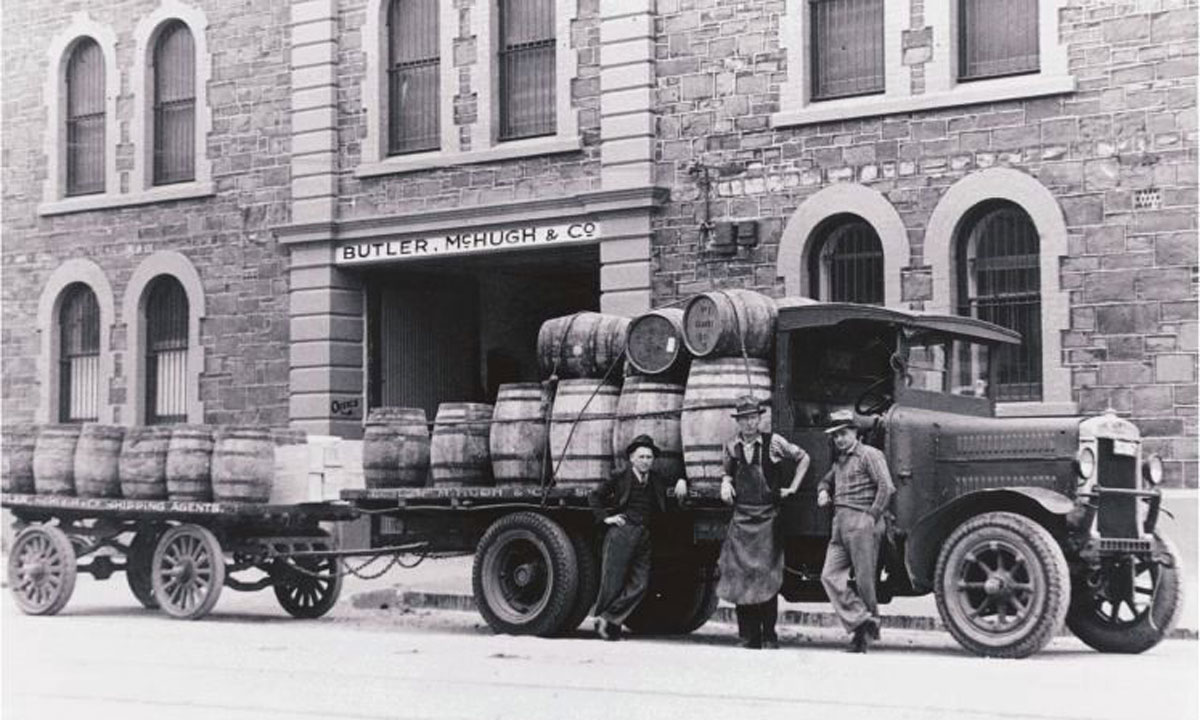

Patritti men making wine deliveries … date unknown.

So. My first red ever had been a Patritti Grenache, grown on that beautiful alluvium of Adelaide’s southern suburbs where only villa rash and Tupperware Tuscany now spreads. Apart, of course, from the tiny vineyard surviving on Oaklands Road, where the trouble this year was birds, not bugs.

And of course the Patritti winery’s still there in the houses, making fabulous old-vine Grenache. Go taste.

drinkster.blogspot.com