Richardson: The new challenge to the politics of complacency

The stunning near-success of Jeremy Corbyn in the UK has more in common with the rise of Donald Trump than the Left would like to admit. Tom Richardson considers the rise of the political Outsider, and what it means for South Australia.

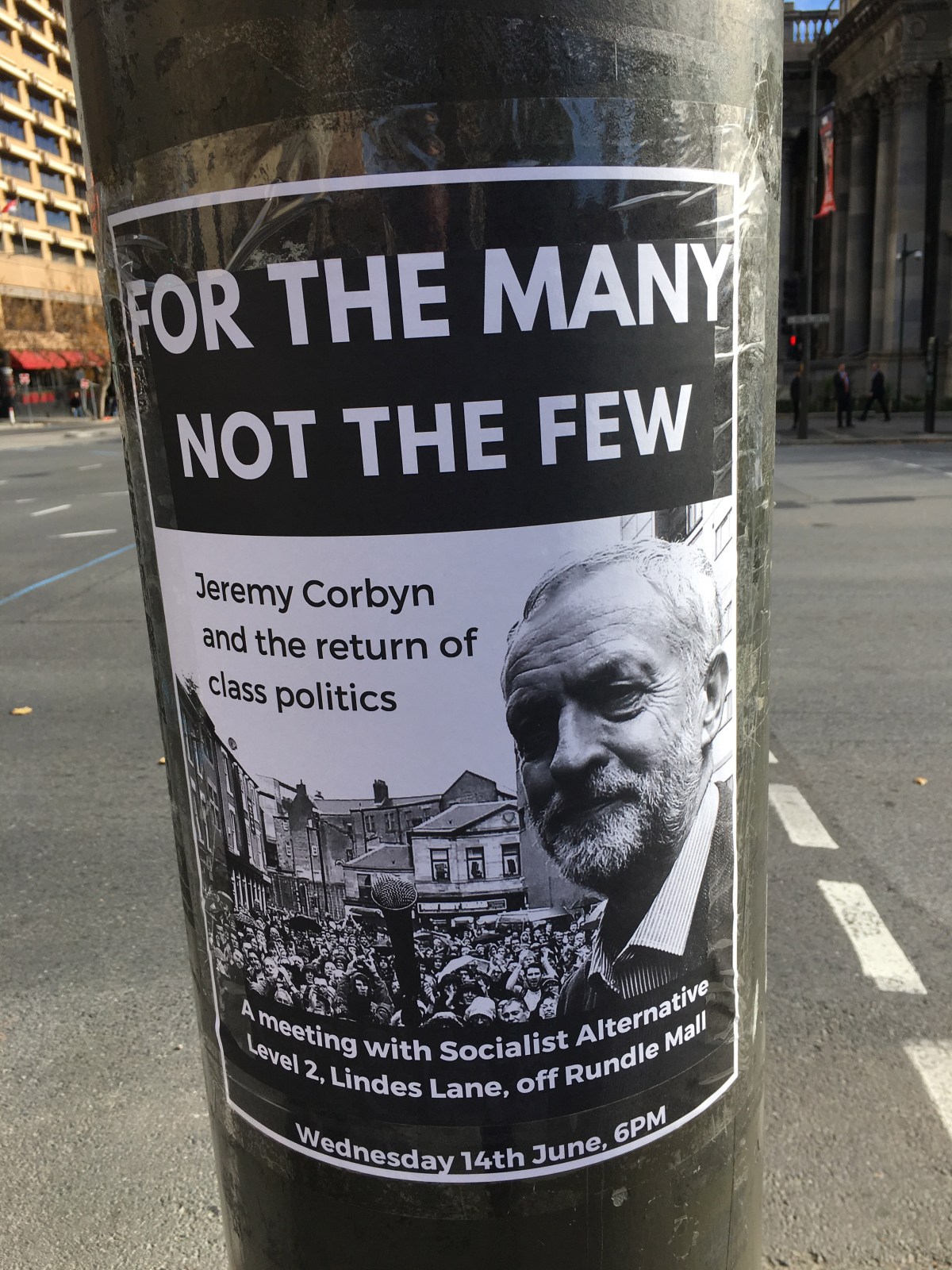

Left or right? Jeremy Corbyn's success in Britain could be less about ideology than challenging the status quo. Photo: Stefan Rousseau / PA Wire

In the breathless fallout of Jeremy Corbyn’s election victory (wasn’t it?) in the UK last week, Labour’s resurgence – and the decline of the minor party vote – has been attributed by some as a return to the two-party hegemony.

It’s not. In fact, the general election result was more akin to a revolution than a return to politics-as-usual.

Making my way from a parliament house press conference this week, I spied this flyer (above) for a Socialist Alternative event (before you rush to book early to avoid disappoint, I’m sorry to tell you that you already missed it).

What does this tell us?

Well, firstly, that the socialist left is (quite understandably) celebrating the groundswell of popular support for one of its own (albeit that the socialist left has always fundamentally prided itself as a grassroots and defiantly non-mainstream movement).

But an analysis of what happened in Britain that celebrates the return of class politics is inevitably short-sighted.

Sure, Corbyn’s politics have evolved (and not very far) from the old Bennite Left, whose influence on Labour was at its zenith when, in 1983 under the doomed leadership of Michael Foot, it published an election manifesto dubbed by one of its own frontbenchers as “the longest suicide note in history”.

Among other things, the 39-page document advocated tax hikes for those on higher incomes, re-nationalisation of privatised industries, unilateral nuclear disarmament, and withdrawal from the European Economic Community.

The manifesto Labour took to last week’s general election, some 34 years later, advocated tax hikes for those on higher incomes, re-nationalisation of privatised industries and an acceptance of the referendum result to leave Europe. It did commit to keeping a nuclear deterrent, although the extent of that commitment became less clear as the campaign wore on.

So, after 34 years have all the workings of the so-called Loony Left suddenly gained mainstream acceptance?

Have Labour’s downtrodden working classes risen up to (almost) achieve the socialist dream of a genuinely left-wing Labour Government?

I doubt it.

But more to the point, Corbyn’s success should not be viewed through the prism of left and right, although it undoubtedly will be.

Corbyn’s feat has largely silenced most of the Labour moderates who shunned him, walked out on his cabinet and pronounced him unelectable.

Perhaps he should be thanking them. It’s arguable that they helped make him electable, by reinforcing his status as a political outsider, shunned by the party establishment.

And Corbyn is, after all, a career outsider.

But if you maintain the same ideological bent for a very long time, you will eventually find the political poles shifting around you.

Shortly after that 1983 manifesto helped Labour to a cataclysmic defeat to Thatcher’s Tories, one of the more intense, bitter and symbolic industrial battles in union history played itself out, with the Left defending its coal-mining heartland against Government closures of pits deemed uneconomic.

These days, of course, the political Left demonises coal as a pollution-spewing industrial relic holding back the onset of environmentally-friendly energy generation, and agitates for its swift demise.

The ambassadors of the political Right, on the other hand, affectionately pass round lumps of the stuff in parliament.

Swings and roundabouts.

So, is defending coal a Left issue… or a Right one?

Photo: Mick Tsikas / AAP

But in many ways, the issues shaping the election haven’t changed.

Europe has dogged the far left and right of both Labour and the Tories for generations, and has prompted more than one change of leader in the meantime.

So it’s not an issue of Left or Right, but of a nation’s place in the world.

And it would horrify those celebrating socialists to think it, but Corbyn’s unexpected success fits more neatly – albeit bizarrely – in the political tradition of Brexit and Trump. It is not an endorsement of left-wing politics, but of Outsider politics.

True, his politics couldn’t be further from that of the US President, but they have this much in common: much of their appeal was derived by a deep and abiding dissatisfaction with mainstream politics, and a belief that they were somehow beyond the political establishment.

Corbyn has been a life-long maverick, a backbench agitator who only months before he was catapulted into the Labour leadership by a disaffected membership had written a glowing defence of the party’s 1983 manifesto, noting it would be “highly appropriate today to deal with the finance and banking crisis that has been visited upon the poorest people in Britain”.

Class politics in the UK is more acute than it is in Australia, because the divide is greater. The politics of privilege has been invoked again in the election’s aftermath, with the hideous tragedy that unfolded in the Grenfell Tower housing estate.

Eerily and depressingly, this same scenario – almost exactly – was once fictionalised in Michael Dobbs’ To Play The King, the sequel to the original British novel-cum-serial of House Of Cards, which has now been bastardised by an inferior US remake, as is the way of things these days.

In Dobbs’ narrative, a gas explosion in a block of flats heightened a debate about lacklustre investment in housing and social services.

If nothing else, it suggests it is a debate that has been left unresolved for the subsequent quarter century.

Grenfell Tower is in a pocket of social housing in the generally upmarket seat of Kensington, which is better associated with expensive apartments and a high-end retail hub. The seat was won by Labour’s Emma Dent Coad last week; it’s the first time the party has ever held the seat.

Kensington is a weird symbol of the general election, in which areas peopled by well-to-do professionals came out in droves for a Labour leader determined to raise their taxes, while seats filled with anxious workers in declining industries voted for the party of austerity.

This doesn’t suggest a re-emergence of class politics as much as a redefining of it.

Jeremy Corbyn leaves Labour headquarters after the election. Photo: EPA

And the key could well be not that we are still engaged in the same debates we were 30 years ago, but that the electorate is weary of the fact that nothing ever seems to be resolved.

Much has changed in Britain in that time, from a highly fractured political divide to a new fiscal consensus; Labour’s return to the politics of nationalisation was a curveball, but it reflected the fact that the electorate is still not convinced that the politics of consensus has worked.

It has taken a long time for the notion to permeate that politics as usual has left us going round in circles on the same issues for a generation.

And that can help to explain recent high-profile instances where electorates have opted for something other than politics as usual.

Hillary Clinton was, as Obama put it, the most qualified person ever to run for the Oval Office. She didn’t fail despite this fact, but because of it.

Corbyn, who was expected to be trounced in a defeat worse than that 1983 bloodbath, instead increased Labour’s vote, despite the kind of vociferous media bile that used to be reserved for the likes of Tony Benn and Neil Kinnock.

THE SUN FRONT PAGE 'Don't chuck Britain in the Cor-bin' #skypapers pic.twitter.com/bzJOOvu1lT

— Sky News (@SkyNews) June 7, 2017

What does that tell us? If we needed further evidence after Trump, it suggests the power of mainstream media is greatly diminished in modern politics.

And why? Because mainstream media is now seen as part of the establishment, the power elite.

The Fleet Street mastheads are part of the insider politics hegemony. This result was as much a rebuke of them as it was of Theresa May.

In Australia, there is much evidence that the rise of Outsider politics will continue to wreak havoc on the two-party duopoly.

The re-emergence of Hanson and the enduring popularity of Xenophon are two such examples, along with the re-election of Jacqui Lambie. I suspect Cory Bernardi’s Australian Conservatives will similarly find fallow ground to plant deep electoral roots; indeed, I am increasingly confident the fledgling party will be a significant factor in next year’s state election.

Because there is an electorate out there clearly underwhelmed with the mainstream.

Some Labor insiders evidently believe Jay Weatherill’s appeal is somehow akin to that of Trump or Corbyn – a maverick outsider who, by berating federal politicians and throwing up big ideas, can engineer some kind of popular uprising by disaffected South Australians.

If that was ever true, his lack of results has dimmed that notion. But for the party that has governed for the past 16 years to somehow claim Outsider status is in any case ludicrous.

But if voters appear disillusioned by Labor, they remain consistently underwhelmed by the Liberal alternative.

The nature of the political challenge for SA is succinctly spelled out in this missive on the looming election:

“SA remains a troubled state with a fragile economy, heavily reliant on manufacturing and mining… many of the new jobs created are casual and part-time.

“Jobs, health care, crime and education dominate the agenda in the lead-up to the state poll but a major problem for the state’s economy remains the price and reliability of electricity.

“The national grid was supposed to increase competition and drive down prices, but SA has failed to adequately tap the rich supplies of other states and continues to rely on its own, more expensive power. Business leaders have warned that continued electricity price hikes will only provide more incentive for them to look beyond SA, making the resolution of the power crisis a priority for the next government.”

A handy explainer, with one problem.

It’s an excerpt from a piece written by Carol Altmann for the Australian newspaper’s Political Almanac – published in 2002!

There is a palpable sense that the political establishment has failed to solve – or even tackle – the problems facing SA, and reading this snapshot retrospectively, it is hard to escape the sense that on a range of fronts the last 16 years have been less a squandered opportunity than a complete waste of time.

When politics as usual fails, it creates the vacuum for a Trump or a Corbyn or a Xenophon… someone who can promise a new style of politics.

The March election could well herald the rise of one such Outsider. It’s just a question of which one.

Tom Richardson is a senior reporter at InDaily.