Richardson: Left, right, left – the confused march of the neverending election campaign

Arguments about protecting Australian jobs have ignited an otherwise dreary election campaign. But, as Tom Richardson writes, the rhetoric exposes inherent ideological contradictions within both major parties.

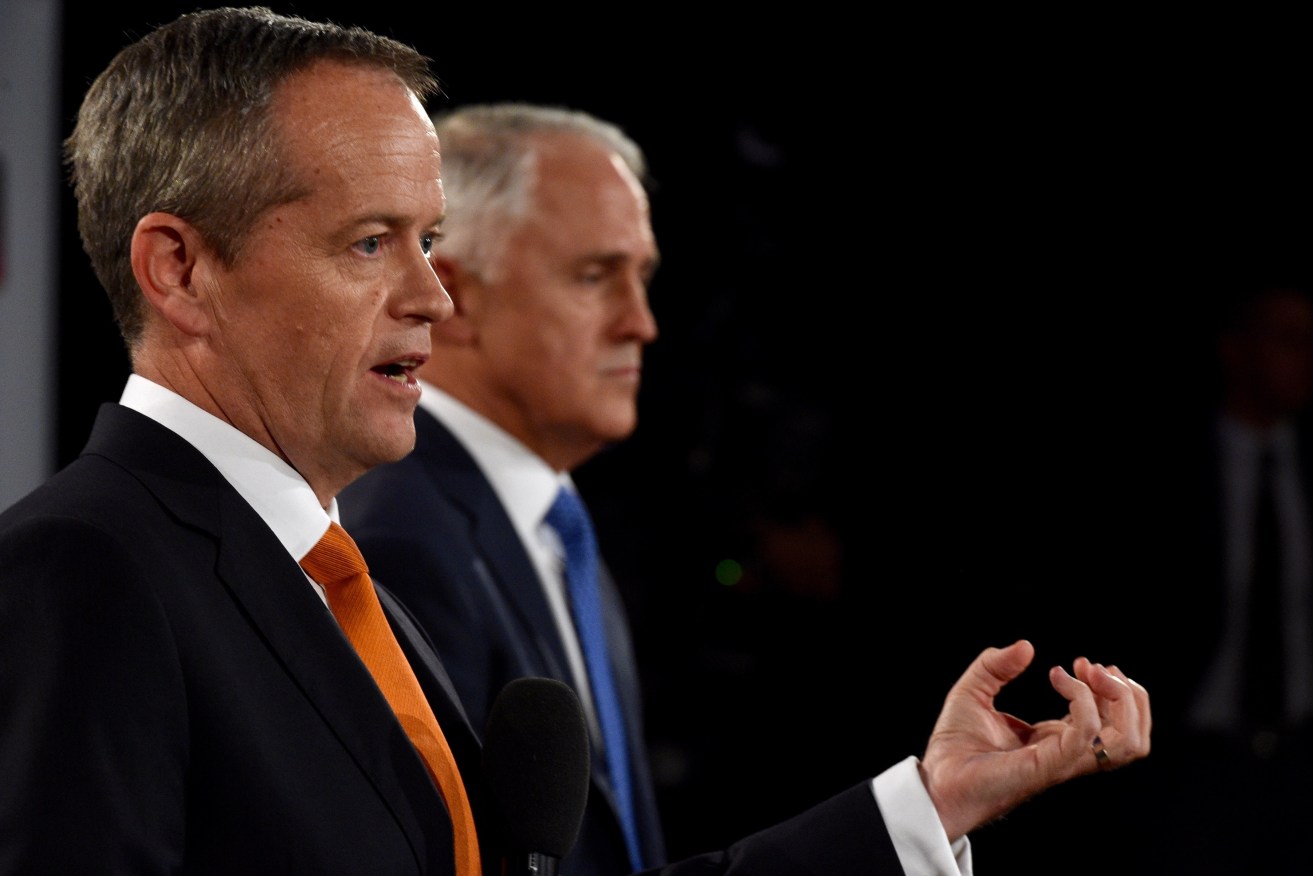

Shorten and Turnbull are both running presidential-style campaigns, but to whom are their respective parties appealing? Photo: Mick Tsikas, AAP.

Are we having fun yet? The Neverending Story that is the 2016 election campaign is rolling towards the end of its third week, which means there is only the full calendar month of June – plus a bit more – to go.

And what a frenetic and heartstopping campaign it has been, with a transfixed nation hanging on every golden word that has emerged from the lips of our esteemed leaders.

Or not.

Actually, the best thing about the campaign thus far is the recommencement of hostilities between Hollywood has-been Johnny Depp and his self-styled Hannibal Lecter nemesis Barnaby Joyce.

There are (at least) three compelling reasons why an eight-week election campaign was a lousy idea in terms of engaging the electorate.

Firstly, voters are already perhaps more cynical and weary than ever before of those who govern and purport to govern, and subjecting them to a protracted series of one-liners and selfies is hardly going to disabuse them of their distrust.

Second, in purely political terms there is less chance to simply deliver a cogent message in this meandering mess. Many voters are unlikely to engage with the campaign until its dying days, but the risk is that by then they’ll be so thoroughly sick of Messrs Turnbull and Shorten and their assorted hangers-on that they’ll actually end up less informed, not more.

Finally though, and this is a dichotomy long in the making but rarely given due consideration, the nature of the respective parties’ political ideologies has become so muddied and confused, it’s little wonder they both struggle to explain exactly what they stand for.

The issue for both Liberal and Labor lies in their respective inabilities to marry their social and economic agenda – and moreover to present both in a way that will appeal to a significant constituency.

Probably the talking point of the campaign thus far was Peter Dutton’s ham-fisted attempt to up the ante on immigration last week, when he claimed that illiterate and innumerate refugees would both take Australian jobs and “languish in unemployment queues and on Medicare and the rest of it”.

“There’s no sense in sugar-coating that, that’s the scenario,” he added helpfully.

His efforts were neatly derided as a dog-whistle by furious critics, but his rhetoric deserves some consideration in the broader context of conservative ideology.

The Liberals are, after all, ostensibly free marketeers for whom the retention of economic borders is anathema to good governance.

What was interesting about Dutton was how he reframed the immigration debate down to its basest level – “they will take our jobs”.

Which is, presumably, the highest hope for any immigration policy – that its beneficiaries integrate and find meaningful work.

Under Howard, immigration as an election issue was more often framed as an issue of sovereignty: “We will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come.”

Latter era asylum seeker policy has been more often framed, at least by the more thoughtful conservative commentators, as a bid to avoid mass deaths at sea.

While he was talking specifically about increasing Australia’s humanitarian refugee intake, Dutton’s monologue rejected all that. His rhetoric eschewed humanitarian ideals, appealing instead to narrow parochialism.

But where was this narrow parochialism and this determination to safeguard presumably low-skilled Australian jobs when the Coalition pulled its support – both financial and political – for the domestic auto industry?

When Toyota pulled the pin on its Victorian operations in February 2014 – the culmination of a domino effect following Holden and Ford’s decisions to exit – it said in a statement that there was no “single factor” that led to its demise.

“The market and economic factors contributing to the decision include the unfavourable Australian dollar that makes exports unviable, high costs of manufacturing and low economies of scale for our vehicle production and local supplier base,” the statement said.

“Together with one of the most open and fragmented automotive markets in the world and increased competitiveness due to current and future free trade agreements, it is not viable to continue building cars in Australia.”

In other words, Australian jobs were lost due to Government policy that would instead see work exported.

And yet no-one from the Government was spouting the “they took our jobs” rhetoric over free trade.

Of course not.

But the commitment to opening up economic borders while clamping down on geographic ones has an inherent inconsistency.

Just, indeed, as does the political Left’s more humanitarian stance on immigration policy – at least rhetorically – while still maintaining a deep-seated predilection to a fortress economy.

Labor’s instinctive response to the mass auto industry exodus was that we did not spend enough to keep it here.

Its subsequent response is that we should spend more to provide jobs for those displaced.

Shorten’s tortured objections to the China Free Trade Agreement were couched in the spectre of foreign construction workers being brought in on major projects worth more than $150 million.

Or, to shorten Shorten, “they’ll take our jobs”.

The great irony of our political landscape since the mid-90s advent of Pauline Hanson has been that the old Left has more in common with the new Right than it does with the ALP.

Ironically, the most cogent critic of the recent spate of FTAs was the Productivity Commission, generally lambasted as the poster child of laissez faire economics, whose 2014 review would have killed off Holden in any case if the company hadn’t already wielded the knife itself.

In a review last year, the commission noted that “preferential trade agreements add to the complexity and cost of international trade through substantially different sets of rules of origin, varying coverage of services and potentially costly intellectual property protections and investor-state dispute settlement provisions”.

It argued that multilateral – rather than bilateral – trade “is the most effective way to improve national and global welfare”.

In SA, Jay Weatherill has had the luxury of advocating for greater humanitarian immigration, even offering to bear the cost of resettling displaced Syrian refugees on temporary safe haven visas last year.

But his own policy projections suggest a different story: in a recent speech to the Urban Development Institute on Labor’s review of its 30-Year Plan for Greater Adelaide, he revealed the state’s population was expected to grow by 545,000 over a generation – 15,000 less than the population growth predicted under former Premier Mike Rann’s state Strategic Plan.

That means there is no genuine commitment to bringing in more migrants, despite the lip service.

Presumably because they’ll take our jobs.

It’s just that a Labor Government won’t say so explicitly.

That Dutton’s idiocy was derided by the Left was to be expected; the question is to whom he intended to appeal. Probably less to free market small-l liberals than to displaced blue collar workers feeling insecure about their future prospects. People who, on paper, would consider themselves traditional Labor voters.

The great irony of our political landscape since the mid-90s advent of Pauline Hanson has been that the old Left has more in common with the new Right than it does with the ALP. Its mission is to use the levers of Government to protect domestic jobs, and as such the protectionist rhetoric of border control is designed to resonate with its disenfranchised disciples.

Perhaps the reason both parties have trouble connecting with the electorate is that they can’t work out which part of the electorate they represent anymore. There’s another great irony in the fact this double-dissolution election was predicated on a bid to curtail the union movement. Because if Dutton’s rhetoric last week was indeed a dog whistle, it was one directed at that movement’s most marginalised members.

Tom Richardson is a senior reporter at InDaily.