London bombings 10 years on: what we’ve learnt

The number 30 double-decker bus in Tavistock Square, which was destroyed by a bomb in the terrorist attacks of 7 July, 2005.

A decade after the London bombings, we know a lot more about why people become radicalised, writes Matthew Francis.

As the UK marks the tenth anniversary of the July 7 London bombings, there is a sense that what was a terrible new phenomenon in 2005 has become increasingly prevalent.

Back then, the country was shocked when 52 people died at the hands of four British nationals who had brought what they saw as a religious war on to the streets of London – and were willing to die in the process. In the 10 years since, more have taken a similar path, causing anxiety about how long it will be before another attack happens and how these people are to be stopped.

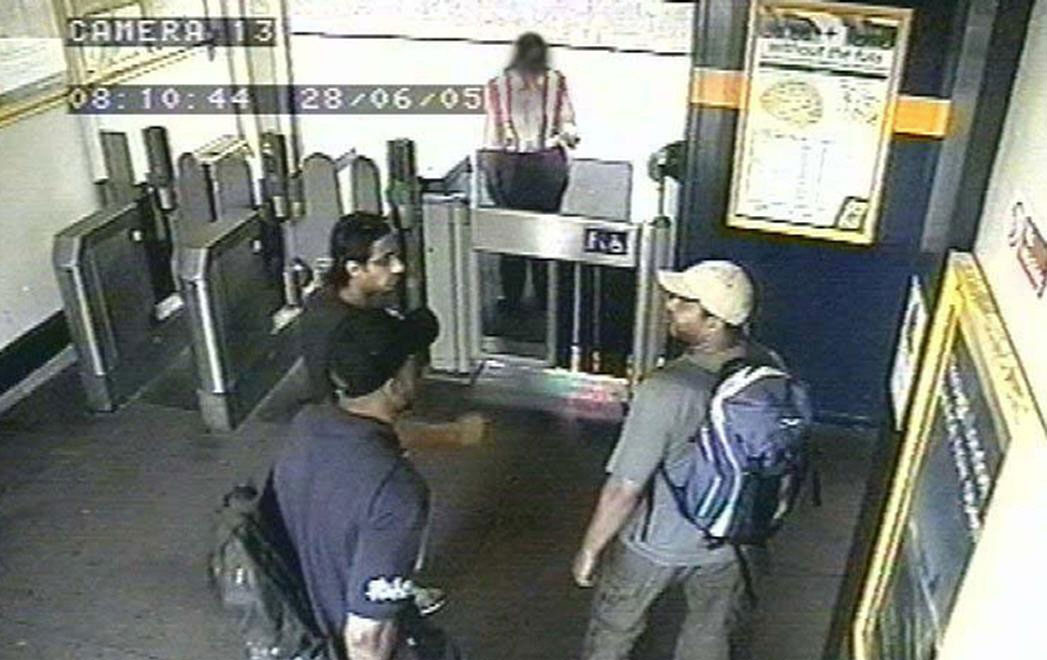

The flight of men and women to join Islamic State might lead us to believe, depressingly, that we haven’t learned anything since 7/7 – when the four young men entered the London transport network carrying their backpacks of explosives. But the truth is very different. We’ve learnt, and are learning, a tremendous amount about how and why people choose to get involved in terrorism.

We’ve picked up plenty of useful information about what leads people to join radical groups and how their path is made easier – or indeed harder. Now it’s a matter of applying that knowledge effectively.

Not all about religion

One of the most important lessons has been that, while it is important, radicalisation is not all about religion. Since 7/7 the media and the government have struggled to understand what role religion played in the London attacks and others around the world. Often the explanations are restricted to simplistic reductions of Islam. The perpetrators are either following a religion of war, or a perversion of a religion of peace.

These accounts fail to understand that religion, even Islam, is not practised in the same way by all Muslims and that there isn’t a commonly agreed “right” way of being a Muslim – despite proclamations to the contrary from Islamic State.

That said, we shouldn’t stop trying to understand the role ideology plays just because it is complicated. We know, for example, that people and groups choose more extreme beliefs at times of uncertainty. We also know that while ideology plays a role in radicalisation, engagement with a terrorist group or action requires other enabling factors – such as access to weapons and acquiring the ability to use them.

The quality of public conversation about religion is often poor but the situation is improving. There has recently been a greater effort to increase religious literacy in general and to improve the place of education about beliefs in schools, for example.

We won’t stop terrorism with these kind of efforts, but improving general understanding about religion and ensuring that people are able to talk about it will help young people challenge toxic and dangerous ideologies better than they can at present.

What cults tell us

As we’ve tried to come to terms with a new threat over the past decade, the work of groups specialising in minority religious and political movements has proved useful.

Research has shown that while the vast majority of minority religions aren’t violent, there are still lots of similarities between the process of joining a terrorist group and joining high-cost groups that exist on the fringes of society – violent examples of which include Aum Shinrikyo and the Solar Temple.

Such groups provide a place for disenchanted people to call home. They do this through constant positive messaging – or “lovebombing” – to convince the person that they have found a purpose in life. Once in these groups, people often act in ways that they never previously would have considered, even cutting off all ties with family and friends.

But being a member of high-cost groups can also be very demanding – and this can be one of the reasons people choose to leave. In extreme cases, people can be faced with violence if they try to leave and can be further deterred by the fact they lack job prospects and social networks on the outside.

The importance of providing personalised support to people who want to leave these groups has been echoed in policy, for example the UK’s Channel programme. This is an important lesson, confirming that while we look to understand patterns in why people join – and leave – these kinds of groups, the actual reasons are unique to each person.

Social networks are vital

Attention has recently turned to the role of social networks in leading people into radicalisation. It seems that prior personal ties can ease uncertainty about taking part in action, for example. Research on the far-right group the English Defence League shows that people attending their first protest found it easier if they already knew other people going as a result of previous participation in far-right activities or football hooliganism.

One particularly important finding has been that decisions to act, violently or otherwise, are taken collectively and there is evidence of block recruitment to activist movements.

We’ve seen this in recent cases of people joining IS, with groups of friends from Cardiff, East London and Portsmouth leaving for Syria together. This is important because we’ve seen that these people don’t act out of ideological commitment alone, but often because of personal ties.

Even more importantly, we know from the study of social networks and cults that when people are in tight-knit groups there is a confirmation bias in the way they view the world. Their perceptions are reinforced by like-minded individuals.

Conversely, people with stronger ties to wider society are less susceptible to joining high-cost groups or being convinced by their way of seeing the world. The UK’s Prevent strategy did originally try to encourage social cohesion through inter-communal activity, although that aspect of its mission has been poorly resourced.

Shehzad Tanweer (left to right) Germaine Lindsay and Mohammed Sidique Khan in Luton Train Station, June 28 in an apparent dry run of their devastating attack. Source: Metropolitan Police

Dealing with foreign fighters

While the number of people leaving to fight abroad is a sensitive issue at the moment, it certainly isn’t a new phenomenon. We could do worse than to look at history for some clues about how to tackle this issue.

Around 100,000 people have taken up such endeavours over the past 250 years. Most go home, even back to their old jobs, when they leave. There are still problems with counting how many have been involved with violence back at home but research suggests the figure is less than 10%.

A further concern has been that returnees could be used for recruitment and facilitating travel, but because of social media they no longer need to recruit in person. Indeed, we could even say that with their tall tales of derring-do on the battlefield, they are more effective when they stay abroad to fight.

One of the interesting lessons we’ve learned from historical analyses is what happens when citizenship is stripped from foreign fighters. Many people from various Middle Eastern states had their citizenship revoked when they left to fight the invading Soviets in Afghanistan. This not only prevented them from returning home, it bound them together as they looked for a way to use their new skills – and, with financial aid from Osama bin Laden, some of them formed the core of al-Qaeda.

The blanket policy of stopping foreign fighters from returning is misguided, since many may head home because they no longer believe in the radical ideology of IS – if indeed they ever did. Still, as research on former cult members has shown, the reasons people give for disengaging with groups change over time. While they might initially claim they had realised they’d been brainwashed or duped, it often turns out they had simply fallen out with other members.

Stop calling them lone wolves

One step that could be taken to prevent people from joining these groups is to think more carefully how the media glamourises them. A good case in point is the moniker “lone wolf”, which implies a sense of cunning and intelligence that violent lone actor terrorists often sorely lack in reality.

Think of Mohammed Taheri-azar, who first planned to hijack a fighter jet and drop a nuclear bomb on Washington DC; his plan B was a campus shooting spree, but he was ultimately unable to carry out either attack. In the end he ran over and injured nine people.

A crucial turning point for Islamist-inspired lone actor attacks was the murder of Lee Rigby. With the sheer impact of their actions, Michael Adebolajo and Michael Adebowale showed aspiring lone actors that even with little ability and minimal resources, it was still possible to vault into the social status and notoriety that so many desperately crave.

But this desire for infamy is one of the reasons lone actors leak details of their attacks before carrying them out. Research has shown that leakage of plans is quite common. Understanding how and why these leaks occur is another example of significant outcomes of research since 7/7. Detection is still harder for police and other agencies than prevention, but detecting and stopping lone actors requires more attention than disrupting the communications of IS.

Shifting tactics

Since 7/7 we have learned a tremendous amount about radicalisation. But what about the future? During this time, research has adapted to focus on new technologies and shifting tactics, such as cyber-activists and the proliferation of lone actor terrorists.

This research is shared with decision-makers in government and is used to critique policies and strategies.

While the threat from terrorism will undoubtedly remain and continue to innovate, it is clear we understand it better than we did back in 2005.

Matthew Francis is a senior research associate in the Department of Politics, Philosophy and Religion at Lancaster University.

This article was first published at The Conversation.