Personal attacks on judges undermine our democracy

Attacks on the judiciary by President Donald Trump typify commonly-held misconceptions about the role of judges in the legal process and their importance to democracy, writes InDaily’s legal commentator Morry Bailes.

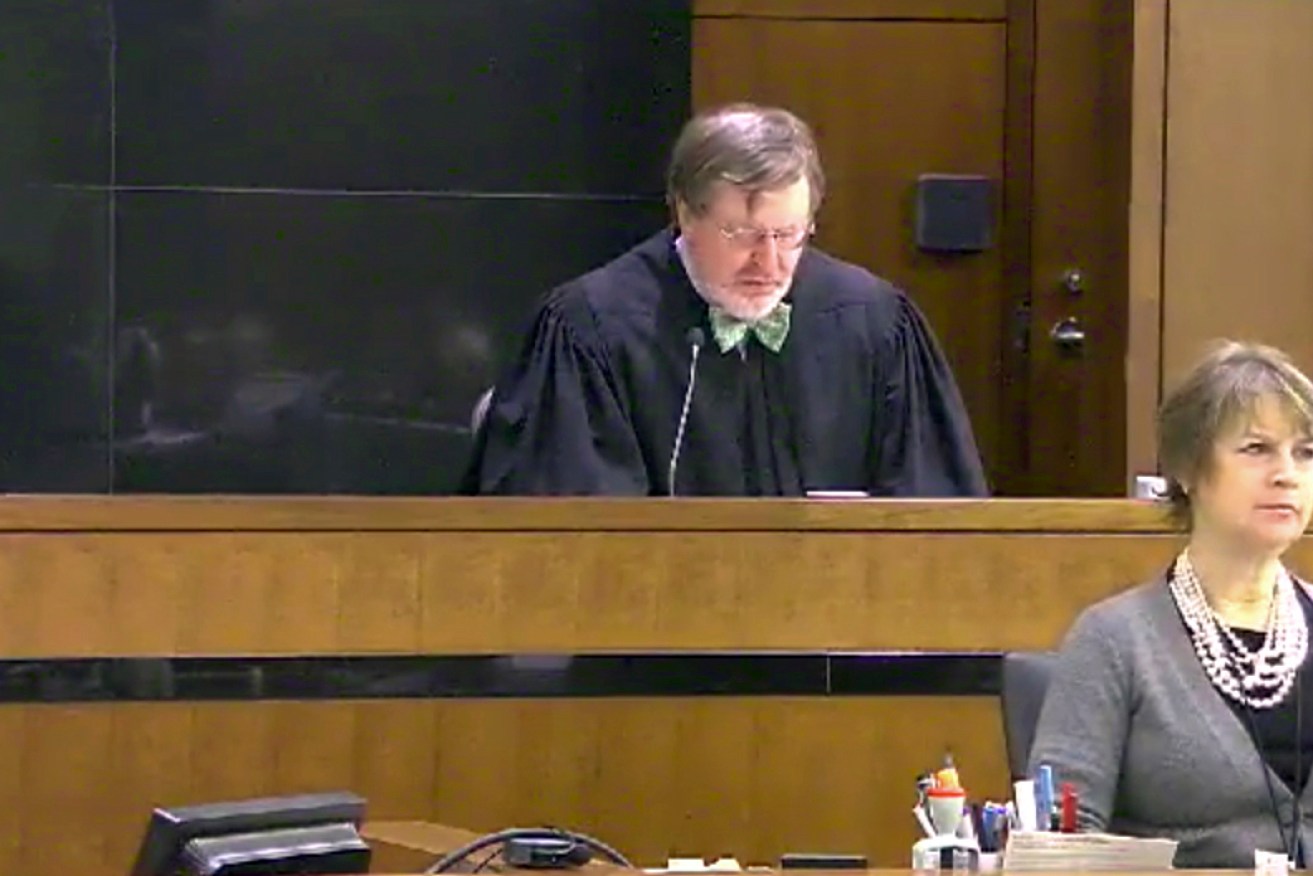

Judge James Robart has been subject to a personal attack from US President Donald Trump. Photo: United States Courts via AP

After a week in which the new Trump administration put the world on notice, it was President Trump’s derisive reference to a “so-called judge” that really raised my ire. He was referring to the federal district court judge who ruled against the US Government’s “travel ban”.

What the judge decided was the lawfulness of a presidential executive order in the context of federal versus states’ rights, and in the cases of the individual matters before him (although his decision now applies to the whole of the federation). The effect of the decision was, in fact, to grant a temporary restraining order.

The President went on to describe the judgement as an “opinion” when, of course, it was a judgement – there is a difference. He obviously didn’t like it, but courts aren’t popularity contests and are not constituted to be liked. They exist to rule on law.

In a democracy, the judiciary is entirely independent and separate to executive government. It has to be that way because the judiciary is the final check against decisions by law-makers, in this case by executive order, that may be found to be unlawful, irrespective of whether the judge personally liked or disliked the Presidential decree. What he found, quite simply, is that it was likely beyond power, which warranted the granting of the temporary restraining order.

To illustrate the point, in the famous Tasmanian dam case in the early 1980s, the decision was not about whether the court wanted to protect the environment, it was about the external affairs power in the Australian Constitution, and whether the Commonwealth of Australia could roll the State of Tasmania on a states’ rights point. The case is not taught in law schools because we agree or disagree with damming the Franklin River. It is taught because it established what the Commonwealth and states could and couldn’t do under the Australian Constitution. And when Tasmania lost, the Premier of the day didn’t accuse the judges ruling in the matter as being “so-called judges”. His government wore the result. That’s how we maintain our democratic systems of government. Laws have to be lawful.

I do not know whether Judge James L. Robart’s judgement will be upheld or overturned on appeal nor where this case may then go (to the US Supreme Court in all likelihood). Many a matter from a Magistrates Court in this country has ended up before our High Court. What is interesting is Robart’s express reference to the doctrine of the separation of powers. At the conclusion of his judgement he said: “Fundamental to the workings of this court is a vigilant recognition that it is but one of three equal branches of our federal government. The work of the court is not to create policy or to judge the wisdom of any particular policy promoted by the other two branches. That is the work of the legislative and executive branches and of the citizens of this country who ultimately exercise democratic control over those branches. The work of the judiciary, and this court, is limited to ensuring the actions taken by the other branches comport with our countries laws, and more importantly, our Constitution.”

If you, as a party in litigation, disagree with a judgement, you appeal it. But you ought not to imply that a judge is not a judge and that a judgement is not a judgement. Even when our politicians often improperly call into question a judgement, it is ordinarily aimed at the judgement or the parliamentary law leading to the decision, not questioning the validity of the judge or reducing the standing of the judgement to that of an “opinion”. Opinions are what barristers and lawyers give. Judges deliver binding judgements, unless successfully appealed.

I understand there is a war of ideas in the US at the moment. I have heard friends, acquaintances and colleagues from both sides of the fence join the chorus of debate, each one convinced of the originality of their view. No matter how frenzied the debate comes, we must not forget or tread upon the basic tenets of government, which includes the separation of powers and the independence of the judiciary. The criticise a judge is to criticise the office of the judge. To criticise the office is to undermine public confidence in the decisions of the judiciary and gradually erode its independence.

Ironically, the Trump nominee for the US Supreme Court, Neil Gorsuch, made precisely that point when fronting the media (the appointment of Supreme Court judges in the US being a great deal more political that the appointment of High Court judges in Australia). He said he stood as an independent judicial interpreter of statutory law whether he agreed with the statute or not. To quote his words: “A judge who likes every outcome he reaches is very likely a bad judge stretching for results he prefers rather than those the law demands.”

In a further irony, Gorsuch’s approach happens to be a conservative or textualist approach to judicial interpretation. No implied rights there. What does the ink and paper say? Is the ink on the paper constitutionally lawful or unlawful? “What the words on the paper say,” is the Gorsuch motto. Therefore, there is no point criticising those applying it. The only correct avenue for dissent is an appeal; any accompanying commentary is for political purposes, the casualty of which is the reputation and thereby the independence of the judiciary.

Not everything that governments do is constitutionally lawful. Why are we troubled about testing the validity of our law? Why are we concerned that we have the privilege of an independent judiciary?

Think of the vilification handed out by the Fleet Street press when three High Court judges in the United Kingdom found that the Brexit referendum had to pass through the Parliament. However, in that case it was the press trying to sell newspapers who acted improperly, not the British prime minister. The decision was appealed, the judges were upheld and the laws then passed through the British parliament. So much for all the criticism.

My opinion has scant to do with politics. It has to do with our democracy and how not to trash it. I have no idea how this legal saga in the US will play out, but that is not the point. What we are witnessing is the deliberate political questioning of a court’s ruling, be it right or wrong, when the only mechanism that matters is the appeals process. Countries are entitled to take action to protect their borders but courts in the US and Australia have been asked to evaluate the lawfulness of orders – and so they should. How else do we set a course that maintains good law? Not everything that governments do is constitutionally lawful. Why are we troubled about testing the validity of our law? Why are we concerned that we have the privilege of an independent judiciary?

As a legal traditionalist I remain concerned by politicians who call into question the decisions of an independent judiciary, particularly when they are heads of state. To preserve what we have as free western democracies, we all are subject to the law and all are treated equally in its eyes, including the President when he exercises executive power. Politicians are not entitled to improperly question an independent judiciary, just as the judiciary ought never question parliament but stick to the job of statutory interpretation.

I don’t want to wrap cotton wool around the judiciary. Criticism might influence public perceptions, but it also causes people like me to pick up the pen to clarify our democratic architecture, and encourages judges to fortify their view about their independence and impartiality.

Another American President, their seventh, Andrew Jackson, said: “All the rights secured to the citizens under the Constitution are worth nothing, and a mere bubble, except guaranteed to them by an independent and virtuous judiciary.”

The independence of judges is not helped by politicians undermining public confidence in their office. It is reprehensible when it becomes personal.

Our politicians may be elected by the will of the people but, like judges, they come and go. The office of parliamentarian, judge or President, however, remains, and it is these offices that we must never tarnish.

Morry Bailes is the managing partner at Tindall Gask Bentley Lawyers, president-elect of the Law Council of Australia and is a past president of the Law Society of SA. The opinions expressed in this column are his own.