Wine’s place in the luxury goods market

Whitey ponders the international slump in luxury goods sales, and how it relates to aspiring premium wine producers.

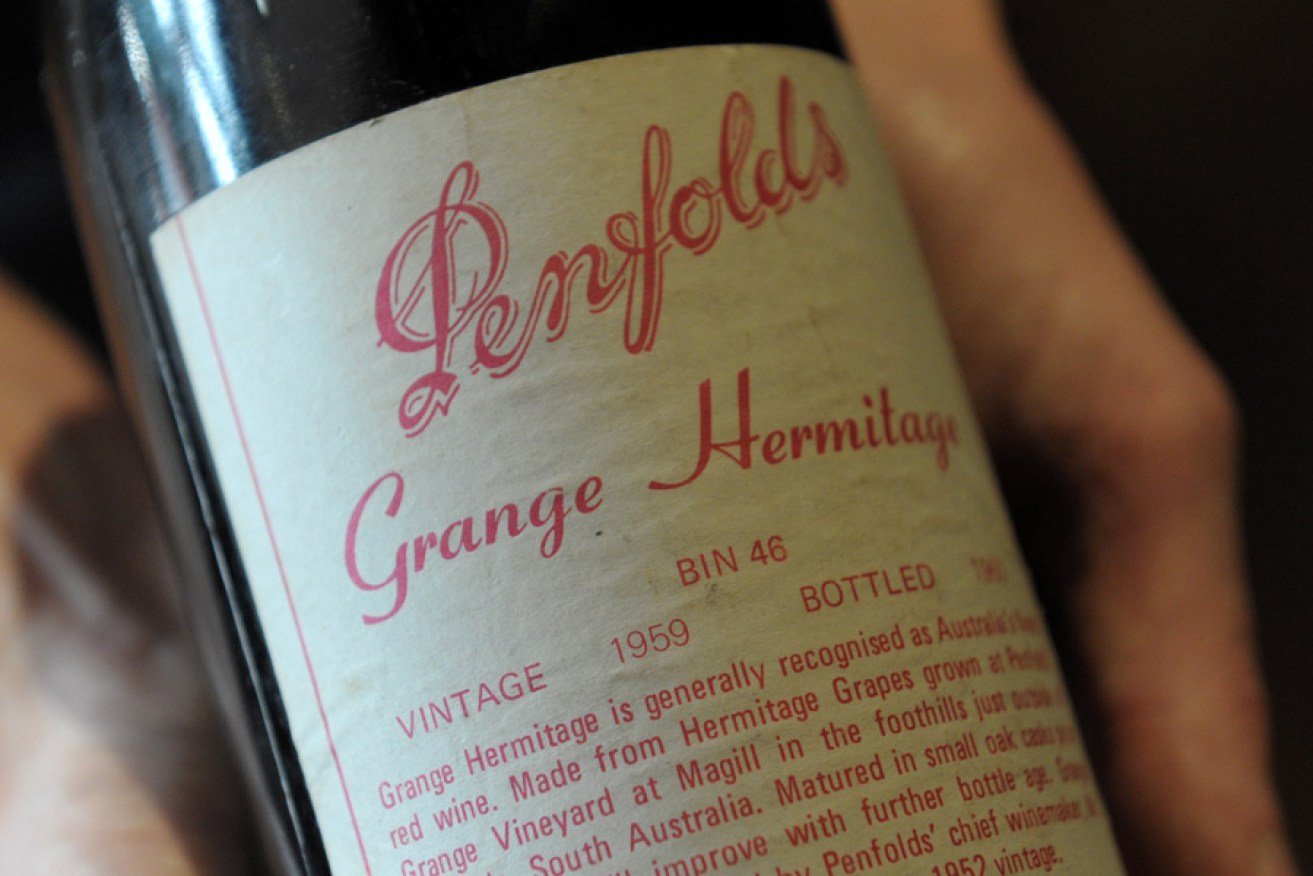

Pure luxury: A bottle of 1959 Penfolds Grange. Photo: AAP

“Ideology: the mistaken belief that your beliefs are neither beliefs nor mistaken.” So says Eric Jarosinski, the New York-based editor of the “the internet’s Compendium of Utopian Negation”, the Nein Quarterly, which seems mainly composed of brilliantly witty tweets.

And Jarosinski’s lecture tours.

Australia borrows a lot of its English from the United States, which borrowed it from Britain, Africa and Europe. Even Germany. Grovelling to American wine buyers like the sly Dan Philips in the mid ’90s led some of us to adopt a word he thought was kinda cute: artisanal.

Suddenly we had artisanal winemakers. And then we had the Young Artisans. And then Philips and his Grateful Palate exercise vanished back into the US, leaving millions of dollars of debt and a herd of terrified artisanal winemakers who suddenly faced life without the support of the US critic Robert Parker Jr, to whom Philips had been the conduit.

The adherents to this tetchy artisanal uprising really did seem mistakenly to believe that their beliefs were neither beliefs nor mistaken.

Being philosophically more of the Nein than artisanal school, it was with a certain glee, about a decade back, that I greeted the news from Barossa winemakers Charlie Melton, Big Bob McLean and Peter Scholz, that they would henceforth be called The Old Fartisans as they drove around together drinking beer and delivering wine from the back of a huge Nissan four-wheeler. More than anywhere else, I seemed to find them in the Mallala pub, which was about as far from the Barossa as that particular export drive extended.

I write so loudly on this as I was always of the perhaps mistaken belief that an artisan was an artificer, someone who spent their lives mass-producing copies of great artworks and fitments that their customers could never afford in the orginal version. Like, for example, the dude with the plaster works, turning out thousands of metre-high copies of Michelangelo’s David, all sharing the deformities inherent in the crafter’s imperfect mould.

The artisanal appellation seems to have mercifully waned with the memory of Philips. It was first replaced by the light-hearted ridicule of the Old Fartisans, for which there’s no longer much call since the death of Big Bob and the consequent return of Scholz and Melton to their vineyards and vintage sheds.

But all this left me with an abiding suspicion that most artisans were indeed true to their banner. As a mob, they seemed intent on reproducing endless imperfect copies of much more famous wines that they couldn’t afford to drink, and their customers could never afford to buy. If, just for example, you were engaged, however deliberately, in copying the style of Penfolds Grange, there was always the nice little incentive there called potential margin.

Even Treasury Wine Estates fully understands this. Bin 389 is “the baby Grange”.

Like, if one couldn’t stretch one’s skill set to the extent of, say, coming up with a new style or idea, and instead just stuck to emulating a Grange one once tasted, one could jack up one’s price quite a distance past the $20-$25 bracket, especially if Dan Philips rang to say Parker had just awarded one the perfect 100-point score.

Herein lies the difference between what I consider to be “premium” wines – not my term – and “luxury” ones.

Like with its pricing, unique provenance, incredible mystery and what the “Amurkhans” who’ve forgotten the meaning of “history” call “back story”, Grange is luxury. Pure and simple. It’s an original. It’s unique.

While his sales figures still soar, my friend Peter Gago, chief winemaker at Penfolds, easily Treasury Wine Estates’ biggest buck bang per bottle, is a tad more coy about the international luxury goods market.

Things out there ain’t quite such the easy breeze they have been in recent years, especially in luxuries other than very fine wine.

Not only is social media democratising the luxury goods landscape, spoiling its exclusivity for the truly loaded elites, but the terrorism business has put an end to a lot of impulsive first-class travel, the sales of really posh extravagances has dwindled, and China’s top-end spend has tumbled all the way across handbags, shoes and malt whisky to Bordeaux and Burgundy. Et cetera.

As if to convince the freshly parsimonious mega-rich that everything’s tickety-boo, many of the manufacturers of top-end caucasian artefacts have increased the dividends they pay their shareholders, a move which is raising increasing derision in the markets: the pundits are saying this can’t possibly go on.

Which brings me to another New York-based outfit, Milton Pedraza’s Luxury Institute, and its recent white paper, 7 Rule-Breaking Moves Needed Now to Flourish in the Most Perplexing Luxury and Retail Market Ever.

Pedraza quotes Warren Buffet:

Be fearful when others are greedy, and greedy when others are fearful.

He suggests that while further automation, more robots and digitisation is inevitable and partly necessary at the production end, these mechanisms “are all commodities that create zero competitive advantage …”.

“Playing defence in this highly complex downturn, where store traffic and sales can be down as much as 20 per cent, will further weaken brands.”

The Luxury Institute doesn’t report much on the top end of the wine market, but I have always found it a handy measure of the shorter-term future of expensive wine internationally.

Like at Louis Vuitton Moet-Hennessy, Dom sales follow handbags.

In the face of today’s downturn, Pedraza says “the reaction from most luxury and retail brands has been to shut stores, cut people, cut costs and dive deep into the trenches until the crisis passes”.

This, he says, is wrong. Tellingly, he urges a major rethink across the sector, and his advice is just as good for artisans as it is for the luxury brands they artifice.

While he never dares suggest tootling about drinking beer in a big 4WD to make personal deliveries, that’s pretty much along the lines of his solution. It’s all about people, and better, more polished and reliable personal service. Don’t simply close stores, he suggests, but train your sales folks better. Retain them; slow your staff turnover. Make them happier to stay. Encourage the best of them. Reward those who offer constant, truthful, reliable attention to long-term customers: believers in the brand. Slash your numbers in head office, not the troops out on the front.

In previous reports, the Luxury Institute has repeatedly warned that there’s no point in having websites and digital mailouts unless they’re kept up-to-date and the prospective client can phone a real human with a real name on a real phone number listed right there.

Repeatedly. Reliably. Intimately.

All this conveniently applies as much to the artificers as the very big companies with luxury goods. In fact, it would be wise for more of the aspirant little guys to learn conversely from the leviathans: grow and reward your front-line troops rather than stacking head office with psychopaths in suits.

And never decry Peter Gago’s tireless regime of travelling the world every minute of every day you’re not at home touring vineyards, making new wine or blending maturing batches. Be personal and absolutely reliable; tell the truth.

This may all seem pretty obvious, but there’s little point in being fearful when others are greedy, and greedy when others are fearful if your ideology involves the mistaken belief that your beliefs are neither beliefs nor mistaken.