Flowers from France: Sleuthing a Remembrance Day letter

In 1916, a soldier in France wrote a brief letter to an Adelaide woman, whose family business is still prominent today. To mark this day of remembering, Simon Royal enlists expert help to unlock some of the mysteries contained within the poignant correspondence.

A photograph of Vera in front of some of the letters she received from soldiers. Photo courtesy the ABC

Somewhere in France, in the middle of the northern summer, a soldier stopped to pick a sprig of flowers. They were only tiny things, but what they lacked in size they more than made up for with a striking shade of blue – they were spectacular.

Perhaps the flowers jogged the soldier’s memory of easier times, the colour reminding the young man of the intense azure of an Adelaide summer sky. He hadn’t seen one of those since he and the rest of the 32nd battalion sailed out of Port Adelaide – off to join the Great War then raging in Europe.

Carefully, the soldier pressed the flowers. He wanted them to stay beautiful. Then, grabbing a sheet of tissue thin paper, the soldier wrote a letter back home in the elegant cursive characteristic of his generation.

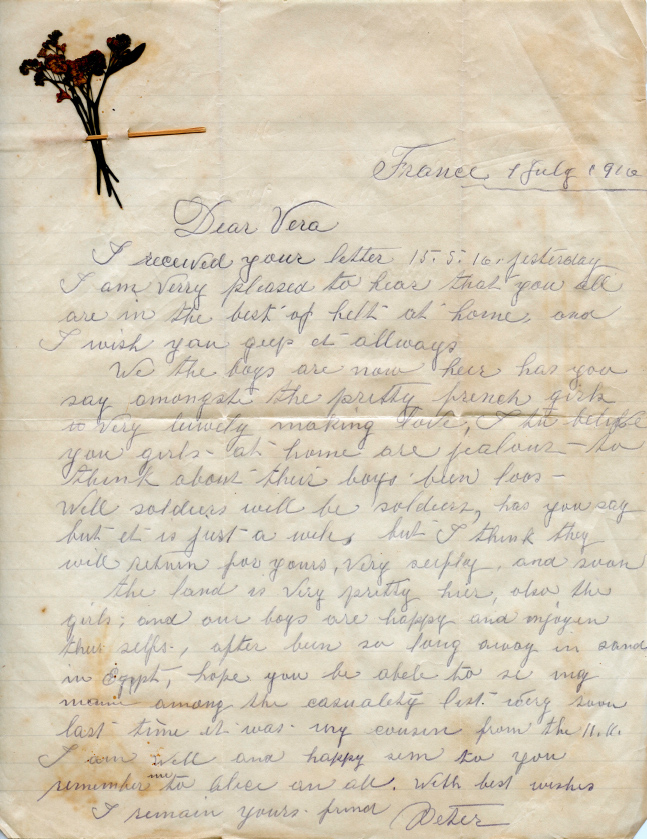

He pinned the flowers to the letter’s right-hand corner and addressed it to a friend: Miss V.L. Rossiter, 225 Young Street, North Unley, Adelaide.

The soldier knew Miss Rossiter – Vera – would appreciate his gesture. The pair were familiar enough that the soldier signed the letter using only his first name – “I remain yours [sic] friend Peter.” In the top left-hand corner, the soldier put the date: July 1, 1916.

A century later the letter is faded but intact. So, too, are the little blue flowers – still right where Peter put them. The details are scant but they’re enough for a botanist, an historian, and Vera Rossiter’s grandson, to tell the story of the day the soldier wrote his letter back home.

Peter’s letter to Vera, with flowers pinned to the top left.

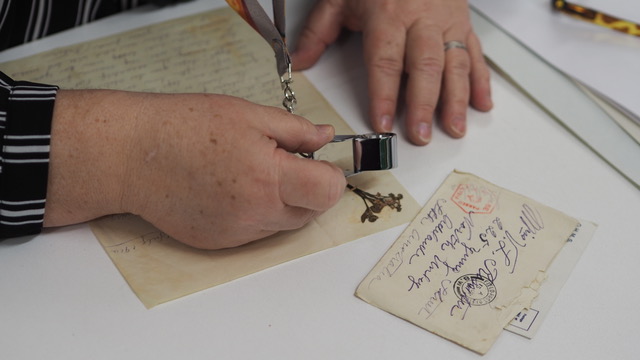

Professor Michelle Waycott is Chief Botanist at the State Herbarium, with over 30 years’ experience unlocking the secret lives of plants. The most common professional hazard/joy the professor faces is the usual question: “And what type of plant is this”? For some species, such as eucalypts, the answer is straightforward – the smell is a giveaway. Other species, though, are more guarded.

Michelle Waycott, the State Herbarium’s chief botanist. Photo: Simon Royal

“There are probably over 300,000 species of flowering plants, so there’s a lot choose from,” Professor Waycott says. “You narrow it down by a process of elimination. It’s like being a detective, or a sleuth!”

The investigation begins, and sometimes ends, with the quality of the specimen and how well it’s been preserved. As Waycott dons an eyeglass and leans over the soldier’s letter for a closer look, (she pronounces it, “quite a nice specimen”), she explains the pros and cons of various preservation methods.

“A really good field botanist will try to press things so that you can maintain three-dimensional shapes,” she says. “The relationship of the various parts of the plant is an important part of identifying a specimen.”

Colour, the quality that first catches our eye with flowers, can’t necessarily be relied upon. That’s because some species change colour as they dry out. The inherent fragility of dry things doesn’t help, either.

“That’s why sometimes we pickle things rather than press them,” Waycott says, before announcing with a great laugh: “You know a really good quality gin can be used for many, many things. There’s the odd field trip where a bottle of gin or a bottle of vodka has turned out to be very handy!”

“That’s why sometimes we pickle things rather than press them,” Waycott says, before announcing with a great laugh: “You know a really good quality gin can be used for many, many things. There’s the odd field trip where a bottle of gin or a bottle of vodka has turned out to be very handy!”

There’s nothing stronger to fortify this particular quest than a couple of hulking specimen books filled, abstemiously, with dried arrangements. Michelle Waycott looks into one, flips a few pages, and goes back to the soldier’s letter.

She picks up another volume and repeats the process, back and forth between the two a number of times. Then, she puts the eye glass down and settles back in her chair. The big reveal is at hand.

“It looks like a species of anchusa, which is related to the borage family,” she says. “I can’t tell you exactly which species, but it is related to the common anchusa, which is widespread throughout the European lowlands.

“Unfortunately our collection here in Adelaide only has seven species, so I can only compare it to those.”

Borage in bloom at the Adelaide Botanic Garden. Photo: Simon Royal

The flower’s exact name, like that of the soldier who sent it, escapes us. But Michelle Waycott can tell what the man would have seen the day he picked it.

“This group are really well known for their beautiful, bright blue/purple colours, which is why the soldier probably collected it… It would have been a very beautiful flower.

“One of the amazing things about seeing material like this is that it’s looking back in time. That someone, a long ago time, went to a place and chose to pick this or that specimen… it connects us through time.”

July 1, 1916, carries no special meaning for most people – it’s merely another day in the endless row of days past. Professor Robin Prior has a different view, one informed by his lifetime studying the period. The history professor knows instinctively the terrible significance of the date.

“The first of July 1916 was the first day of the battle of the Somme,” Prior says. “It was the most disastrous day in British military history. At the end of the day, for very small amounts of ground gained, the British had lost 20,000 dead and 40,000 wounded, so 60,000 casualties on that day alone.”

The 32nd battalion had only just arrived in that part of France – a piece of luck which saw few of the Dominion soldiers, Canadians and Australians, involved in the Somme.

“If they had been, then we might have been looking at losing our entire national army in a single day,” the history professor says.

On July 1, the Australians would have had little idea of the scale of calamity befalling the British. For that matter, Prior adds, neither did the British High Command. That means Peter’s letter to Vera Rossiter was written in relative peace and quiet.

“I would suggest he [Peter the soldier] was around Armentierès at the time,” Prior says. “This was an area that’s referred to as the nursery section of the Western front.

“I have been there, and it’s gentle, rolling countryside, quite open. So it’s not a bad place, not a bad place to start, if you had to be in the frontline.”

Depending on the division Peter was with, Robin Prior says it’s possible he fought in the battle of Fromelles. Here was yet another day of disaster, where 5000 Australian casualties were recorded. The historian believes the more likely scenario is Peter first saw action at Pozierès in late July, 1916. Either way, in common with every other soldier on the Western Front, Prior says Peter’s days staggered between extremes.

“Battle days were actually pretty rare for any individual unit. There wouldn’t have been many days where you actually went over the top. A lot of their existence on the Western Front was pretty humdrum… carting sandbags, repairing trenches, bringing up stores, and so on. But then you had these battle days, so it was a dichotomy between fairly boring routine activities and then utterly terrifying ones.”

On a torn-off bit of envelope, scrawled in pencil, are the words: ‘Peter the Russian.’

Vera Rossiter was unlike the other young women Peter would have known. His letter home shows this, reflecting her personality as much as his. In the early 20th century, women of Miss Rossiter’s class were expected to be little more than Edwardian ornaments. They decorated the social pages, or their husband’s arm. Vera Rossiter, according to her grandson Michael Gibbs, had other ideas on how to lead her life.

“She was never afraid of voicing her opinion,” Gibbs recalls, smiling at the understatement.

“I’m not sure where it came from, but she had a very strong feminist streak, she was an early feminist… and I think she paved the way for other women to go into business in leadership roles.”

The business Michael Gibbs speaks of is the family firm. The Rossiters were boot-makers, and their brand, Rossi, is still around today. In the 1900s, the Rossiter factory was a major employer around Unley. After she left the Muirden Business College, and barely out of her teens, Vera Rossiter ran the firm’s finances. Her involvement with the company continued until her death in the 1970s.

“I think in those days it helped her voice that she had a big organisation, the family business, behind her,” Michael Gibbs says. “It would have been very hard for a woman otherwise, but she was lucky and privileged to be in her position.”

That position also put Vera Rossiter in the centre of a lively social circle. Company employees, business associates, neighbours, schoolmates – they all worked together, played sport together, went to dances, church dos, and fetes together. When World War 1 broke out, they went into battle together – the men, anyway. Some of them marched off wearing boots they’d help make.

Michael Gibbs with his grandmother’s letters from Europe. Photo courtesy the ABC

Throughout the war years, Vera Rossiter kept up an extraordinary correspondence with these young men. She wrote about how well (or poorly) their rowing and football teams were doing. She wrote about her new car, much to the delight of the men. She wrote saying who was well and who wasn’t, who was married and who wasn’t. In return, the soldiers sent news from the frontlines in Gallipoli and France, or from ships at sea, or on furlough in England. They told her who’d died and how, sometimes graphically.

They wrote with astonishing frankness about the dangers of gas, conscription and the incompetence of British officers. Mostly, though, they wrote how pleased they were to hear from her. One ventured: “I dreamed I kissed you last night.”

Vera Rossiter kept all the letters. Michael Gibbs says over the years about third have been lost, thanks to the usual culprit: a damp cellar. Even so, a couple of hundred letters remain of which Peter’s is one. With it, Vera Rossiter tucked away a clue to the young soldier’s identity. On a torn-off bit of envelope, scrawled in pencil, are the words: “Peter the Russian.”

Peter’s letter to Vera does show signs that English, perhaps, was not his first language. A couple of times he wrote, “has you say”, rather than, “as you say”. But it’s what Peter wrote about, as opposed to how he wrote it, that’s most revealing. Along with all the bright and breezy news from home, one of Vera’s pet topics was to warn the Unley lads off romantic entanglements. It wasn’t that Miss Rossiter minded soldiers sowing wild oats as such, she just didn’t like them landing in foreign places.

“Australian boys should stick to Australian girls,” she scolded one soldier who’d been candid (or foolish) enough to confide he’d fallen for an English “lass”. Peter has no qualms teasing and baiting Vera about her ‘preoccupation’. “We the boys are now here has [sic] you say amongst the pretty French girls to very [unclear] making love… Well soldiers will be soldiers has [sic] you say …but I think they will return for yours…and soon.”

Peter went on to write that the countryside was also “very pretty”, an observation unlikely to have mollified Miss Rossiter. She’d have been mortified to read Peter’s other news: his cousin was on the casualty list.

In fractured terms, Peter then wonders whether someday Vera might “be able” to see his name on the same list. That was the awful reality these young people – friends in peacetime – now shared in war.

Michael Gibbs says his grandmother wanted to hear it all.

“They were clinging on to their relationships, hoping they were going to survive this terrible war. This was her way of supporting them.”

In his letter, Peter wished Vera and her family good health. He asked to be remembered to them all. We don’t know if Peter the Russian came home or whether he’s still in a French field, near where he picked flowers on a summer day. He didn’t select a blood-red poppy or a piece of evergreen rosemary, not that his choice really makes much difference.

One hundred and six summers later, a humble bit of borage has done for Peter the same job as those more celebrated plants of commemoration. Today, we remember him – small blue flowers and all.