It’s not journalists’ questions that are unfair to Nicola Spurrier

It isn’t unfair for journalists to ask the tough questions about the state’s COVID-19 response – but there is a problem in the government presenting an unelected public servant as the ultimate word on every policy response, argues Kevin Naughton.

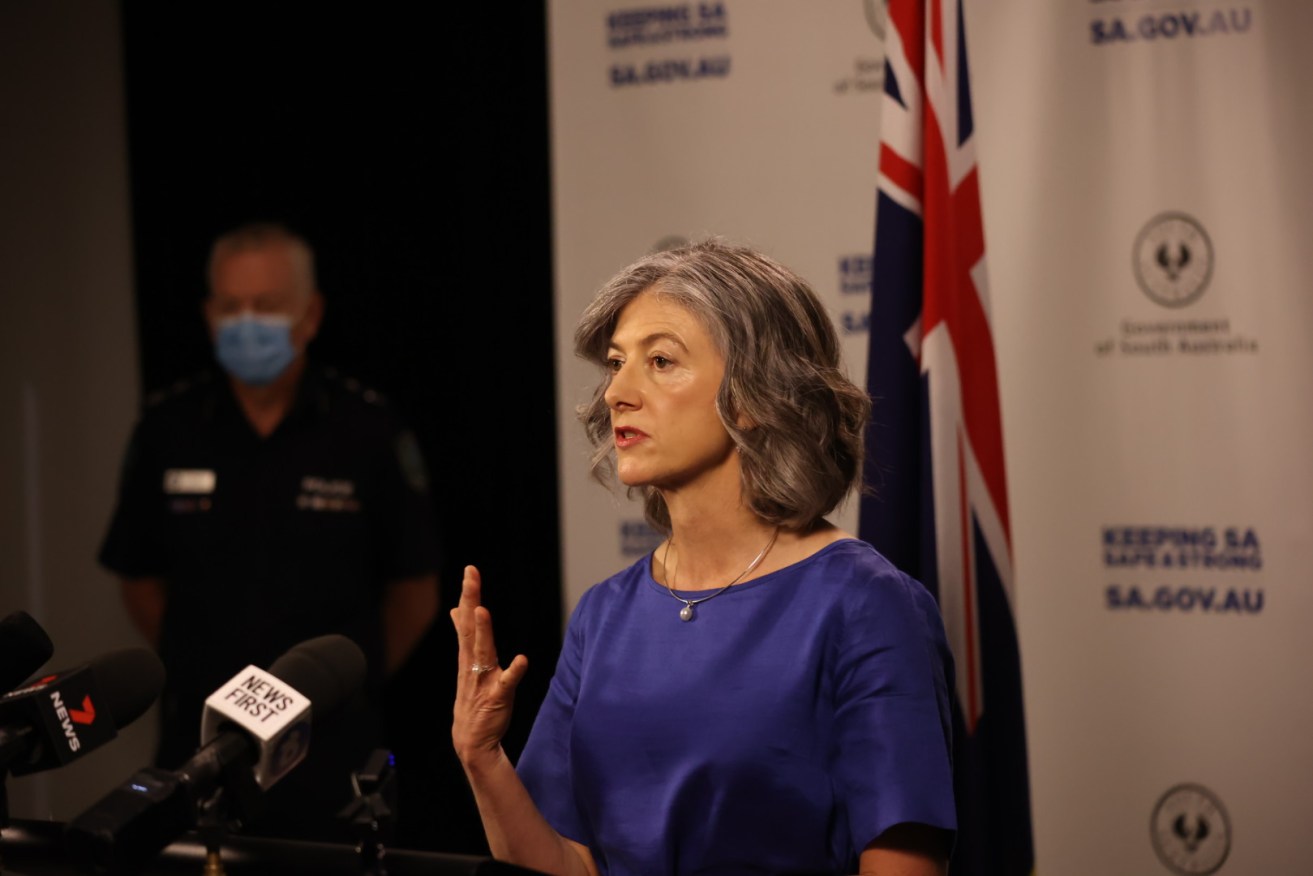

Nicola Spurrier is a clear communicator and a hard worker, but to present her as a "saint" is unfair. Photo: Tony Lewis/InDaily

The text message reply from one of Adelaide’s most respected journalists was disconcerting: “No bastard wants to be seen to be attacking Nicola.”

It was a response to my observation that bureaucracies are adept at ring-fencing their mistakes and how sad it was that journalists were being shut down, criticised or ignored when seeking information regarding the pizza-inspired lockdown of the entire state.

The shutdown was based on “the health advice”, the Premier Steven Marshall said, as did the Police Commissioner.

When that advice changed, the media wanted to know when, how, why, who etc.

Chief Public Health Officer Professor Nicola Spurrier would not be drawn on whether a mistake had been made in checking the story of a confirmed case who appeared to have been infected via a pizza box. The Premier also avoided the issue of cross-checking, preferring the more dramatic view that he was “fuming” at what he described as a lie told by a pizza shop worker.

That was Friday – one short and very long week ago.

By Monday, the defence of the shutdown was even more strident.

Professor Spurrier did not respond to ABC Radio presenter Ali Clarke’s question about whether or not the pizza story had been cross-checked via receipts, travel records, a second person to verify or mobile phone location services. Instead, she repeated her line that we had averted a second wave.

The Premier stuck to the same message telling national television programs that “you only get one chance to stop a second wave”. Nationally, other infectious disease experts weren’t buying the South Australian line.

The ABC’s Ali Clarke, meanwhile, revealed to listeners she was getting text messages while still on the air, attacking her for asking tough questions of the Chief Public Health Officer. No wonder, because Professor Spurrier was being used daily as the State Government’s reference point of absolute truth and power.

But the media was getting edgy about the infallibility of the State Government’s shield.

What sparked the media curiosity was the revelation last Friday by Police Commissioner Grant Stevens that police had ascertained that the Woodville pizza story didn’t stack up. When a review team was sent to re-interview the man, later revealed as a Spanish national here on a graduates visa, the premise on which the lockdown was based fell apart, he said.

The sure and steady Commissioner appeared none-too-impressed with the health blunder, but he didn’t seek to throw direct blame, instead assembling a taskforce to examine what went wrong.

That same day, when journalists started questioning Professor Spurrier about the possibility of a blunder they were redirected to the heroic story of a young doctor who had taken a respiratory swab from a patient and discovered the first case in the Parafield cluster. The same doctor was made available to The Advertiser and then morning radio. Not so, however, the contact tracer who missed a key part of the pizza worker’s movements. That part of the story is likely to be sealed and put away and the worker never mentioned.

The Premier did, however, find time again to say he was “fuming” at the deceit of the pizza worker. The classic political strategy of “sharing the rage” was in full view as the pizza shop and its employee became villains.

Yet there remain a lot of unanswered questions and it is the media’s role to continue to seek answers, even if they are targeted for daring to query the person promoted by the State Government as its source of unquestioned advice – a bureaucratic saint.

It is still not clear why a shutdown was ordered based on one piece of data that was not tested or cross-checked. What was the Police Commissioner’s reaction it became apparent the story didn’t stack up, and his officers had to re-interview the pizza worker? Is there a conflict between two of the three key decision-makers?

What was the basis for Professor Spurrier indicating that this cluster is from a particularly “sneaky” strain of COVID-19, a claim dismissed by a number of prominent senior medical specialists? Is this statement now wrong? If so, has it been corrected?

Why did SA Health believe – at least for a time – that the virus survived and travelled on a pizza box when such a view is contrary to medical evidence from around the world? Exactly what steps will be taken in the future to cross-check unusual propositions such as the pizza contamination assumption?

Will anyone put their hand up to say “we made a mistake” and apologise? That alone might take the heat out of this story and counter the now widespread confusion in the community.

But correcting mistakes doesn’t appear to be high on the priority list in the management of this pandemic.

Remember the baggage handlers’ outbreak at Adelaide Airport?

We were told to clean our luggage and Qantas and the Airport were put in the frame for their hygiene practices.

An SA Health source told me that the outbreak was later traced to an infected and symptomatic worker going to work and passing it on the other workers – not from contaminated luggage or any other source.

Does SA Health need to make an adjustment to that part of the story?

And then there was the Tanunda cluster – what happened with the disappearing USA touring couple? How did they skip quarantine?

By Monday last week, the Premier’s Liberal Party colleague Nick McBride MP was on the attack, unwilling to play the game of convincing us that we had just avoided a calamity. He said a mistake had been made.

By Monday, the Premier had conceded that the Parafield cluster was contained with every case tracked to a known source.

Yet also on Monday, Professor Spurrier was still adamant that there had been no time to pause and check the pizza concept and there were no regrets. Businesses and stood-down workers, however, had plenty of regrets. The doubt now underpins widespread falls in business activity.

And also last week, questions were being asked interstate that need to be answered by SA Health, given that the “evidence was slim for the theories used to initially justify an unprecedented lockdown”.

Four days later, a new case connected to the same pizza bar was met by a different response. Again, the Premier and his government deferred to “the health advice”.

That advice comes via a Chief Public Health Officer promoted by government PR machines as saintly.

They have ridden on the back of Professor Spurrier’s flawless reputation, based on her clarity of communication, dedication to public health and extreme work ethic. It’s a reputation well-deserved. But a health officer cannot carry the burden of broad social and economic outcomes. That is the job of an elected Premier, his Health Minister and Cabinet members.

It’s also an unfair burden for Nicola Spurrier that she is promoted as perfect and bestowed quasi-sainthood.

It’s time the Premier took the front stage and the responsibility and Professor Spurrier resumed the role of adviser to government. It’s the model used by every other state Premier, based on the concept that they are elected by the people and are responsible to the parliament.

The fact that some of our top journalists are being targeted for asking questions that are fair, reasonable and necessary is not a healthy sign.

There is never any reason to fear the truth, because cover-ups never end well.

Don’t assume that any bureaucrat is a saint and cannot be questioned; nor should we assume that anyone is immune from error.

If journalists are asking difficult questions, it’s because the integrity of our health system could be at stake.

Don’t ask, don’t discover.

Kevin Naughton is a former senior journalist and broadcaster. He was a political adviser to Martin Hamilton-Smith as Liberal leader and as a minister in the Weatherill Cabinet, as well as Labor leader Peter Malinauskas.