The 70-year-old mystery about the fate of an Adelaide pilot – shot down near Berlin in 1943 – has been solved in extraordinary fashion.

Last year, a lost World War Two bomber was discovered in a German forest, sparking an international search that has now made its way to Adelaide.

The Royal Air Force Lancaster bomber’s crew of seven included four Australians, including young pilot Flight Sergeant Robert Naffin, a 23-year-old from North Adelaide.

Remarkably, not only the wreck of the plane has been positively identified but an eye-witness to the bomber’s last moments has also been discovered.

For all of his life, Bob Naffin, 69, knew little of the World War Two bomber pilot after whom he was named.

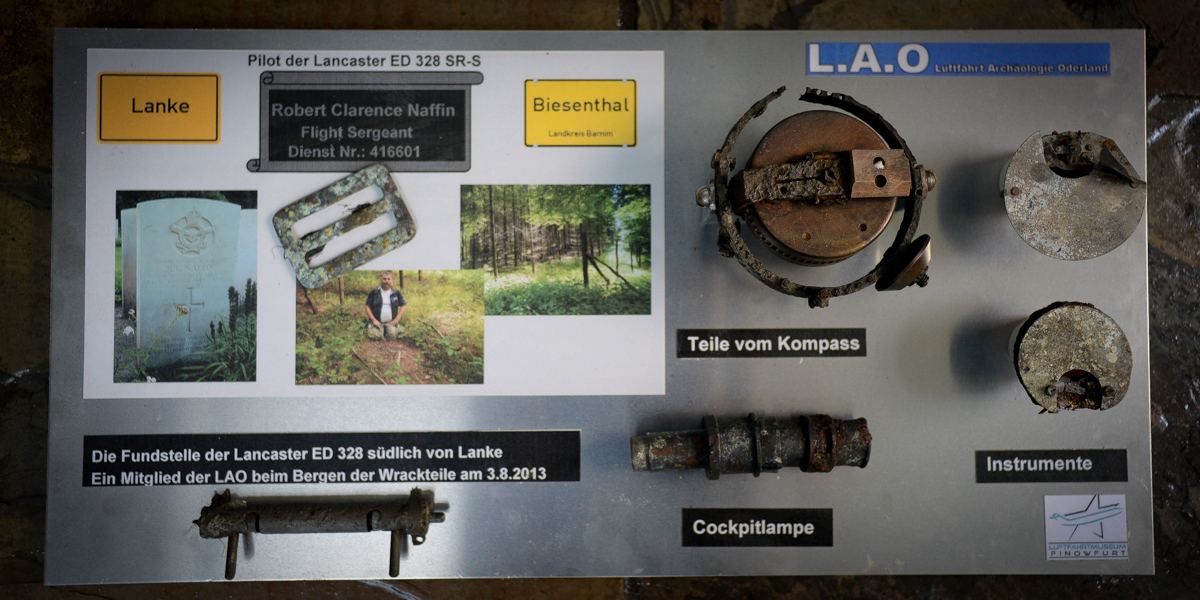

Today, he sits in his Vale Park home touching, looking and connecting with the fragments of Lancaster ED 328, the Bomber Command plane that German aeronautical historians discovered in a German forest last August.

Bob was named after his uncle, killed on his 13th mission when his plane was shot down on the night of 23 August 1943 after a bombing run on Berlin.

An international cooperative effort involving volunteers from Germany, the United Kingdom and Australia has delivered parts of the plane’s wreckage to Adelaide – along with witness reports of the plane and crews final moments.

It has brought a war hero to life.

“This makes him so real to us,” Bob, a retired public servant, told InDaily.

“You feel part of him is here.

“We now know who he was, what he did, about his wife and the daughter born just four months before he died.

“We’ve connected with people in the UK and in Australia – we have a common bond of loss.

“This has had a profound impact on our family.”

A small band of German historians answered a plea in early 2013 from Welsh businessman Ian Hill, a nephew of one of the crew of ED 328.

They tracked down the plane’s fate, found a witness to the mid-air encounter with the Luftwaffe’s Major Werner Hussman and gathered pieces from the wreckage of the downed Lancaster, deep in a forest 15 miles from Berlin near a town called Lanke.

In another twist, the historians discovered Hussman – who was awarded the Iron Cross by Adolf Hitler – was still alive and living in a retirement home nearby.

He died two weeks ago, aged 94.

Along with Ian Hill, the historians started the long process of tracing relatives of the seven crew and compiled a book that detailed the discovery of ED328.

Four of the crew: Sgt. John Phillips; Fl Sgt. Douglas Tresidder; Fl Sgt. Robert Naffin; and Sgt. David Morgan Ellis

“We historians of the aviation museum Finowfurt found out that even 68 years after this terrible war people still look for their relatives,” their spokesman Christian Wengel wrote.

“There are many reasons for that – some want to visit the grave of their relatives – others want to know how their relative died or even don’t know where their father or children ended up in the chaos of war.

“We want to make a little contribution.

“Someone eventually dies, when people stop talking about him/her.”

Bob Naffin had given little thought to the circumstances in which his father’s brother had come to such a tragic end at age 23.

“It wasn’t talked about much – just that he died in the war – that he was buried in a war cemetery in Berlin. That was all.”

A phone call in November last year changed all that.

The 1939-45 Berlin War Cemetery where the Australians are buried

What would evolve in the ensuing weeks would be a fascinating tale of bravery, love lost and the honourable response from a nation that was our wartime enemy.

Robert Naffin was born in North Adelaide in 1920, one of two sons (Glenn, Bob’s dad, was the other).

He enlisted in the RAAF in July 1941 just after he turned 21.

Like many Australian airmen, he quickly found himself in joint operations out of England under the banner of the Royal Air Force’s Bomber Command.

In the period 1940 to 1945 RAF Bomber Command attacked German targets east of the Rhine, destroying much of Nazi Germany’s industries.

The raids caused the loss of up to 600,000 civilian lives.

The toll on Bomber Command crews was massive.

It would lose 47,628 crew – 8209 were Canadians, 3412 Australians and 1433 from New Zealand.

By 1943, aircrews had just a one in four chance of surviving their first 30 missions.

In August 1943 Bomber Command’s target was the infamous Peenemünde V-2 rocket facility.

The V-2 was a long range weapon that threatened to turn the war the way of the Germans.

The extent of this air war is shown in the notes on one of Naffin’s unit’s files:

“COLOGNE: 28/29 June 1943. 608 aircraft left to attack this city. Cologne suffered its worst raid of the war; 43 industrial 6 military and 6368 other buildings were destroyed and nearly 15,000 others damaged. 4377 people were killed, 10,000 injured and 230,000 forced to leave their damaged homes. Robert and his crew took ED320, took off at 2325 and returned at 0425. 25 Aircraft were lost; none from 101 squadron.”

On the night of August 23 the seven man crew of Lancaster ED 328 was made up of three British airmen of the RAF and four Australian members of the RAAF. Naffin was the pilot – it was crew’s 15th mission and Robert’s 19th.

Nearby at their base home, Naffin’s new wife, Diana, and four month old daughter Bonny.

Naffin guided his Lancaster down the runway at 20.27 hrs on 23 August from Lincolnshire, heading to Berlin as part of a force of 727 aircraft consisting of 335 Lancasters, 251 Halifaxes, 124 Stirlings and 17 Mosquitoes.

It would be the largest day and night of bombing during the period: 727 went out – 671 returned – the greatest loss of aircraft in one night.

Official records show that Robert Naffin’s plane was lost trying to return to the 101 Squadron base in Lincolnshire.

The RAF crash report during the war couldn’t pinpoint where the Lancaster came down.

In November 1943, Robert’s family received an official letter from the RAAF, notifying them that their son was “reported missing as a result of air operations on the night of 23rd August 1943”.

The letter also reported that a member of the crew is “believed to have lost his life”.

It cited information from the International Red Cross that “according to German information, this member lost his life on the 24th August”.

“No further information of your son is available but … any further information received will be conveyed to you immediately.”

Back in Australia, the RAAF personnel file notes show that the family made further contact with officials in 1946 seeking more information.

An investigation was conducted by the RAAF Missing Research and Inquiry Unit. It concluded that the aircraft had crashed two kilometres south of Lanke, near Berlin and all seven men had perished.

Remarkably, the crew had been buried by the locals with full military honours.

“Herr Kunne and Herr Kloss, the gravediggers, assured me that the bodies had been given a proper funeral,” the report’s author wrote.

“Superintendent Jaeger of the Evangelical Church held a service at the grave, after which a Luftwaffe detachment of eight men fired a volley.”

The Allied Forces investigation team exhumed the bodies.

“Grave 1091 contained the body of F/Sgt Naffin as he was wearing a dark blue battle dress,” the report said.

The RAAF moved the bodies of all seven crew to the official 1939-45 War Cemetery in Berlin where they remain today.

That year, the families were notified of their location.

“That was all we knew really,” Bob Naffin recalls.

“It wasn’t talked about much.

“My grandparents, however, had a metal name made for their house in Myrtle Bank – it was ‘Trebor’ – which is Robert backwards.”

When Bob’s grandmother passed away, he took the name off the house and it’s now bolted to his family home in Vale Park.

That would be his only tangible memory of the man his father named him after – until November 2013.

One of the Lancaster crew – Sgt John Phillips – had left behind a sister, Alwyn. She had grieved for her brother for decades.

Last year, her son, Ian Hill, decided to seek some form of closure for his then 81-year-old mother and he posted requests on the internet for information.

One of the posts was seen by the historians from Luftfarhrt Archaologie Oderland (LAO).

In January 2013 they began a search for ED328.

They started with the coordinates from the 1946 investigation, but “unfortunately the search was not successful. These coordinates have been a riddle to this day,” Christian Wengel wrote.

They searched an area called Lake Hell – again with no success.

“Quickly we notice that we won’t be successful with a conventional search,” Wengel wrote.

“We have to find contemporary witnesses to get a result.”

They arranged a meeting with local historian, a Mrs Gertrud Poppe.

She knew the names of the two gravediggers, but they had since passed away, as had the Pastor who had officiated at the burial.

Then, a breakthrough.

Another local pointed them to two books by a Dr Hans Richter – Episodes from Lobetal and Codename Koralle – that included military reports and the graphic recollection of an air crash.

Hans Richter was still alive and Wengel’s men sought him out.

Richter’s book had included the diary notes of a radio operator, Petty Officer Waldemar Steinmuller, stationed near Lanke:

“11.45pm Air raid warning. Major offensive in Berlin. It is a night with bright moon. The offensive happens in 5 to 6 waves, more than 300 machines? You can’t hear the single machines any more, just a single loud humming. The flak is shooting a bit, because about 200 German night fighters are in the air. As soon as they identify an aggressive bomber, 2 to 3 night fighters start to attack it. Clearly you can see the burst of fire of the tracer bullets. Already after a few moments the struck hostile bomber is flaming up, then is ablazing till it eventually is spinning down vertically with a fiery tail breaking apart at the same time and crashing. Everywhere you can see them crashing down like burning torches. One plane crashes just next to us. For a moment the sky is bright red on the crashing site. On the edge of the forest next to the road there is a part of a wing lying, an engine. Next to it a charred body without head and legs, just stumps. The fire brigade is extinguishing the fire and is closing off the area. On the next morning we find more plane debris in a radius of about 1 km; also two more charred bodies and an unhurt one. It is the body of a 23 years old Australian. In the pocket of his uniform there is a piece of paper with the request to the commander, to be allowed to come to the next deployment. This note was from August 22nd. On August 22nd he had his will and now he is dead.”

When Wengel met with Dr Richter, he discovered that the then-14 year old Richter had also witnessed the crash of a Lancaster that night in 1943.

It had been shot down by decorated German pilot Major Werner Husseman.

The next day, locals had found five charred bodies and a crew member (Flt/Sgt Phillips) leaning on a tree.

Phillips had been able to parachute from the plane, but he died later on site.

Richter, 70 years later, would lead Wengel and Ian Hill to the same site.

Richter (left) with Ian Hill (rear) and F/Sgt Phillips’ sister Alwyn

“He was just a 14-year-old schoolboy at the time but he is still living in the area and guided us to where the plane came down in dense forest,” Hill told InDaily.

“He said the Lancaster was attacked from underneath and its fuel tanks were hit – causing it to explode in mid-air.

“His memory is so vivid. It was an extremely traumatic experience as it took place over his head.

“He said he saw a chain of light going from the German night fighter to a large black four-engined plane.

“Next there were sparks and a huge red fireball and then the plane came down in parts after exploding.

“His father was the head of the local fire brigade which had to tend to the crash site and exhumed the bodies.

“It was wonderful to learn they were laid out in the village hall and buried in the local cemetery with full military honours by the Luftwaffe and treated with respect.”

On August 3, searchers found parts of the cockpit of Lancaster ED 328 and hundreds of parts spread on the floor of the forest.

A 70-year-old mystery had been solved.

Each part was collected and later catalogued and identified.

Hill then began the search for relatives of the other six crew members.

In Vale Park, last November, Bob Naffin’s phone rang.

“They wanted to know if I was related to Robert Naffin,” Bob recalls.

“We had already had contact two years ago from some of Robert’s descendants in the UK, but they knew as little as we did of what had happened that night in Germany.

“We have been on a roller coaster of emotions as the reality of this tale has unfolded.

“Robert Naffin, the wartime pilot, has come alive in our memories.

“I’ve been awestruck – after 71 years, I feel part of him is here.”

During one of the conversations with the searchers, mention was made that they would send an artefact to Bob.

Several weeks later a large parcel arrived – inside was two mounted collections of parts of the wreckage, most from inside Robert’s cockpit.

*Image by Nat Rogers

The compass still swivels.

Bob moves it back and forth slightly – just as his uncle had done 71 years ago.

The sense of contact is irresistible.

“His daughter Bonny was born a few months before the plane went down,” Bob says.

“She died herself in 1963.”

Bonny’s step sister Dee Kennedy and husband Joe Kennedy will soon be coming to South Australia.

She’ll be able to pick Bob’s house – it has a name on the front; “Trebor”.

Bob Naffin. Image by Nat Rogers. The Lancaster parts display will be donated to the Aviation Museum at Port Adelaide.