State of the state: Looking beyond the budget spin

A close look at jobs growth and other figures in the state budget show the underlying state of the South Australian economy is not as rosy as the Government would have us believe, writes Richard Blandy.

Treasurer Tom Koutsantonis's headline “jobs” measure in the state budget was a $109 million Jobs Accelerator Grant scheme.

The 2016-17 State Budget has some worthwhile initiatives but is disappointing in its expected impact on the South Australian economy.

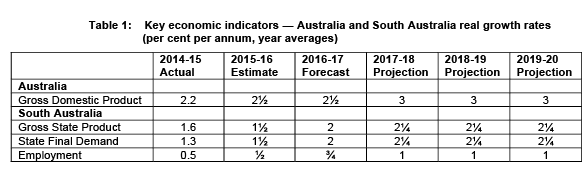

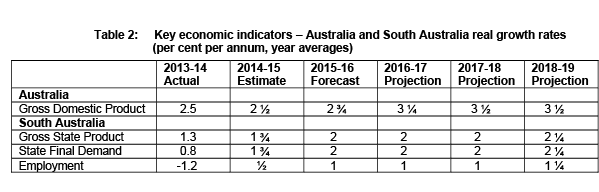

These impacts are presented in Table 1, below, from the Budget Statement (for comparison, Table 2 presents the equivalent table in last year’s budget).

The first thing to notice, comparing these two tables, is that Australian Gross Domestic Product grew more slowly in 2014-15 and in 2015-16 (estimated) than had been expected, and is forecast to grow more slowly in the future than was expected last year. This is not a good sign for our prospects, which are strongly influenced by national movements.

By comparison, although we did not achieve our estimated growth in Gross State Product in 2014-15, and are expected not to achieve our forecast growth in 2015-16, we are now forecast to equal or exceed last year’s projected growth rates by a small margin in 2016-17 and subsequent years.

A similarly slightly more optimistic pattern emerges in the outlooks for State Final Demand, comparing the forecasts and projections for the two budgets.

On the other hand, the outlook for employment, comparing forecasts and projections for each year, are slightly less optimistic now than they were last year.

Give or take, we are not expected to do better in the future than we have been doing, either in output or (especially) employment growth.

This is not the spin that the Treasurer has been running.

Nor is it what one might have expected from the most significant headline measure – the Jobs Accelerator Grant scheme, offering a subsidy of $10,000 for each additional full-time person hired by medium-sized businesses and kept in employment for two years; and $4000 for small businesses that do not pay payroll tax. This scheme is expected to result in an extra 14,000 full-time equivalent jobs.

Given the number of part-time positions likely to be created in the mix, this could well result in 20,000 or more subsidised jobs. Some of these would have been created anyway, so the net number of additional jobs is hard to know – maybe 16,000 over two years – ie equivalent to 8000 extra jobs a year, equivalent to about 1 per cent per annum extra in each of the next two years.

It is curious that this is approximately the same number as the additional jobs expected in total (see Table 1, above). In other words, employment growth is expected to be zero, apart from the jobs subsidised by the Government under the Jobs Accelerator Grant Scheme.

This suggests the expectation must have been that there would be a 1 per cent per annum rise in unemployment over the next two years without this scheme, notwithstanding the employment effects on the beleaguered construction sector of the $500 million “science labs for schools” scheme also announced in the budget, as well as a continuation of other very significant infrastructure spending. Remember, this period takes in the closure of the Holden factory at Elizabeth.

The underlying state of the South Australian economy – as implied by the Government’s own budget measures – is therefore disastrous.

A healthy South Australian economy would have jobs growth of double the rate being forecast and a GSP growth rate of double the rate estimated for 2015-16.

What the wage subsidy scheme shows is that the State Government recognises that wage rates matter in terms of job creation, and that wage rates are too high in South Australia to allow enough jobs to be created to stop unemployment rising. The ceiling on public service pay rate increases also recognises this.

The Government should be arguing at Fair Work Australia that its cap on wage increases should be allowed to apply to all businesses in South Australia under its jurisdiction until the unemployment rate in the state falls to the national rate.

South Australian businesses must be allowed by the State Government to make greater profits. Why? So that they will invest in expanding their businesses and employ more people as a result.

Competition will ensure that the rates of profit that they make are fair and moderate. To achieve this, the South Australian Government must reduce state taxes and the impact of state regulations on the incentive for businesses to invest in South Australia. The Government must also cut its own spending (lower taxes will be seen to be temporary if spending is not cut, because otherwise, the deficit will increase and higher taxes can be expected in the future).

The budget has some interesting information on tax “effort” by each state and territory (Table 3.13: Tax effort ratios by jurisdiction, page 44 of the Budget Statement). These tax effort ratios are compiled by the Commonwealth Grants Commission as part of the process of dividing up the GST revenue among the states and territories. States that have high effort ratios are entitled to higher GST transfers than states that do not.

In 2014-15, South Australia was assessed by the Commission as having made the highest tax effort of all the states and territories. In other words, our state taxes are higher (relative to our wealth, income and so on) than anywhere else in Australia. This is one reason why we get so much of the GST revenue that Canberra collects for the states and territories.

The State Government also publishes in Table 3.13 a set of “adjusted” ratios, taking account of differential land tax rates among the states and territories. By this reckoning, South Australia’s tax effort falls in the middle of the pack.

Hence, we can conclude that the South Australian Government does impose a very high tax burden on SA citizens and businesses, notwithstanding its claims to the contrary.

The budget also claims to have made a surplus of $258 million in 2015-16. However, the surplus results from a so-called “special dividend” of $403 million from the sale of the Motor Accident Commission for $1.6 billion. The $403 million is a capital item, not a current revenue item. Without that consumption of capital, the claimed surplus becomes a deficit of nearly $150 million. This is a recurring theme.

The State Government continues to sell assets to fund recurrent spending. This is what people who are broke do.

Finally, the 2016-17 and subsequent budgets show big increases in grants from the Commonwealth, particularly in GST revenue grants, specific purpose grants and capital grants, raising total grant revenue by 10 per cent (more than $1 billion in 2016-17 and subsequent years). It is not only in being awarded the submarine contract that we are substantial beneficiaries of Commonwealth Government largesse.

Richard Blandy is an Adjunct Professor of Economics in the Business School at the University of South Australia and a weekly contributor to InDaily.