What the Australian media could learn from the French

The ABC favouring balance over knowledge, commercial media elevating uninformed opinion, the seeking of heat instead of light – the Australian media’s standards would not be tolerated in France, argues Dominic Stefanson.

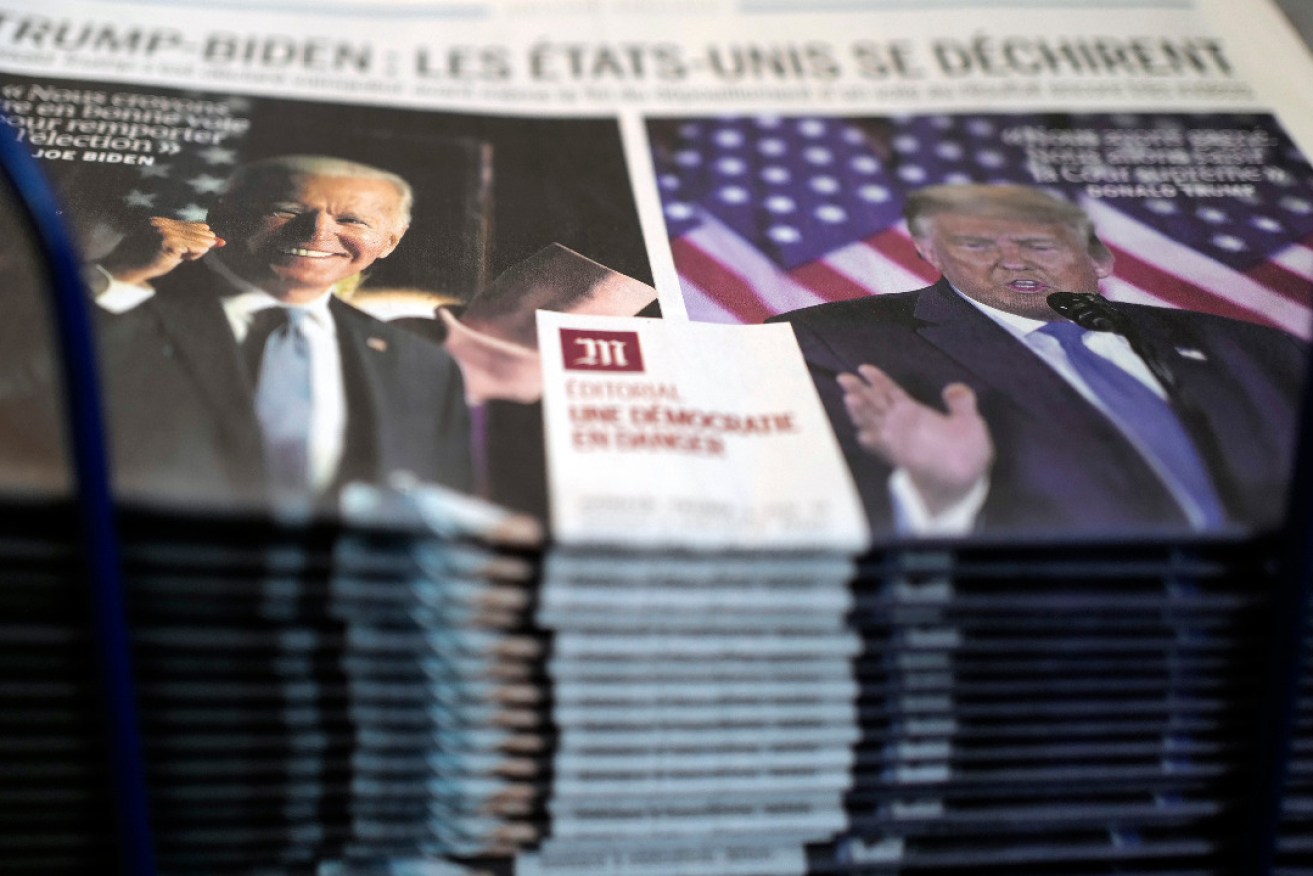

A stack of the French newspaper Le Monde on a newsstand in Paris. Photo: Francois Mori/AP

I returned to France late last year after many years and I was struck by how deeply the French remain committed to Enlightenment ideals of reason, logic and objective truths.

It is a defining national characteristic and impacts many facets of life in France, but is particularly noticeable in how French media reports the news.

More about media later, but first to understand the Enlightenment and how it still permeates French life.

The ideals of the Enlightenment were best captured in the publication of the Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts) between 1751-1772.

Led by the playwright Diderot and the mathematician D’Alembert and including Voltaire, Rosseau, Buffon and Montesquieu alongside many relative unknowns, the encyclopédistes, as the 100 or so contributing authors came to be known, set about describing and illustrating all human knowledge in one book.

In the end, the encyclopedia was 28 volumes (including illustrations) and included topics such as the sciences, math, military studies, philosophy, architecture, religion, geography, astronomy and professions, including, as is often noted, beekeeping. It was the first modern encyclopedia and endeavoured to be a single source of all knowledge. Quelle audace!

The encyclopédistes believed in knowledge: right and wrong, truth and falsehood. They also believed that human life, both individually and collectively, would be improved by the possession and application of knowledge.

The spirit of the encyclopédistes is alive and well in France and can be found in many aspects of day-to-day life where there is a right and a wrong, as in an incorrect way to do things. Let me give two examples: eating oysters and buying shoes.

In Cancale, a small coastal village in Brittany near the Mont-Saint-Michel, the fortified monastery which becomes an island depending on very large and rapid tidal movements, there is a marché aux huîtres, an oyster market where local producers come together to sell oysters on the foreshore. You can buy a degustation of different style oysters. It is all very picturesque and well worth a visit. These oysters benefit from the large tidal movements and are the best in the world. For the oyster farmers on the foreshore, this not an opinion but an objective fact.

The author with his oyster degustation, near Mont-Saint-Michel in France.

When purchasing the tasting plate, you receive very specific instructions on the order in which they should be eaten and which oysters need to be eaten with lemon and which without. There is a right and a wrong way of doing these things. My tasting plate, consumed as per instruction, tasted great. Incidentally, the final oyster, the largest and plumpest was “l’Australienne” and tasted similar to a Coffin Bay oyster.

The next day I bought a pair of shoes in the nearby mediaeval market town of Dinan which can be accessed by riverboat, again all painfully picturesque and worth a visit. Anyway, in the shoe shop, I was hesitating between a size 43 and 44. The sales assistant did not ask me which felt more comfortable. This was not a matter of opinion. She felt my foot and I was informed that size 43 was la taile correcte – the correct size. She fits a lot more shoes than I do, so I went with 43 and it turned out ok.

There is a correct size for my shoe and a correct way to eat oysters. For many foods and wines, the correct way is legislated. See, for example, the bread law of September 13, 1993 (Décret n° 93-1074), updating the 1905 law which regulates how a baguette should be made and stored before sale.

A “new world” Australian or American mindset might see this as overly restrictive and stifling. The French part of me does not care because the bread (and cheese and wine) is better. And, I don’t think, I know.

It also helps to explain why the French get so upset when someone on the other side of the earth sells a floppy bread stick and tasteless cheese as a baguette and camembert.

Alongside a belief in true and false as it relates to food (and everything else), the encyclopédistes also believed society would be improved if more people gained knowledge – a democratisation of knowledge so to speak. This belief in the benefits of knowledge persists in France today. The French like to be informed.

News and current affairs, known as programmes d’informations et d’actualités, dominate French free-to-air television, publications and social media sites.

Two issues covered while I was in France were the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan and the Hamas attacks on Israel on October 7.

It was fascinating to see how these topics were handled. A guest or a panellist on a French current affairs show will be someone who has a claim to knowledge and expertise on the issue: maybe a history professor or academic who has written books on the topic, or maybe a former diplomat or a famous author from the country. In short, someone who knows the topic. The program will seek to uncover and explain why there is a conflict and identify who is in the right and wrong and perhaps even look at potential remedies. The purpose is to seek the truth and separate facts from opinions.

It is, of course, hard to distinguish between the objective and subjective on such complex topics. This was true of the encyclopédistes who would often promote certain political or philosophical viewpoints in their articles. However, expertise and knowledge were and are the starting point and the foundation of any opinion.

French news shows have no space for American-style “alternative facts” nor the opinions and fantasies that flow on from them.

Australian media seems to be heading more towards the American than the French approach and we are often provided opinions without knowledge.

This happens for a variety of reasons. The ABC prioritises balance over knowledge, maybe in response to continual attacks about bias. A panel on the ABC will feature people on both sides of an argument – maybe someone from a Jewish association counter-positioned to someone representing the Palestinian position. And on just about any topic of conversation there will be a person connected to the Labor Party and another to the Liberal Party. A panel will need a female and male panellist, perhaps someone non-binary, someone old and young.

To avoid bias, all voices are then given equal time, even if some are clearly talking bullshit (a frequent occurrence when the topic is climate change and electricity markets). The end result is a lot of people pontificating on matters they don’t know much about. It is boring and it is not informative.

The same thing happens in commercial media, where often two sides of an argument are given equal time with no consideration given to the facts of the matter. I suspect this is in part because there are too few journalists left to fill up so much space. It is easy to recount well-worn positions. Unfortunately, there is no net knowledge gain by the audience.

A lack of time or desire to uncover the truth also leads to gross oversimplification. Why bother examining the fiscal, economic and social impact of taxation changes when you can just speculate about the impact of the PM lying?

Some news and current affairs jump straight into uninformed opinion and then report it as fact. Quelle horreur!

Whatever the causes, we, the audience, are left with unsubstantiated and uninformed opinions – really the most useless thing in the world.

Dr Dominic Stefanson is a French Australian who has a thirst for knowledge and a lot of opinions. Dominic works in his own consultancy company, based in Adelaide.