“The space between”: life, death and football

A long-forgotten photograph gives a rare insight into what drives Port Adelaide’s community ambassadors, as they deliver lessons on life, sport and indigenous culture to children living on the state’s west coast. Tom Richardson followed them on one such journey.

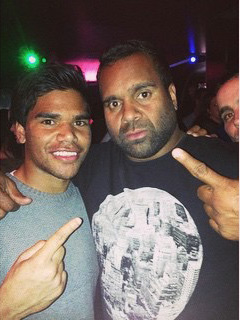

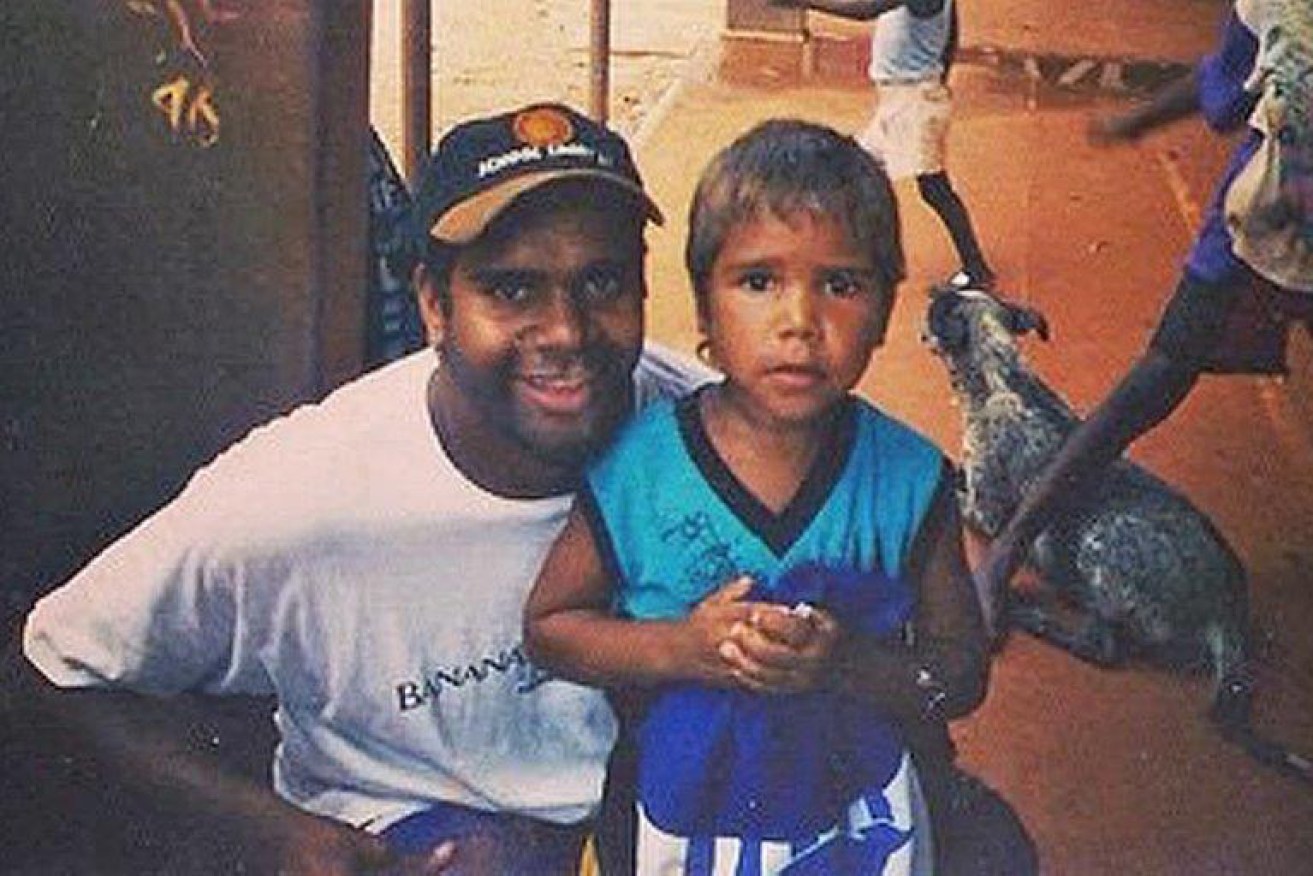

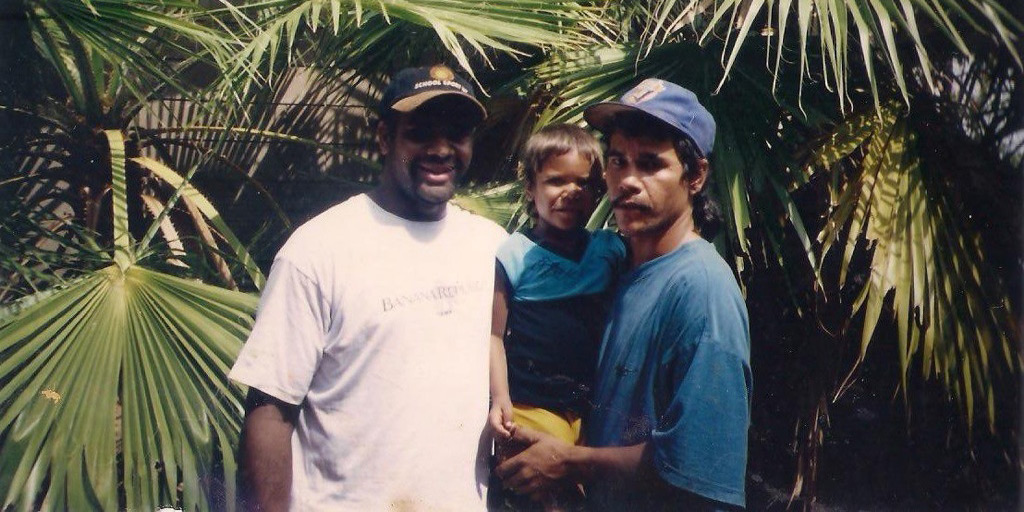

Then-Kangaroos star Byron Pickett with a young boy in the Northern Territory in the late 1990s. The boy, Jake Neade, now plays for Port Adelaide.

“For those of you who don’t know me, my name’s Byron Pickett … I played football for the Kangaroos, Port Power and the Melbourne Demons.”

The onetime hardman of the AFL, known as ‘Choppy’ to those who know him well, shuffles shyly before a gaggle of cross-legged primary school students.

“I’m originally from WA. The Kangaroos drafted me in ‘96 and I played there for six years. I played in two Grand Finals, winning one … and losing one against the Crows.”

A white boy in the audience can’t resist a smile and a silent fist-pump. Even at Ceduna Area School, on the state’s west coast, South Australian football loyalties are notoriously divided. Pickett should know. His own kids went here for a time.

“I was at Port for three years … I was part of a Premiership in ‘04 and was lucky enough to get a Norm Smith on that day. There were a couple of guys who could have got it but … they didn’t.”

Pickett shrugs. He has told this story before. This is the second time today.

If most of these kids were even born in his premiership heyday, they probably hadn’t broken a crawl. Nonetheless, they enthusiastically swamp him seeking an autograph, pressing him hard up against a mural, drawn and coloured in juvenile hand, that reads: “Don’t put your rubbish on the ground because you will wreck our beautiful town.”

***

“You don’t know this guy here? You should know this guy here!”

If Pickett’s onfield fame has preceded him, it is more apparent to Romolo Puccio than to the Year 7 class he teaches at Crossways Lutheran School.

While Ceduna Area School’s 600-odd students are predominantly white, four out of five of the 150 kids at Crossways are indigenous. The middle school co-ordinator’s lesson plan has just been thrown into mild disarray, as the four ambassadors from Port Adelaide’s WillPower program arrive a day earlier than arranged, and with me in tow, travelling on their dime and in their time.

The Port Adelaide Football Club has a mission statement to “win premierships and make our community proud”. The team pursues the first bit on the field; this program is part of the second.

The plan was five schools in three days, but the trip has been truncated by a death in the isolated Maralinga lands of Oak Valley, about 500 kilometres northwest of Ceduna.

Death, and its associated rites and rituals, is a big event in tight-knit indigenous communities, and in many an all-too frequent one.

Mourning – ‘sorry business’ – can take weeks, or more.

So the football folk have abandoned their sojourn to take a message of healthy eating to the Oak Valley school. There will be next to no students there this week.

Word of the altered schedule did not reach Puccio, but he takes the disruption with enthusiastic grace. His students may not remember Pickett’s bruising brilliance on the field, but they know he has come here from Port Power, and that is enough. That is more than enough.

“They do know him; probably not to a big degree, but they know him, because he comes out here with us all the time,” says Paul Vandenbergh, Aboriginal Programs Manager with Power Community Ltd, the club’s philanthropic wing.

“They know he used to play for the club (but) I guess their parents probably talk about him, more than anything.”

Round here though, just turning up in an official Power T-shirt is enough to see you mobbed by excited children, hoisting forward teal-hued footballs to be autographed.

“It doesn’t matter if you’re Choppy or Wade or myself,” shrugs Vandenbergh.

“Knowing they’ve seen these guys on TV, or knowing they just kick a football around, is an automatic engagement tool … they want to get out, kick a footy; but before we do that you’re going to do some education.”

On this trip, ‘Pauly’ is flanked by Pickett, former player Wade Thompson and a young Kaurna coordinator, Sasha de Kievit, who spent time with the club last year as an intern studying sports administration and was invited back as a graduate. She tells the kids her story embodies the dream of working in a football club – a dream that need not be just for the boys.

Thompson didn’t make a major mark in the AFL, but he left an impression with Vandenbergh, who asked him back as a Power Community ambassador. With WillPower’s expansion, that has now become a career.

Pauly runs the show; everyone else is here because he has chosen them. Pauly and Choppy go back a long way; Pickett’s wife Rebecca is Vandenbergh’s cousin. And while the journeyman’s departure from Port Adelaide just a year after being hailed a premiership hero was shrouded in bitterness, Vandenbergh believes bringing him back into the fold was significant.

“Not only because he’s passionate, but I think it’s important we look after our past greats too,” he says.

“He gave so much to us … it was pretty special in ’04, and he’ll always remember that.

“From where he came from, to achieve that with Gavin Wanganeen and the two Burgoynes … we were all so proud.”

Pickett is quietly satisfied with his lot – two flags, a Norm Smith and selection in the AFL’s Indigenous Team of the Century – but he believes “the proudest moment for most of the (indigenous) guys is getting drafted, I think”.

“I always went out and played not for myself but for my family,” he says, “my people.”

Vandenbergh believes the lack of access to services and support can entrench the notion for Aboriginal kids not to dream big dreams. Even finding a job seems out of reach to many, let along kicking the winner in an AFL final. Coming out to the west coast, time and again, with the likes of Pickett, Wanganeen and Peter Burgoyne, along with current stars like Chad Wingard and Paddy Ryder, helps make those dreams feel just a little more tangible.

The program teaches kids in remote indigenous communities about Aboriginal identity and how to live well: “Simple things like even getting the colours of the Aboriginal flag in the right order, or what the colours represent,” says Vandenbergh.

“They honestly have no knowledge like that … we drum into them, ‘Don’t take your culture for granted’, because if you’re not learning anything and you have kids and you don’t teach them anything, in three or four generations’ time there’s going to be nothing.”

This week’s lesson, though, is personal health: eating well, being active. Simple things. Dessert is a “sometimes food”. Play footy with friends instead of watching TV alone.

“They’re indigenous kids, but they’re kids – that’s number one,” Puccio tells me.

“These kids breathe, live, sleep football when the season comes, but they need to realise in a big country with just 18 teams, they’re not all going to be AFL players.

“You don’t know what the future is, but you’ve still got to get on with life.”

Confidence, determination are the watchwords, then; traits that don’t come easily even for those who have lived the dream.

“I did struggle a bit in my first year and a half (at North Melbourne) and I did come back home a few times,” Pickett admits.

“What made it easier for me at the Kangas was when they (traded in) Winston Abraham from Freo; he played a few years before me, with myself looking up to him as an older brother. He helped me along the way.”

In the late 1990s Pickett and Abraham were invited to an Aboriginal festival at Burunga in the Northern Territory. They flew up to Alice Springs and went by road along the Stuart Highway. Once there, the two premiership players inspired hero worship from the local kids; one father even asked Byron to pose for a snap with his young son. Many years later, the boy – now an adult – approached Pickett and showed him the photograph. He had forgotten it ever existed.

But the boy in the photograph, Jake Neade, hadn’t forgotten; he still has it even now, as a 21-year-old playing for Port Adelaide.

But the boy in the photograph, Jake Neade, hadn’t forgotten; he still has it even now, as a 21-year-old playing for Port Adelaide.

“Now he’s playing in the big time – it’s pretty surreal.” Pickett shakes his head.

“Makes me feel a little bit old.”

***

When Neade arrived at Port Adelaide, via a trade with Greater Western Sydney, he was just 18 and – at 170cm and a slight 67 kilos – the Power’s smallest listed player.

“We’d just drafted Oliver Wines (as well), and we took a group of the new players and Kenny (newly-arrived coach Ken Hinkley) and his assistants to spend three days here at Yalata,” Vandenbergh recalls.

“It was a little bit about Jake at the time, because Jake comes from such a remote community… I wanted Kenny to understand the challenges for some of these remote communities.

“You’ve got to understand the world here is quite different; the concept of time is quite different in remote communities.”

A far cry, indeed, from the regimented world of AFL clubs, wherein tardiness can see players dropped to the reserves, as befell Carlton’s Chris Yarran recently. The cultural divide became increasingly apparent as the Power convoy sped along the outback highway.

“They (Ken and the coaches) were getting so frustrated, because it was so far,” laughs Vandenbergh.

“We left Ceduna and I purposely didn’t tell them how far Yalata was; I kept saying: ‘Just over this hill, past these two trees…’ He was like, ‘how fucking long is this?!’ He was getting real frustrated by the time we got there.

“I said to Kenny: ‘What are youse in a rush for? We got no training, no meeting…this is what this lifestyle’s all about.’”

I imagine Hinkley responding in much the same way Peter Fonda’s character in Easy Rider did when confronted with similar sentiments while visiting a commune: “I’m hip about time. But I just gotta go…”

“They kind of struggle with it,” concedes Vandenbergh.

“But it’s just about seeing the smiles on these kids’ faces, and knowing from our club’s point of view we can make a difference by bringing non-Aboriginal players and coaches into their world.”

***

We leave Ceduna before first light for the two hour drive west to Yalata; as we pull up at a petrol station on the outskirts of town, a Nunga in a high-vis vest amiably extends his middle finger.

“That’s how they say ‘hello’ here,” Pauly jokes.

The man is his cousin. Pauly has a lot of cousins round these parts. In Aboriginal culture, essentially any relative of your own generation is your ‘cousin’.

Paul Vandenbergh is a gentle giant of a man who exudes a calm authority and a stoic wisdom; he quotes Gandhi, speaking of ‘being the change you wish to see’.

Most of the Nunga children call him ‘Uncle’: “They’re not even related, but that’s what they’re taught, respect for your elders,” he says, then scoffs at the notion he is “calling myself an elder” at 39. He stands six foot four; his sport was basketball. He only played football locally (“Ruck, of course!”)

Pauly hailed from Ceduna, and says: “My change came from my parents enforcing that education stuff”.

“I probably always talk about the sad part of them separating, but I don’t know what would have happened if they didn’t…if I’d still be here in Ceduna?”

His parents’ separation took him to Adelaide, “which at the time I thought was the worst thing in my life”.

He honed his social conscience over a decade at the Aboriginal Housing Authority (he tells me the average occupancy per dwelling in indigenous communities is 12). Jay Weatherill has courted him for a plum Upper House gig, but he has resisted ALP overtures thus far to remain at Port Adelaide, where since 2010 he has forged a powerful connection with indigenous communities; he is credited with helping sway Paddy Ryder to join the club, and the cause.

If you start losing language you start losing your culture. Imagine if a place like France just forgot French.

His mind seems constantly active, with matters big and small; “I’ve been trying to translate our club song into language,” he tells me, “but a lot of Aboriginal words don’t translate.” Specifically, ‘Power’ and ‘stop’, which seems a fundamental obstacle.

His family hailed from Maralinga; “I wouldn’t have a clue where my grandfather was born but it’s here somewhere,” he tells me on the road between Koonibba and Yalata. That was the Stolen Generation; Vandenbergh has learned that years later, his great-grandmother walked the 400 kilometres from Port Lincoln to Ceduna in search of her daughter; she stood at the fence of the school at Koonibba, but his grandmother no longer recognised her.

There are seven indigenous players on Port’s list – Brendon Ah Chee, Karl Amon, Jarman Impey, Jake Neade, Nathan Krakouer, Paddy Ryder and Chad Wingard – and Vandenbergh asserts that “all their families have gone through that, been through that policy”.

“Sorry Day is a really significant day for not just us, but it’s really significant too for all Australians, to help with the healing…celebrating that we don’t have policies like that any more.”

At a pitstop at the Nundroo Hotel/Motel, an off-the-beaten track locale miles from anywhere, a truckie calls out: “Ay, Pauly!” They chat for the next 15 minutes.

Another ‘cousin’?

“Nah, he’s family family. His name is Paul Miller…that’s my mother’s maiden name, Miller. So he’ll say to me, ‘Hey namesake!’

Every encounter has a story; that’s the way of things here.

Time finds it’s own rhythm. It is not, as the Prime Minister would have it, a lifestyle choice, but a way of life.

“We always talk about two worlds,” says Pauly, “two worlds coming together to create that piece in the middle, that third space.”

“How do we get every Australian into that third space, that grey space where two worlds come together?”

Even in football clubs, “there’s a hesitation or nervousness in investing in (indigenous players)”.

“Like anything, you want to know what you’re investing in, is it going to work out…reducing the risk,” muses Pauly.

“But we need a mindset of trying to get more people like Jake Neade into the system. They’re exciting, they’re raw, and they’re always crowd favourites; they bring people through the gates.”

It was when Choppy first arrived in South Australia, a similarly exciting, raw talent, that his and Pauly’s paths first crossed.

“We kind of grew up together,” recalls Vandenbergh.

“We’ve both got the same drive and passion to make a difference, I guess.”

Commuting from Port Lincoln to play with the Port Magpies on weekends, Byron would camp at Pauly’s Adelaide home; he was there when his proudest moment came.

“He was sitting in my house when his name got called for North Melbourne,” Vandenbergh says.

“No-one was there though. He was celebrating by himself.”

***

In some of the outback communities to which his work with the Power takes him, Wade Thompson is known as Kuru Mumoo.

The first part translates as ‘eyes’, the second somewhere between ‘ghost’ and ‘monster’.

“It’s kind of like ‘monster eyes’…it’s because of his green eyes,” Vandenbergh explains, referring to his protégé’s striking visage.

“That’s not really common (for indigenous people), especially in Aboriginal communities, so that’s his nickname to a lot of the remote communities.”

Now 27, Thompson could have been in the prime of an AFL career that never quite took off, cruelled by a glut of injuries and a dearth of opportunity.

Nonetheless, his story, told as he does the rounds from school to school, is an inspiring one: “I moved out of home when I was 15 years old, because I wanted to play AFL.”

“I knew I wasn’t going to get drafted in Port Augusta, so I did Year 12 over two years working part-time as a mentor at school.”

Wade is from the Adnyamathanya mob that hails from the Flinders Ranges. The tale of his leaving Port Augusta is certainly not embellished, but strategically redacted.

“I got kicked out of school, expelled for fighting,” he tells me sheepishly as he takes his turn in the driver’s seat, to the barely stifled mirth of his companions in the backseat.

Still, he displayed a striking determination to play football at the highest level, plying his wares in North Adelaide’s junior development squad before being picked up by the Power, his determination driven as much by what he didn’t want to become as by what he did.

“I see my father and that, he’s a bit of an alcoholic…I don’t want to be like him,” he says.

The determination is still evident. Thompson plays country footy in the Adelaide Plains; before we set off from Ceduna he had already run five kilometres along the foreshore, while I was wringing the last few seconds of sleep from a tight schedule.

There is an irony that his fortunes were so inextricably linked to Alberton.

“I barracked for Essendon most of my life,” he admits.

For years, he hated Port Adelaide for poaching his idol, Gavin Wanganeen, the Power’s inaugural captain.

It was a disdain he had to quickly put aside when he received the first of two phone calls that changes the course of his life.

“(It was) actually after my grandmother’s funeral, back out at one of my mates’ place,” he recalls.

“Chocko (then-Port coach Mark Williams) gave me a phone call and asked if I wanted to go to pre-season training.

“The funeral was in September and pre-season started in October (so) I said ‘I’ve got to have a few weeks off back here in Port Augusta (first)’.”

He belatedly joined training, but in the end, Thompson was by-passed in the preseason draft. Instead, Port picked him up months later as a rookie.

He kicked three goals in a 2009 pre-season game against Sydney, and played two senior games in his first year; but during the subsequent pre-season the errant elbow of teammate Marlon Motlop caught him in the face, fracturing his eye socket.

“I had to have surgery, and was out for 12 weeks,” he laments, a stint on the sidelines that he believes cruelled his senior career.

“I have a plate in my eye socket now,” he says.

While he was laid off, discovering the limitations of the rookie wage, he approached Port legend Russell Ebert about helping out with the club’s community youth program.

“I always wanted to give back to the community,” he says.

“There’s a sacrifice you have to make if you want to be something — not only an AFL player, but a leader in your community as well.”

He was delisted by Port after two years and worked as a carpenter, building portable houses.

The second phone call that changed his life came eight months later; it was Vandenbergh, asking if he wanted to work part-time as a Power community ambassador. Five years on, it’s a full-time career that sees him work side-by-side with his boyhood idol; Wanganeen, the Essendon Brownlow medallist, is a fellow WillPower ambassador.

“I actually told him on our last trip to the APY Lands (that) him and Byron were my favourites,” Thompson admits self-consciously.

“I told him I wanted to be magic like him and tackle and bump like Byron.”

***

On the second night, Shannon – one of Pauly’s many cousins – joins us for dinner. He says little, but enlivens the gathering with his distinctive laugh, a contagious Kerry O’Keefe whinny that inadvertently invites those gathered to be as humorous as possible, just to hear it. Hence his nickname: “Giggles.”

I’m told Giggles’s other claim to fame was cleaning up the brother of Crows premiership captain Mark Bickley in a country league game many years ago.

If hardness is a trait sought after in football, there seems a certain ferocity bred in regional communities that is worn as badge of considerable pride.

Choppy Pickett came harder than most.

“My Mum gave me that nickname as a child, because I used to watch Bruce Lee movies and go round karate chopping all the other kids,” he explains.

“I’m glad it came from my Mum and not my mates; any nickname from your mates is usually something stupid.”

As he honed his skills, he graduated from karate chops to full-throttle shirt-fronts. The likes of Darren Milburn, Brendan Krummel, Tadgh Kennelly, Kane Cornes, Simon Wiggins, Rhett Biglands and James Begley left the field on stretchers or nursing serious injuries after copping the brunt of Byron’s notorious bumps, however he was rarely suspended for such incidents. He straddled a line, but rarely crossed it.

In 2003, the premiership coach and respected commentator Robert Walls labelled him a “tragic figure”, after the Port recruit took out two Demons players, Nathan Brown and Simon Godfrey, during a single game. Walls called him “Byron the Baddie”, warning he had “built a reputation that now haunts him”.

“He now too often takes his eyes off the ball,” he wrote.

“He has given up on the one-percenters, the tackles, chases and smothers. You wonder why Port took him on.”

The following season, Pickett was named best on ground as the Power won its inaugural AFL flag.

Even now, the ‘Bad-boy Byron’ tag is a millstone that hangs easily around his neck alongside his September medallions.

“I like being remembered for that (hardness), but I kicked some goals over the years as well,” he tells me.

His was a style forged from family roots.

“Growing up, I used to watch my father, Byron Snr, and my uncles…they played the same style of footy; hard footy.

“I learnt off them.”

With wife Rebecca, he has two sons of his own, 10-year-old Byron Jr and Kayde, 8, along with three older daughters: Lakeesha, Shawanah and Mikayla, who turns 18 in December.

“I just hope all my kids – not just my sons, but the girls as well – look at my achievements and what sacrifices I had to make to get there,” he says.

But while he was homesick leaving family and friends to pursue football in Melbourne with the Kangaroos, he reflects on a perverse positive: “I would have had too much family (here); I would’ve got sidetracked.”

I ask him whether that was what happened late in his tenure with Port Adelaide; when the premiership celebrations had died down, he literally ran into controversy when he drunkenly steered a car through the brick wall of a Port Augusta home.

It’s not an incident he volunteers to discuss.

“I think I struggled to get into the game (in my last year at Port),” he ventures instead.

Pauly suggests another issue that got his friend offside with the Power hierarchy: Pickett’s frequent visits back to Port Lincoln and WA for family funerals. He would tell the club he had to attend his grandfather’s funeral, a line that to the training-oriented management team sounded increasingly like a ‘dog ate my homework’ excuse.

Vandenbergh recalls one-time Western Bulldogs coach Peter Rohde, later Port’s football operations manager, remarking that “we always thought Byron was lying to us”.

“His mentality was, ‘look, you’ve run out of grandparents!’”

In reality, though, the episode suggests a simple disconnect between cultures, and suggests how easy it could have been to rectify.

“My grandfather is the eldest of 11,” explains Vandenbergh, “so essentially, I had 11 grandparents.”

“In the eyes of Aboriginal communities, funerals are the number one priority.

“That probably was a little part of the demise of Byron at Port Adelaide, because they thought he was always going away to funerals, and they thought he was lying to the club about who had passed away.”

In any case, the demise came.

As Pickett recalls: “Obviously when you do that too long, when you’re too inconsistent, it’s always in the back of players’ minds when they reach a certain age, that they might be traded.”

And so, two years after he drew the ire of Robert Walls by flattening two Melbourne players, Pickett joined them as teammates.

I’m a football man…I love everything it stands for.

He didn’t consider it a disappointing finish: he played finals in his first season there, and while he fell foul of injury niggles and disciplinary issues he still displayed some of the old Choppy spark.

It was his old mate Pauly who brought him back to the fold.

“It’s always good to be a part of the club I played with,” Pickett admits, clearly more at ease in Alberton’s confines now than he was when he learnt his manager had agreed to a trade at the end of 2005, while he was away visiting family in WA.

“Ever since Paul’s been at the club it’s changed dramatically, I think,” he says.

“The way the club thinks on the aspects of Aboriginal lifestyle, that you sometimes have to leave footy to come home for funerals…

“They were just confused, I think; the footy community at that time was probably thinking ‘he went to his grandfather’s funeral a couple of months ago’, but us Aboriginals, we’ve got more than one grandmother and grandfather…That’s the respect we’ve got for our elders.”

***

One of the sparkling soliloquies in Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction that has found its way into popular culture’s collective subconscious came when Uma Thurman’s Mia Wallace mused about “uncomfortable silences”.

“Why do we feel it’s necessary to yak about bullshit in order to be comfortable?” she pondered, insisting “you know you’ve found somebody special when you can just shut the fuck up for a minute and comfortably enjoy the silence”.

Comfortable silence is a familiar concept in the indigenous world.

As he steers us toward Yalata, his companions sleeping quietly in the back seat, Vandenbergh explains that there is a certain cultural shyness. “If it was just myself, Choppy and Wade in the car today, we could have sat there and not said a word,” he tells me.

Rohde, Vandenbergh says, was briefly a teacher, and when he had Aboriginal children in his class he got frustrated because they wouldn’t look him in the eyes.

“That’s a cultural thing: you shouldn’t look people in the eyes, it’s an aggressive thing,” he says.

“It’s a shyness, a shame as well.”

By Vandenbergh’s reckoning, much of the cultural divide comes down to simple concepts, such as the fact there’s no Aboriginal words for ‘please’ or ‘thank-you’. He says more than three quarters of indigenous kids have a hearing problem.

“I was deaf growing up in Ceduna; Wade’s son, who’s two, has been in hospital three times.

“I don’t know why it happens.”

As we approach Yalata, he predicts that “this group will be quiet initially as well”.

“But as soon as we’re outside they’ll be hanging off us.”

***

The burly kid sits with a glare fixed on his face. Pauly knows him by name, but we’ll call him Brock.

The Yalata kids are seated in a weatherboard library; the usual young readers’ books pack the shelves at the back of the room. On the walls, pictures of native animals are accompanied by their names in two languages: ‘Patilpa – Port Lincoln Parrot’, ‘Tjintir-tjinrirpa – Willy Wagtail’, ‘Papa Inura – Dingo’.

A scuffed maroon leather couch sits in front of a whiteboard at the front of the room, under the glare of a large flatscreen TV.

Brock is restless.

As Sasha asks the group for a show of hands on ‘Who had breakfast this morning’, he walks past her and flops himself down on the couch.

Several hands go up in the affirmative.

‘What did you have? Weet-bix? Weet-bix!’

I sit at the back of the classroom, the proverbial fly on the wall. Vandenbergh perches beside me and deconstructs the emerging scenario with practiced confidence; he has seen it all before.

“You see that kid on the couch,” he gestures.

I watch him. Pauly says it’s the ones like Brock that keep them coming back, even though it’s a victory that he’s even turned up for this session.

“He’ll get up and walk out before we finish,” Vandenbergh asserts matter-of-factly.

Yalata Anangu School is perched on the corner of two unsealed dirt roads, Old Oak Valley Road and Watu St. As we pull up, dust billowing in our stride, Vandenbergh assures me: “You’ll see the difference today, with the numeracy and literacy levels…that’s what our challenge is.”

If there was reticence with the children at Crossways and Ceduna, at Yalata it is more like brinkmanship.

“They don’t want to answer a question,” Vandenbergh whispers.

“They won’t say something, because they (think they’ll) almost get paid out, get laughed at…and they’ll go back in their shell again and say ‘I’m not going to say anything next time’.”

He says these simple questions of diet and exercise habits are often greeted by blank looks, but “if there’s an Anangu education worker in the classroom translating, they’ll get it”.

“As soon as someone translates, they’ll respond. Numeracy and literacy levels are real low, but it’s because English is their second language.”

The WillPower ambassadors have begun a Pitjantjatjara language course. It’s tough going but Vandenbergh believes it will be a powerful tool, “a real big step towards some kind of connection in their language”.

Sasha tells children to write their name on their work, followed by “your mob”, or if they don’t know their mob, “where you come from”.

“Some of us are still on our journey,” she reassures them.

“Most people refer to themselves by what language group they come from, what country,” Vandenbergh explains.

“But because my language is totally different to what Wade speaks, we call ourselves Aboriginal people.”

Indigenous language is diffuse and fragile; like many an endangered species, it is dying because it does not reproduce. Different mobs, different tribes, have learned to speak in different tongues, and these are passed down verbally. Nothing is written.

“It’s not healthy,” Pauly laments.

“If you start losing language you start losing your culture, you know… Imagine if a place like France just forgot French. That would be sad.”

Of the four schools we visit, only Yalata forbids me taking photographs. The school has no oval as such, but a concrete quadrangle protected by imposing shade sails, under which bare-footed children kick footballs with carefree zeal.

Most of the footballs, faded and cracked, bear Port Power logos, remnants of past WillPower visits.

If there was a strong show of hands for those who had eaten that morning, it might be due to a program that provides free breakfast to students before class.

There were 24 takers today; the day before, the Tuesday after the Queen’s Birthday long weekend, there were 30.

“It’s always difficult after a long weekend,” says Murray Tumes, a permanent relief teacher working between Oak Valley and Yalata.

He says many families in Yalata only plan one day at a time, even for meals, and many get caught short when the general store is closed.

Tumes moved here from Victor Harbor “to fill in for teachers that are sick”, while his wife stayed on to care for her ailing 97-year-old father.

“It works out well for us,” he tells me.

“The Government provides me a car to go between the two schools…there’s a teacher that left here two weeks ago, so I’m taking his place.”

He’s 68 years old, and started teaching in ’67, so “I’ve taught quite a few years”.

This is his 22nd school, but “I’ve only been teaching Aboriginal kids for four years”.

Tumes works in the local Lutheran church, which he says about half the community attends.

“The pastor’s an indigenous guy who does a really good job with his wife,” he says.

He says some Yalata teens move away to Adelaide, staying in dedicated campuses such as Northgate’s Wiltja, but many encounter problems and come back.

“Homesickness is a big problem, not being able to fit in to Adelaide society…the structures of high-schools are very difficult for them,” he says.

“I reckon you’d get 50 per cent that would go through, then they come back here…and what do they do after that?

“There’s not much to do really for them at Yalata.”

Unemployment is near-universal: “There’s a lot of young people that just walk around in the afternoon.”

“There are problems with the community as far as alcohol goes in there, and drugs, though I’ve got no firsthand knowledge of it.”

Tumes enthuses about Sasha’s presence, “for the girls…they respond really well to her”.

He points out a female student, maybe 16, who stands quietly, attentively, as the children play.

“She could do really well,” he says.

“She helps the teachers; she’d be great in a kindy or reception class. So they can move into that or go into the shop…” He gestures up the road towards the lone convenience store.

“But not much more.”

A few days before we arrive in Yalata, a 17-year-old boy was charged over the alleged stabbing murder of his partner.

“Domestic violence is a real problem,” says Tumes.

“We’ve always got to be mindful of the fact the girls will be picked on.”

He stands quietly for a moment, watching the children play. A ball sails onto the tin roof of the gymnasium and a shirtless boy, no more than ten, quickly scrambles up to retrieve it.

“But it’s a happy community nonetheless,” Tumes nods.

Vandenbergh concurs.

“It’s amazing how happy these kids are,” he tells me.

“Some of these kids won’t even have a shirt on their back while they’re sitting in class, or shoes.

“But they’re happy as, you know.”

Later the group will decamp to a makeshift oval nearby, a dustbowl the size of a basketball court, littered with empty plastic bottles and other detritus, with fence posts for makeshift goals through which balls sail like missiles, clattering loudly into the wire fence behind.

Three stray dogs fight amongst themselves, oblivious to the frenetic activity around them, as hordes of children run and crash this way and that, tackling fiercely.

Some are tall, others tiny; Tumes reckons their ages would range anywhere from 6 to 14 years, but this contest is one in, all in. Here on the gravelly field of play, this is where children too shy to raise their hand in class can make their mark.

“One boy here can do 20 backflips on a trampoline,” the relief teacher enthuses.

“I’ve seen him do it! And the girls can throw like boys.”

We always talk about two worlds, coming together to create that piece in the middle, that third space. How do we get every Australian into that that grey space where two worlds come together?

Perhaps it’s that unnaturally-bridled energy that bubbles over in the classroom. As the healthy eating information session continues, disorder ripples through the room like a virus.

Wade Thompson, those glassy-green eyes showing a hint of anxiety, suggests the class might like to “draw a picture of yourself kicking a goal or taking a screamer, enjoying yourself”.

Some children do. One, instead, crouches by my feet at the back of the room and busies himself with a box of Lego. He holds up the fruit of his labour with a shy flourish, urging me to approve the simple construction: two doors, two windows.

“That’s my house,” he assures me in a whispered squeak.

“See?” Pauly nods, unsurprised. “Kind of lost them…”

Sensing the communal attention lapse, Thompson peruses the remainder of his notes.

“We’re going to skip the rest of it, because I think we’re starting to lose you,” he admits.

He turns to the back page, a crossword with clues devoted to healthy lifestyle.

“They love this one,” Pauly assures me.

A tentative silence descends again, as Sasha gratefully thanks “those people up the front looking, and showing me you’re ready to listen”.

Mini-footballs sporting the Power colours will be handed out to those who find the most hidden words. Suddenly desperate, the boy with the Lego fetches his booklet and returns to me, thrusting it in my direction.

“Find a word,” he quietly demands.

I nervously look around me, unclear as to my appropriate response. I hesitate, then circle the first word I see: “Toothpaste”.

I hand back the paper: “There you go”, but he refuses to accept it.

“Put lots please.”

He is not for dissuading, so I circle a few more words: Fluoride, Fruit, Gums, Vegetables…

At the front of the room, Thompson is calling for the papers to be returned.

“Quickly,” the boy urges.

I end up helping him up to 16 words, and he trots off mildly satisfied. I don’t know whether it’s enough to win him a football, although I later see him brandishing one; he borrows my pen to mark it as his own.

Around the time Sasha asks the class “Who watches TV when you get home?” Brock stands and walks out.

***

It’s still anathema for Ron Redford to get about Ceduna in Port Adelaide colours, but that is what he’s paid to do.

He describes himself as a “free agent”. A player for Glenelg in the 1960s, Redford is an old-school football ‘personality’, a former president of the Far West Football League, lately employed by the SANFL.

“My magnificent job title is Far West Programs Co-ordinator,” he beams.

Redford likes a yarn, and has a kitbag full of war stories, like the time in his playing days when he approached an anonymous “strongly-built centreline/half-forward-line player for Port Adelaide” to offer a sportsmanlike pre-match handshake.

As Redford tells it, the Magpie man “made sure he had the crowd watching” before pointedly spitting on the ground in front of him, and theatrically turning to bask in the approbation of the Port faithful.

But, Redford admits, “we all had the greatest admiration for Port, and I still do”.

“I just wish Glenelg could be like them,” he laments, “but we have some problem doing that.”

Redford was overseeing the local rollout of the Government “Breaking the Cycle” program when Port Adelaide appointed him as their local ‘go-to’ man.

“Russell Ebert starts laughing whenever I walk into Alberton with the Port gear on,” he smirks.

Ron’s gig has him delivering AusKick programs and preaching the WillPower gospel: “I make sure when arrangements are made, everybody knows who’s doing what, what time they’re there and what’s expected of them.”

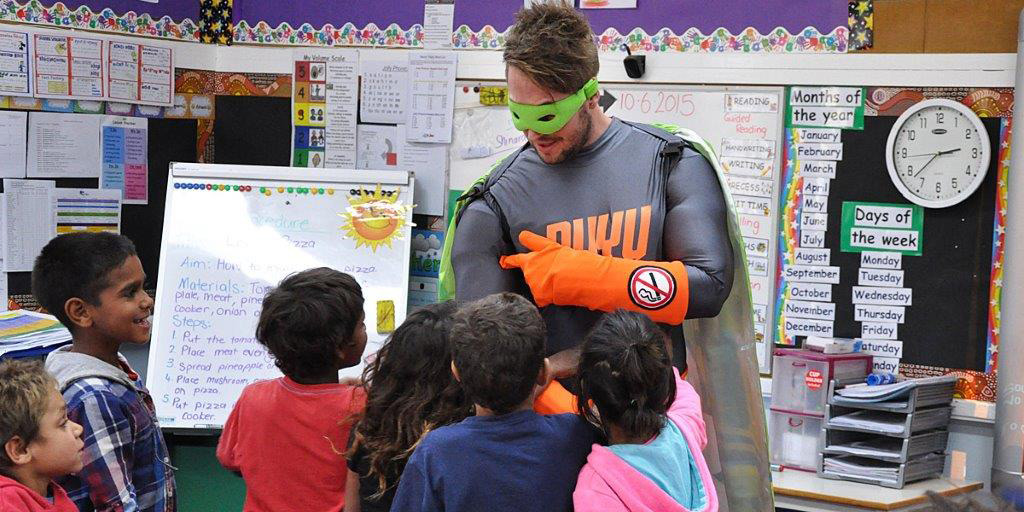

It’s not always as easy as it sounds; today, the WillPower ambassadors’ visit to Koonibba Aboriginal School will coincide with a whistlestop by the SA Aboriginal Health Council’s resident ‘superhero’, Puyu Blaster, a caped crusader against youth smoking.

In the classroom, the smiling visage of Chad Wingard adorns the classroom wall, in a poster telling children the “Brush Twice Daily”.

“That’s my little brother,” the man in the Puyu Blaster suit sheepishly smiles. Chad may kick the freakish goals, but today Trent Wingard is the king of the kids.

Koonibba is a mainstay of the Far West League; the local team, the Roosters, are reigning champions. Like everywhere else along the west coast, football is not merely an escape, but a creed.

“These kids are very easy to please,” says Redford.

“All they want is somebody to take some notice of them and be interested in them, so it’s beneficial that every kid up here loves AFL. Port has seven well-regarded indigenous players on their team and these kids fall over themselves to reach out and touch them.”

It’s not just hero-worship, but a desire to realise the tangible prospect of a future beyond what they see every day.

“All they know is their community life,” says Redford.

“They know there’s opportunities out there, but many of them struggle to read and write correctly…these people don’t want to move off their communities to go and get jobs like that.

“We need to be finding something for them within their own communities.”

Redford stands before the class, preaching “Ronny’s Rules”, his three commandments for today, and every day after: watch the ball; have fun; stay in school.

“I talk purely and simply on the basis of what’s right for them and how to live their life in a healthy fashion,” he says.

“In football, you don’t exist if you’re a cheat or a liar, if you don’t look after your body and you’re not part of team culture.

“That’s really important, the disciplines it teaches you as a person.”

And every now and then, he concedes, “I weave in a Glenelg story as well”.

He smiles a craggy smile. “I’m a football man,” he says.

“I love everything it stands for.”

***

The Port Adelaide ambassadors stop for lunch at the Yalata General Store before heading off for Koonibba, when Sasha poses a question to Pauly: “What’s the most important thing to get across to the WillPower students?”

“Is it just the course content, or is it that we’re supporting them, and keep coming back? Or just that we’re here?”

The mentor thinks it over.

“Ultimately we want to have an impact in the classroom,” he decides.

“We’re telling them, ‘we don’t want you to leave your community but you can come to Adelaide and get all the skills you need to come back and make your community strong’.”

Later, he tells me the classroom time is really “all about reflection”.

“I’m definitely not saying we can do it all; our strength is being in the classroom and getting kids to think about education and being healthy…but there always seems to be a bigger thing at play, you know?

“Like anywhere, not just from an Aboriginal point of view, communities still need good strong leaders. They’ve got some great elders at Yalata, but there has to be that succession…

“You just never know the impact you can have on an individual kids, you know?”

Just ask Jake Neade.

As we begin our journey back east down the dirt track, one of the Yalata kids emerges from the store. It is lunchtime. He carries a bottle of Fanta and a packet of chips.

***

“There was a great coach in the ‘50s that came over from St Kilda to coach Norwood called Alan Killigrew.”

Ron Redford is in typically philosophical form as he hammers makeshift goalposts into the ground. Koonibba Area School only has one set of permanent goalposts at the far end of its oval, and Pauly has asked him to provide a second set.

“Killigrew was one of the hot gospellers of football,” he puffs, “great talker, great concepts.”

He fixes the first behind-post into position, then moves onto the next, rarely pausing for breath as he recounts his tale.

Short-statured but high-minded, Killigrew finished his senior coaching career in Perth mentoring Subiaco, a powerhouse of the then-WANFL, with his combination of football nous and homespun philosophy.

Redford recalls that the Victorian wrestled with the concept of football’s role in the lives of his charges.

“’People ask me ‘What does football do for you’, and I could never, ever give an answer’,” he remembers Killigrew telling him many years earlier.

“’But one day I was sitting on the West Australian coast…West of Western Australia is nothing except the Roaring Forties…’” Redford gestures dramatically with a mallet-clenching fist, emulating the fiery oratory of his subject, “…that rip through with astounding power, until they reach South Africa.

“’And then, watching the trees along the coastline, I realised what football does for you.

“’Those trees were bent over by prevailing forces, because there was nothing to stop them.

“’But had they been staked, they’d be standing tall. And that’s what Australian Football does for kids…

“’It provides the stake that makes them grow straight and tall.’”

Redford stands silently for a moment, then continues to pound his own stake into the dry outback dirt.