Dunstan bio promises the whole story

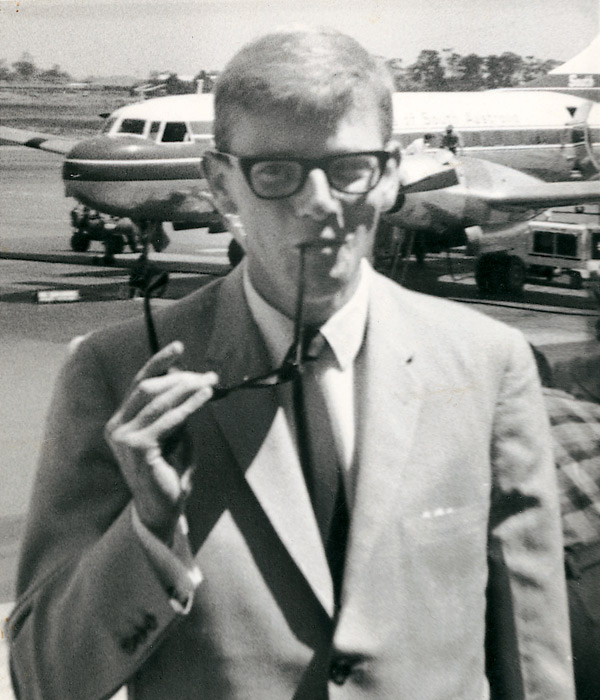

Dunstan family portrait by Colin Ballantyne, c1957. Courtesy Bronwen Dohnt.

A new biography which promises to reveal more about Don Dunstan than has ever been known before will be officially launched at the Norwood Town Hall tonight.

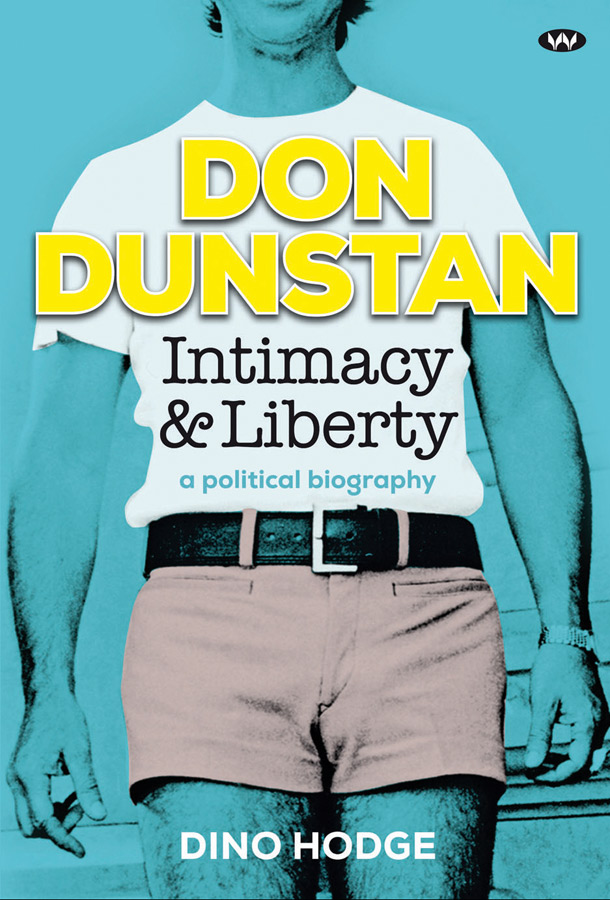

Don Dunstan: Intimacy & Liberty, by Dino Hodge, examines the former South Australian premier’s personal and public life and relationships in the context of the social and political issues that dominated the era.

Hodge, a former ministerial adviser in Canberra and author of two oral history books on Darwin’s multi-cultural gay community and the spiritual beliefs of gay men and women, devotes the early chapters of his book to painting a picture of what life was like for homosexuals in South Australia in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s. The middle section concentrates on Dunstan’s time in power (particularly his human rights record), while the last third explores “the private Don”.

The following extract, printed with the permission of the author and publisher Wakefield Press, is from a chapter headed Loves Found and Lost.

Ermyntrude and Esmerelda

The small ‘l’ liberal philosophy inspiring Dunstan in his political life similarly inspired him in his personal life. One of the British rationalist philosophers admired by Dunstan and [first wife] Gretel held the view that some human relationships were primary while others were secondary. They were familiar, as well, with the heterosexual-homosexual behavioural rating scale published by Alfred Kinsey in 1948. It placed only a few people as either exclusively heterosexual and homosexual, with most somewhere in between and having sexual experiences with both men and women. A favourite work of theirs, especially for Gretel, was the illustrated edition of Ermyntrude and Esmerelda by Lytton Strachey, a humorous yet sardonic exposure of Victorian attitudes to sex and sexuality as recorded in the correspondence between two young women. The heroines uncover the purpose and manners of ‘pussies’ and ‘bow-wows’ through an array of romantic and physical entanglements – both theirs and those of others – crossing gender, class and age.

Dunstan was a gifted pianist and would always have a piano in the home which doubled as his electorate office until the ALP won government.

By the early 1960s, Dunstan was helping the ALP with its campaigns in other Australian states. It was during one of his interstate trips that he met a school teacher actively involved with the Party. Dunstan took a special liking to the young man and invited him to help out in a South Australian campaign, offering accommodation in the Dunstan household. This visit was repeated on other occasions, and eventually the Dunstan children took to referring to their visitor as uncle. During one of these stays, Dunstan needed to attend a national ALP committee meeting interstate and, upon his return home, was distressed to learn of Gretel’s relationship with the young man. Over the years that Peter Ward was employed by Dunstan, he learnt many details about their personal lives, and he came to understand that Dunstan and Gretel each enjoyed secondary relationships during the 1960s but, on occasion, found annoyance in the other’s behaviour.

Dunstan told Ward that he needed special friendships in his office, ‘uncritical male confidants whom he could trust absolutely, if his life’s work as a visionary leader of a Labor-governed polity was to be properly achieved’. One of the earliest such relationships was with Gerry Crease, whom Dunstan first met during the 1962 state election campaign and who later joined Dunstan’s staff in the mid-1960s. Ward describes Crease as ‘an erratic, flamboyant and sometimes eccentric bi-polar enthusiast’. He further recounts an incident during the crisis in 1967 over the appointment of John Bray as Chief Justice. It was late afternoon on a Friday that Bray met with Ward and told him of the attempt by Police Commissioner McKinna to block his appointment. McKinna alleged that Bray was homosexual, but Bray mistakenly believed instead that the issue was that he had been linked with a homosexual. Bray supposed this to be Ward and raised the issue with him, warning that it was possible that Ward and his partner, Dimitri Theodoratos, might be raided by the police and interrogated. Ward immediately went to Dunstan’s home to discuss the problem:

His house was in an uproar. The phones–the listed and unlisted lines–were ringing constantly. Gerry Crease met me, shook my hand, and welcomed me to ‘the club’, saying ‘they’ve been saying it about me for years’– I took him to mean ‘homosexual’.

Crease was, explain Neal Blewett and Dean Jaensch in their book describing the 1960s transition from conservative to progressive government in South Australia, ‘the most independent and imaginative, if also the most abrasive, personality’ in the Dunstan team. He had been employed by the advertising agency used by the ALP, and in 1962 he worked on the first full-scale television campaign that Labor had run. He understood Dunstan’s concern that the advertisements should target the inadequacies of the Playford Government’s record in health, education and welfare services. When Playford was replaced by Walsh in 1965, the latter asked Crease to join his staff. A public relations officer position was created in the Premier’s Department and Crease was appointed. Unsurprisingly, their working relationship was fraught and, when Walsh wanted to sack Crease, Dunstan arranged for him to be transferred to his own Department. Dunstan recalled:

Gerry became aggressive at incompetence or humbug, was no respecter of persons, dressed scruffily and carelessly, kept irregular hours, was enormously widely read and informed and contemptuous of those who weren’t, was the enemy of formality, constantly perpetrated practical jokes, particularly against the pompous. One had to be careful how one expressed oneself in front of him, as he was quite capable of deliberately taking you the wrong way. (I have known him go into a restaurant, see a sign ‘Toss Salads at the Bar’ and pick up the salad vegetables and pelt them at the bar.)

Crease’s erratic behaviour could at times create difficulties, but Dunstan found much of his work to be highly valuable, and he credits him for contributions such as innovations in the use of the media cycle to maximise exposure. It was Crease who nominated Bob ‘Bobbing and Ducking’ Bakewell for appointment as a Public Service Commissioner. When Adelaide’s water supply was threatened by drought in the summer of 1967, Crease devised a campaign in which school children were encouraged to form ‘water-watcher’ clubs that were awarded prizes; the impact of these voluntary wardens saw water consumption decrease by more than ten per cent, eliminating the need for the imposition of water restrictions.

Gerry Crease, Dunstan’s adviser during the mid-late 1960s, moved into the Dunstan family home and entertained the Dunstan children.

It was during this period that Crease joined the Dunstan household. Gretel was continuing to help with the political workload and had started work at the University of Adelaide tutoring in economics. There was a frequent need for baby-sitting the three children, and Crease had a need for somewhere to live other than sharing with his mother in a flat where he could not keep a dog. So Crease moved in with Dunstan and Gretel, keeping the family entertained with his antics. Rumours began to circulate about the men. Ward at that time was employed at 5KA, the radio station where Dunstan would record his weekly broadcast on behalf of the ALP, and recounts that ‘there was some snide nudging and winking among the broadcast staff of 5KA, especially when Dunstan turned up with Gerry’. The journalist Mark Day, then working as a political reporter for the News, had an arrangement whereby Dunstan and Crease would visit him on the weekend at his home to brief him with news for the Monday edition. Day had heard the repeated rumours about Dunstan’s homosexuality but had not given these much thought until an incident one weekend:

Gerry was in a, I would describe, an ebullient frame of mind … They came in and they sat … on a sofa – and they were pawing each other. Gerry was all over him! Don was kind of fending him off, but in a jocular way. And it just struck me that they were … highly intimate.

Extract from Chapter 7, Loves Found and Lost, Don Dunstan: Intimacy & Liberty, by Dino Hodge, published by Wakefield Press, $39.95. The book will be launched tonight (Thursday) by Catherine Branson QC at a gala event at the Norwood Town Hall.